By Kurt Streeter | New York Times

BERKELEY — The controversy began with a walkout.

On Oct. 18, hundreds of Berkeley High School students, with the blessing of some of their teachers, left their classrooms in the middle of the day and gathered at a nearby park.

“Free Palestine!” they chanted. “Stop bombing Gaza!”

“From the river to the sea!”

One of their teachers, Becky Villagran, thanked the crowd of roughly 150, telling them not to forget that the toll of the victims of the war in the Gaza Strip was more than a number.

Just as on the nearby campus of the University of California famed since the 1960s for its marches, sit-ins and progressive ideals students at Berkeley High have a long history of hitting the streets in dissent. In the 1960s, they walked out to oppose the Vietnam War. In the 1990s, they pushed to create ethnic studies courses. More recently, they have shown up in droves to advocate for Black Lives Matter, immigration reform, reproductive rights and LGBTQ+ rights.

But this walkout reverberated in unexpected ways through the Berkeley public school system and the city’s ordinarily tight-knit community.

Some Jewish students, and their self-described Zionist parents, felt frightened by what they saw and heard, including a vulgar shout about Zionism a claim vigorously denied by demonstrators.

Reflecting the complexity surrounding this dispute where symbols, slogans and flags have different meanings to supporters of both sides some Israel-backing parents saw the march and others that followed at Berkeley public schools as hateful.

“Students were chanting, ‘From the river to the sea, Palestine will be free,’” said Stacey Zolt Hara, a Berkeley High parent who has helped organize families to fight against what they believe is a virulent strain of Jewish hatred in the Berkeley Unified School District.

“That chant is a call to wipe out Israel!”

This week, the division bursts onto the national stage. Berkeley schools Superintendent Enikia Ford Morthel is set to appear before a congressional committee in the most recent round of Republican-led inquiries into campus antisemitism. Similar hearings led last year to the high-profile resignations of the Harvard University and University of Pennsylvania presidents and, more recently, to withering criticism aimed at Columbia University’s president.

Berkeley’s public school system, home to roughly 9,000 students, is remarkably diverse. Arabic is the third most spoken language. The city’s sizable Jewish population is reflected in its schools, and students who have strong ties to Israel are not uncommon.

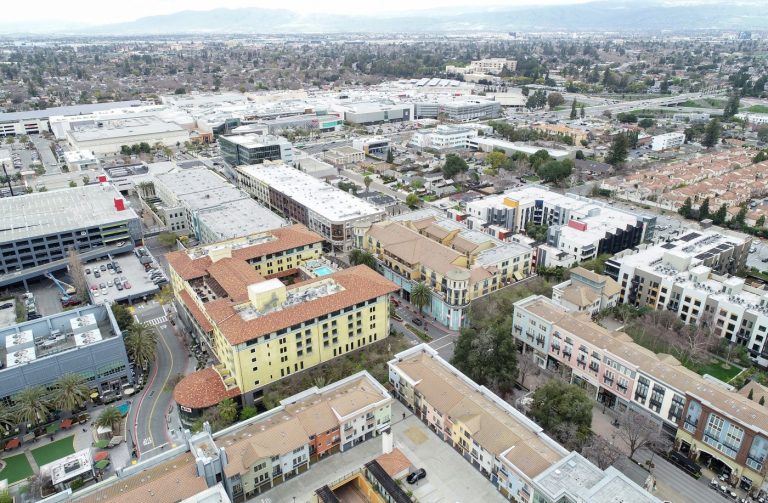

Despite the demographic variation, this is Berkeley, largely uniform in a particular way: It remains the rock-solid bastion of liberal thought that helped birth the 1960s protest movement. In this city of roughly 118,000 smack in the middle of the tech-fueled Bay Area metropolis but still imbued with a good bit of funky, college town feel families, teachers and even school administrators usually operate in lock step on matters of political and social significance.

The shock of the Oct. 7 attack by Hamas on Israel and the resulting bombardment of Gaza has changed the equation.

“There’s a definite fracture,” said one parent, who asked not to be identified for fear of reprisal a common sentiment these days while speaking outside a tense school board meeting on a recent night. “People who were just marching together for Black lives are now at each other’s throats.”

Ford Morthel was summoned to appear after the Anti-Defamation League and the Louis D. Brandeis Center for Human Rights Under Law filed a federal complaint buttressed by information put together by Berkeley residents who back Israel. The 41-page complaint has accused Berkeley’s public schools of allowing “severe and persistent” discrimination against Jewish students, including teachers’ being permitted to indoctrinate “students with antisemitic tropes and false information.”

The leaders of public schools in New York City and Montgomery County, Maryland, are also expected to appear before the committee, the first time K-12 districts have taken the stage in House hearings zeroing in on the response by schools to student protests after the Oct. 7 attacks.

Ford Morthel has been tight-lipped about the request to testify. She released a statement delivered by the district’s chief spokesperson: “Berkeley Unified celebrates our diversity and stands against all forms of hate and othering, including antisemitism and Islamophobia.”

Much of the complaint focuses on the actions of several teachers within the district. One, an art teacher who allegedly showed controversial imagery to his class, including a fist with a Palestinian flag pounding through a Star of David, has been put on administrative leave.

Another teacher is Becky Villagran, 41, who has worked at Berkeley High for a dozen years and currently leads the history department in the school’s international baccalaureate program.

The complaint claims Villagran “expresses antisemitic stereotypes and defamations in class.” As an example of biased teaching, the complaint says that shortly after Oct. 7, Villagran required students to respond to the following question: “To what extent should Israel be considered an apartheid state?”

Villagran denies the assertions, calling them half-truths and lies.

She believes Israel was founded as a settler colonial state. She wears a Free Palestine pin to work. She is also adamant that she teaches the highly charged issues surrounding conflict involving Israel and its neighbors with fairness and through varied perspectives.

The notion that she is antisemitic?

“I’m Jewish, my mom is Jewish, I grew up Jewish,” Villagran says. “I’m not antisemitic. That makes no sense.”

Yes, she admits, she taught a lesson guided by the question about Israel and apartheid. “But we had just been studying apartheid for three months,” she counters. “The timing was just right.”

Villagran also allows that she showed a film that critiqued Israel, as noted in the complaint. For balance, however, she says she gave the students articles showcasing counterarguments. The result, she says, was a classroom buzzing with debate.

“Some kids said it’s not helpful to call Israel an apartheid state, that it’s more about human rights violations,” she said. “Some kids said there are apartheid-like aspects, but the reason is because of security. The lesson was meant to provide both arguments and let the kids decide.”

Villagran’s case is but one example of how Berkeley’s school system is now saddled by claims and counterclaims stemming from the Israel-Hamas war.

After the initial protest, more walkouts took place, and public school board meetings turned heated and sometimes ugly.

These days, people on both sides tell stories of being called vile names or fearing for their safety.

There are activist students who stand up for a cease-fire and push the district to teach them more about Palestine.

There are Jewish students who have taken to hiding their Star of David pendants or their Jewish summer camp T-shirts, and who back the idea that antisemitism in their schools is a severe problem.

There are students, even some from proudly Zionist families, who chalk up taunts about their religion as only a mild bother, the stuff of youthful, misguided teasing sometimes coming from close friends.

There’s a group calling itself Berkeley Unified School District Jewish Parents for Collective Liberation, backing the Palestinian cause and arguing that Jewish students are thriving in their K-12 system.

Opposing them: Berkeley Jews in School, a faction of parents and families formed to press their belief that antisemitism is pervasive on school grounds and at protests.

Ilana Pearlman is one of the parents involved with Berkeley Jews in School. Her son, a freshman at Berkeley High, is mixed part white, part Black and Jewish and she moved to Berkeley because of its reputation for open-minded liberalism. If any city would embrace all aspects of her child’s identity, she believed, Berkeley would be the one.

But her son was in the art class when the teacher showed students the image of the Star of David being punched through with a fist. He heard another teacher speak at a school board meeting, calling Israel a settler colony.

Later, she was crestfallen to find that her son seemed to be keeping his Jewish identity under wraps at school. When she saw the ancestry project he was working on for an ethnic studies class, she was surprised to find he had only included his Black heritage.

“What about your Jewish side?” she recalls asking.

“Mom, it’s not the right climate for that,” he told her.

This story appeared originally in the New York Times.