Borrowing an old bromide, when the stock market sneezes, California’s state government catches pneumonia.

It’s more than a common cold when the state coughs up billions of buckets in red ink.

Wall Street recently has exhibited robust health, but Sacramento is still suffering from the market’s fall two years ago.

This is what happens when the state becomes too dependent on rich people for tax revenue. The rich play the stock market and when it pays off, Sacramento reaps a hefty chunk. When the market busts, so does the state budget because capital gains earnings drop.

The market tumbled in 2022. So California’s stock players had less income to report in 2023 — and significantly less in taxes to pay.

“Judgment day is coming, baby,” former state Sen. Bob Hertzberg (D-Van Nuys) said when I called him with new tax numbers. Hertzberg, also a former Assembly speaker, is one of the few politicians who ever had the guts to try to fix California’s flawed tax system.

“I hated the subject with every bone in my body,” he recalls, “but I did it to prevent what’s happening today.”

This is what we’re talking about:

Based on the 2021 tax year, the top 1% of California earners paid virtually half — 49.9% — of the state personal income tax. But when stocks fell in 2022, the top 1% kicked in just 38.7% of the income tax that was collected in 2023, according to new figures just released by the state Franchise Tax Board.

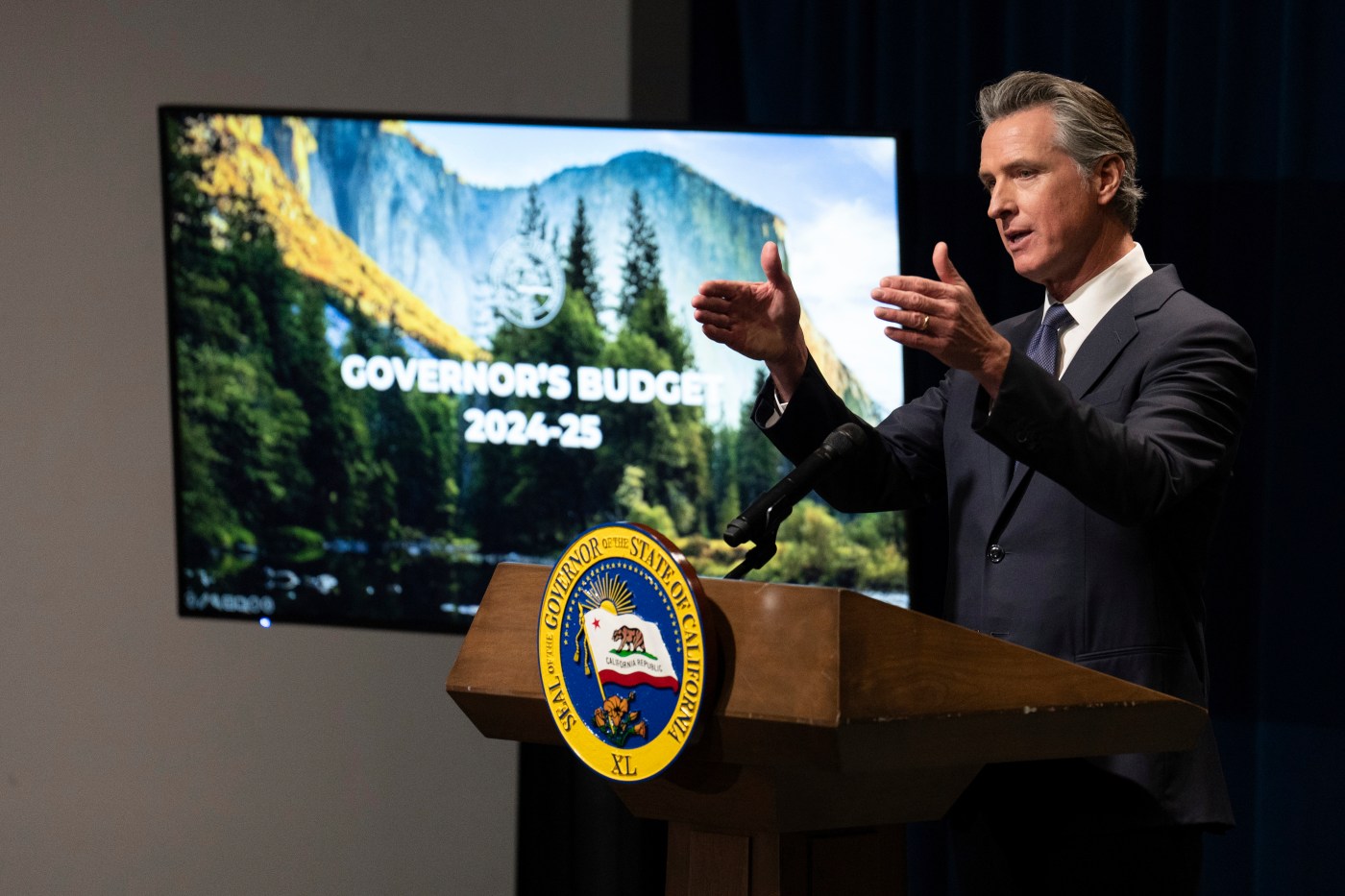

That’s a dramatic drop and it’s primarily why state politicians currently face a budget deficit of around $40 billion, if you accept Gov. Gavin Newsom’s latest numbers from January. But the gap could be as big as $73 billion, according to the nonpartisan Legislative Analyst’s Office.

Cuts are inevitable

Either way, it’s a gargantuan hole in the proposed $292 billion state spending plan Newsom sent the Legislature in January. As he does every year, the governor will revise the budget proposal in mid-May.

Bottom line: Sure, there’s overspending. But California’s fiscal headache is largely the result of an unstable state tax system that relies too heavily on the rich. And politicians are too cowardly to fix it.

After all, “taxing the rich” has a popular ring. It’s an easy sell to most voters who aren’t rich.

But it’s an irresponsible policy that creates chaos in budget planning and drives some well-heeled taxpayers out of the state.

OK, the unreliable tax system makes it tougher on Sacramento budget crafters. So what?

So, there’s a much bigger problem. Programs must be cut that politicians approved two years ago when there was an unprecedented $100 billion budget surplus. Many are worthwhile public services.

Los Angeles Times reporter Mackenzie Mays last week listed several pilot programs now on the chopping block. They include new ways to support struggling foster kids, help oil workers transition to cleaner industries, prevent more people from becoming homeless and fund low-income housing.

If Newsom and the Legislature do their jobs properly, there’ll be lots more cutting before they pass a new state budget by the June 15 deadline. Schools, parks and health care could be targets.

Based on their past records, however, they’ll “balance” the budget with a lot of temporary Band-Aid gimmickry rather than actual spending cuts. Gimmickry such as moving the state payroll date forward by one day into the new fiscal year.

Flatten the tax system

It’s one thing to spend liberally. California’s state government is run by liberals and their political campaigns are bankrolled by liberal interests, after all. But it’s irresponsible not to adequately fund the liberal spending with a reliable tax system.

Here’s another example of how the state relies too heavily on rich people’s earnings: For the 2021 tax year, the top one-tenth of 1% — only 17,900 taxpayers — supplied 29.1% of the income tax. That drastically fell the next year to 19.4%.

The income tax supplies two-thirds of the state’s general fund. Back in 1950, when our tax system was stable, it accounted for only 10%. Then, the sales tax was the main revenue source. But we’ve become less of a retail economy and more of a service economy. And we’re one of the few states that doesn’t tax services.

Our tax system was made even more volatile 12 years ago when, at Gov. Jerry Brown’s urging, voters raised the top income tax rate by 3 percentage points to 13.3%. Now a recession isn’t even needed to blow a hole in the state budget, as we just saw.

The solution should be to flatten the tax system and ease the volatility. Reduce the highest income tax rates and extend the sales tax to services. Not haircuts, lawn mowing and babysitting. But attorney, accountant and architectural fees — things the wealthy pay for — and Dodgers and Lakers tickets.

“That’s exactly the right solution,” Hertzberg says, “but I don’t think it’s possible.”

Hertzberg tried to promote taxing only services that businesses pay — and can deduct on their income tax. “If you can write it off, it’d be taxable,” he says.

“But the politics is just tough.”

People get skittish at the mention of taxing anything that’s not already taxed.

Related Articles

Walters: California progressives play defense as state faces huge budget deficits

Walters: California’s utility charge saga began with misuse of budget process

Opinion: The fallacy behind California’s rollback of water conservation rules

Walters: Newsom’s State of the State should be candid about California’s economy

Walters: Newsom, legislators try gimmicks, wishful thinking to close California’s budget deficit

Former state Controller Betty Yee, who’s running to replace Newsom in 2027, advocated tax reform for years but ultimately backed off.

“I just don’t think there’s an appetite for it,” she says. “With any kind of change, you have winners and losers.”

She got beat up by perceived losers.

California will continue muddling along with a flawed tax system that hurts people when stocks inevitably fall — whether they play the market or not.

George Skelton is a Los Angeles Times columnist. ©2024 Los Angeles Times. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency.