As the presidential campaign slowly progresses, artificial intelligence continues to accelerate at a breathless pace — capable of creating an infinite number of fraudulent images that are hard to detect and easy to believe.

Experts warn that by November voters will have witnessed counterfeit photos and videos of candidates enacting one scenario after another, with reality wrecked and the truth nearly unknowable.

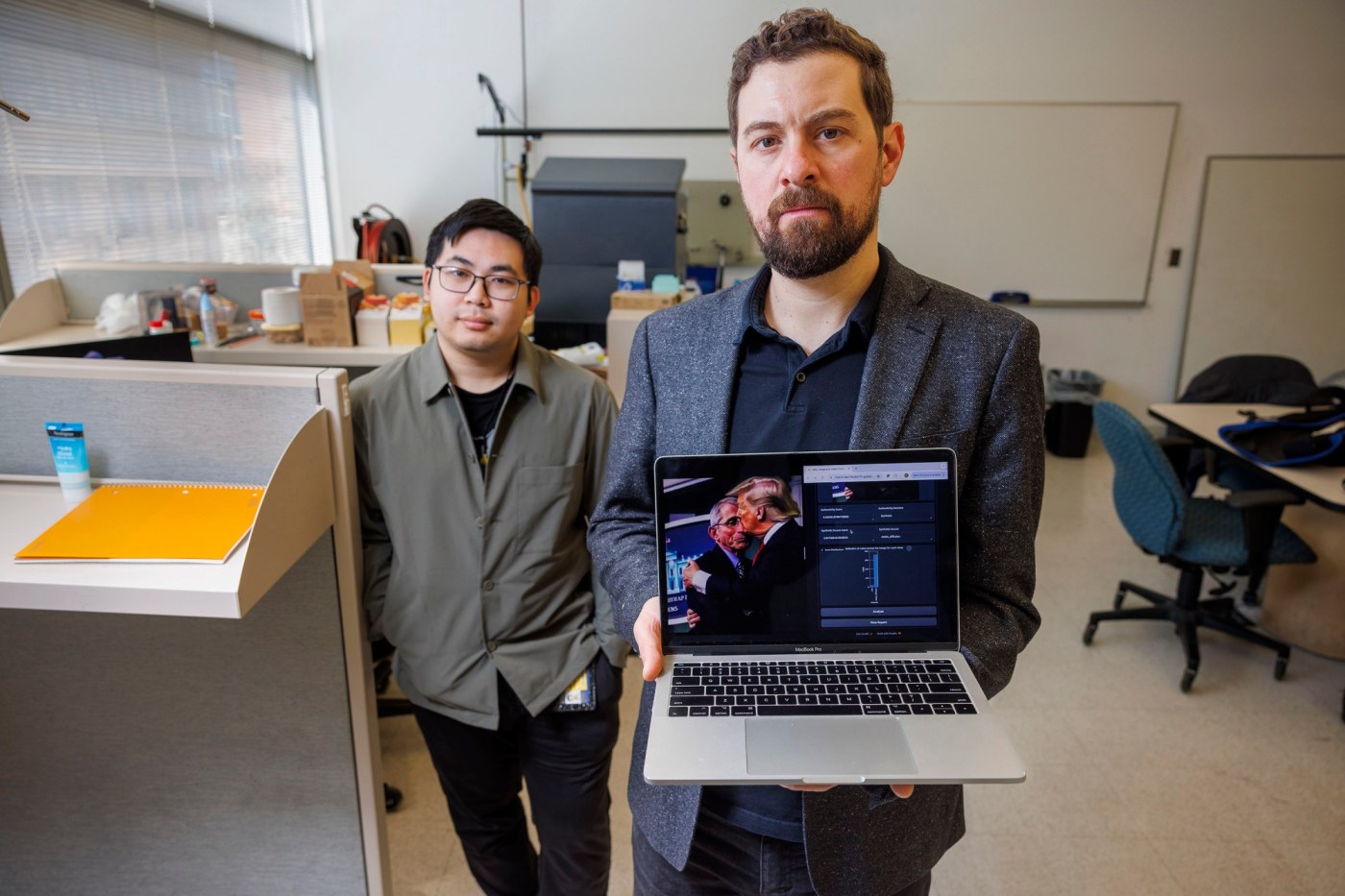

“This is the first presidential campaign of the AI era,” said Matthew Stamm, a Drexel University electrical and computer engineering professor who leads a team that detects false or manipulated political images. “I believe things are only going to get worse.”

Last year, Stamm’s group debunked a political ad for then-presidential candidate Florida Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis ad that appeared on Twitter. It showed former President Donald Trump embracing and kissing Anthony Fauci, long a target of the right for his response to COVID-19.

That spot was a “watershed moment” in U.S. politics, said Stamm, director of his school’s Multimedia and Information Security Lab. “Using AI-created media in a misleading manner had never been seen before in an ad for a major presidential candidate,” he said.

“This showed us how there’s so much potential for AI to create voting misinformation. It could get crazy.”

Election experts speak with dread of AI’s potential to wreak havoc on the election: false “evidence” of candidate misconduct; sham videos of election workers destroying ballots or preventing people from voting; phony emails that direct voters to go to the wrong polling locations; ginned-up texts sending bogus instructions to election officials that create mass confusion.

Pennsylvania Secretary of State Al Schmidt is leading a newly formed Election Threats Task Force, intended in part to combat misinformation about voting. In a brief interview, Schmidt noted that in recent years we’ve seen “how easily misinformation has been spread using far more primitive methods than AI — tweets and Facebook posts with no video or audio.

“So AI presents a far greater challenge if it’s weaponized to deceive voters or harm candidates.”

Sham Biden call

Like the internet itself, AI can be a powerful tool to both advance and hinder society.

And while bad actors have long possessed the ability to generate fraudulent content in the digital age, the contouring of text and imagery to shame or denigrate a political opponent was once “slow and painful,” said computer science professor David Doermann from the University of Buffalo, State University of New York.

“It took work to use Photoshop and video tools,” Doermann said. “You needed experts. But now, your average high school student can generate deepfakes.”

Deepfakes are synthetic media in which a person in a photo or video is swapped with another person’s likeness, or a person appears to be doing or saying something they didn’t do or say.

A recent example occurred before the January New Hampshire primary. An AI-generated robocall simulated President Joe Biden’s voice, urging voters not to participate, and “save” their votes for the November election.

Average voters could have easily believed Biden recorded the message and become disenfranchised as a result, noted the Campaign Legal Center, a nonpartisan government watchdog group in Washington, D.C.

“This is the first year to feature AI’s widespread influence before, during and after voters cast ballots,” said CLC executive director Adav Noti. “AI provides easy access to new tools to harm our democracy more effectively.”

Malicious intent

AI allows people with malicious intent to work with great speed and sophistication at low cost, according to the Cybersecurity & Infrastructure Security Agency, part of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security.

That swiftness was on display in June 2018. Doermann’s University of Buffalo colleague, Siwei Lyu, presented a paper that demonstrated how AI-generated deepfake videos could be detected because no one was blinking their eyes; the faces had been transferred from still photos.

Within three weeks, AI-equipped fraudsters stopped creating deepfakes based on photos and began culling from videos in which people blinked naturally, Doermann said, adding, “Every time we publish a solution for detecting AI, somebody gets around it quickly.”

Six years later, with AI that much more developed, “it’s gained remarkable capacities that improve daily,” said political communications expert Kathleen Hall Jamieson, director of the University of Pennsylvania’s Annenberg Public Policy Center. “Anything we can say now about AI will change in two weeks. Increasingly, that means deepfakes won’t be easily detected.

“We should be suspicious of everything we see.”

‘Democracy can wither’

Misinformation has gushed like a “fire hose of falsehoods,” some of it from Russia, said Matt Jordan, director of the Pennsylvania State University News Literacy Initiative, which helps students and citizens distinguish “reliable journalism” from “the noise that often overwhelms and divides us,” according to its website.

Democracy, Jordan said, “depends on a capacity to share reality,” which misinformation shatters. In such an atmosphere, he warned, “democracy can wither.”

Politicians aren’t the only ones at risk in that atmosphere.

Security specialists recommend election workers keep personal social media accounts private so that pernicious individuals armed with AI have less access to their images and voices. To avoid online intimidation on Election Day, experts also suggest election workers use multistep log-ins, ever-changing pass phrases, and fingerprint scanning.

“In 2020, we encountered a lot of ugliness related to threats, and have had to scramble to make sure our people feel safe,” said Schmidt, Pennsylvania’s top election official.

AI-generated misinformation helps exacerbate already entrenched political polarization throughout America, said Cristina Bicchieri, Penn professor of philosophy and psychology.

“When we see something in social media that aligns with our point of view, even if it’s fake, we tend to want to believe it,” she said.

To battle fabrications, Stamm of Drexel said, the smart consumer could delay reposting emotionally charged material from social media until checking its veracity.

But that’s a lot to ask.

Human overreaction to a false report, he acknowledged, “is harder to resolve than any anti-AI stuff I develop in my lab.

“And that’s another reason why we’re in uncharted waters.”

_____

(c)2024 The Philadelphia Inquirer. Visit The Philadelphia Inquirer at www.inquirer.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.