I received and paid my monthly electric bill from the Sacramento Municipal Utility District the other day.

In addition to $75.76 in metered power consumption and $1.58 in taxes, SMUD’s bill included a $24.80 “system infrastructure fixed charge” that, frankly, I’d never noticed before in decades of receiving SMUD service.

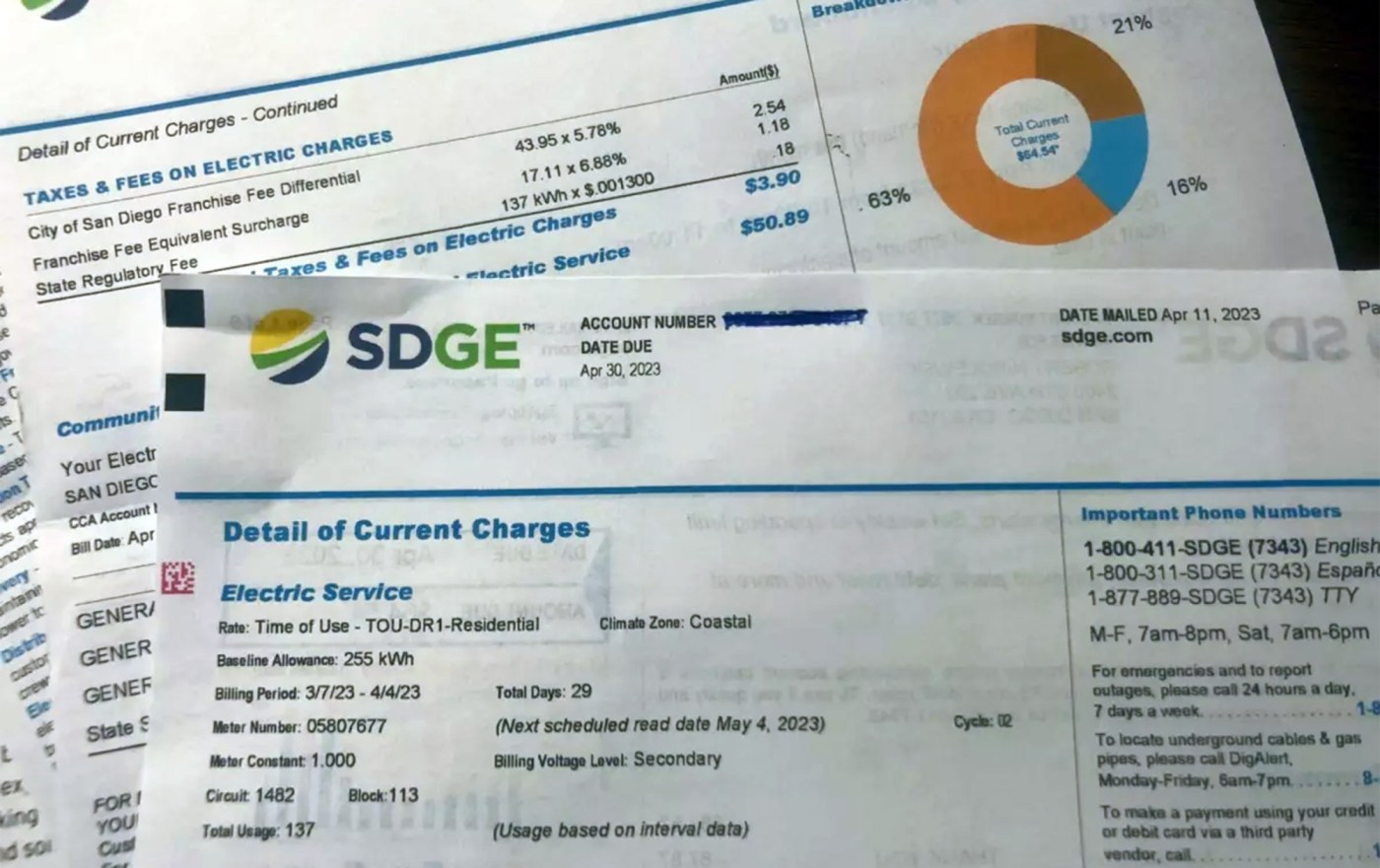

Such charges, meant to pay for the upkeep of the system no matter how much juice is used, are commonly billed to customers of both publicly owned systems, such as SMUD, and investor-owned corporations, such as Pacific Gas and Electric Co., that are regulated by the California Public Utilities Commission.

Fixed charges collected by the latter have long been limited to $10 a month, but that’s about to change, thanks to legislation that was enacted in semi-secrecy two years ago. A few words in a lengthy state budget “trailer bill,” Assembly Bill 205, repealed the $10 cap and ordered the CPUC to create a new charge that would vary by customers’ incomes.

PG&E and other utilities submitted proposals to the CPUC for fixed charges ranging from $20 a month to as much as $128 in three income tiers, as the law required. When they became public, a political firestorm ensued. Critics focused both on the income redistribution principle of the proposed charges and the rather sneaky way in which Gov. Gavin Newsom and the Legislature enacted them.

Eventually, the CPUC compressed the widely spaced tiers in the utilities’ proposals and approved a $24.15 fixed charge — roughly what SMUD and other municipal utilities have been billing — with $12 and $6 for those in lower-income brackets.

The CPUC’s plan also lowers rates for consumption, which will at least partially offset the fixed charges.

There’s nothing wrong, per se, with fixed charges for utility service. Customers should be charged for the maintenance of the distribution systems. However, there’s everything wrong with the way in which the new pricing scheme was enacted.

Newsom included it in one of the dozens of trailer bills his administration drafted for passage late in 2022-23 budget negotiations. It was enacted with virtually no discussion — a classic example of how trailer bills have become vehicles for governors and legislators to make major policy changes on the sly.

It should have been proposed in a separate bill disconnected from the budget, gone through committee hearings and other traditional legislative processes, including debates and floor votes in the state Senate and Assembly.

As a trailer bill, however, it was hastily enacted without such exposure. Thus, many of the legislators who would later criticize the change actually voted for AB 205 without knowing — or caring — what effect it would have.

Last week, Newsom unveiled a much-revised 2024-25 state budget with hundreds of specific expenditure reductions to close a multibillion-dollar deficit. The administration has issued a list of 64 trailer bills it wants to be enacted.

Many — probably most — will in fact be related to the budget. But it’s dead certain that when their details are finally drafted, some will contain significant policy changes that have little or nothing to do with the budget.

Related Articles

Letters: Missing data | Runaway bureaucracy | CalWORKs cuts | State accountability | U.N. peacekeeping

Walters: Newsom’s proposed spending cuts spur backlash from affected California groups

Opinion: Climate change won’t wait for better budget years. Californians need climate bonds now

Walters: Newsom aligns with gloomier budget outlook, blames ‘massive volatility’

Newsom says state has $27 billion budget shortfall, but it can be balanced without raising taxes

Having been burned by AB 205, legislators should pay more attention to what they are being asked to do, and not just rubberstamp the forthcoming torrent of trailer bills.

The late H.L. Richardson was a Republican state senator in the 1970s and 1980s who pioneered the use of technology in political campaigns, with notable success. He also wrote a book, published in 1978, entitled “What Makes You Think We Read The Bills?”

The question is as relevant today as it was 46 years ago.

Dan Walters is a CalMatters columnist.