This year marks the 50th anniversary of the seminal Lau vs. Nichols Supreme Court case. The Court found that San Francisco Unified School District’s Chinese students were not getting the English language instruction they needed to be successful and ordered schools to provide students classified as English Learners equal access to education.

But half a century later, multilingual students are still underserved by schools, both in California and nationally.

Bilingual education can begin to solve this civil rights issue.

California needs to provide adequate funding for bilingual programs, educators and teacher-education programs to ensure greater equity for its multilingual students.

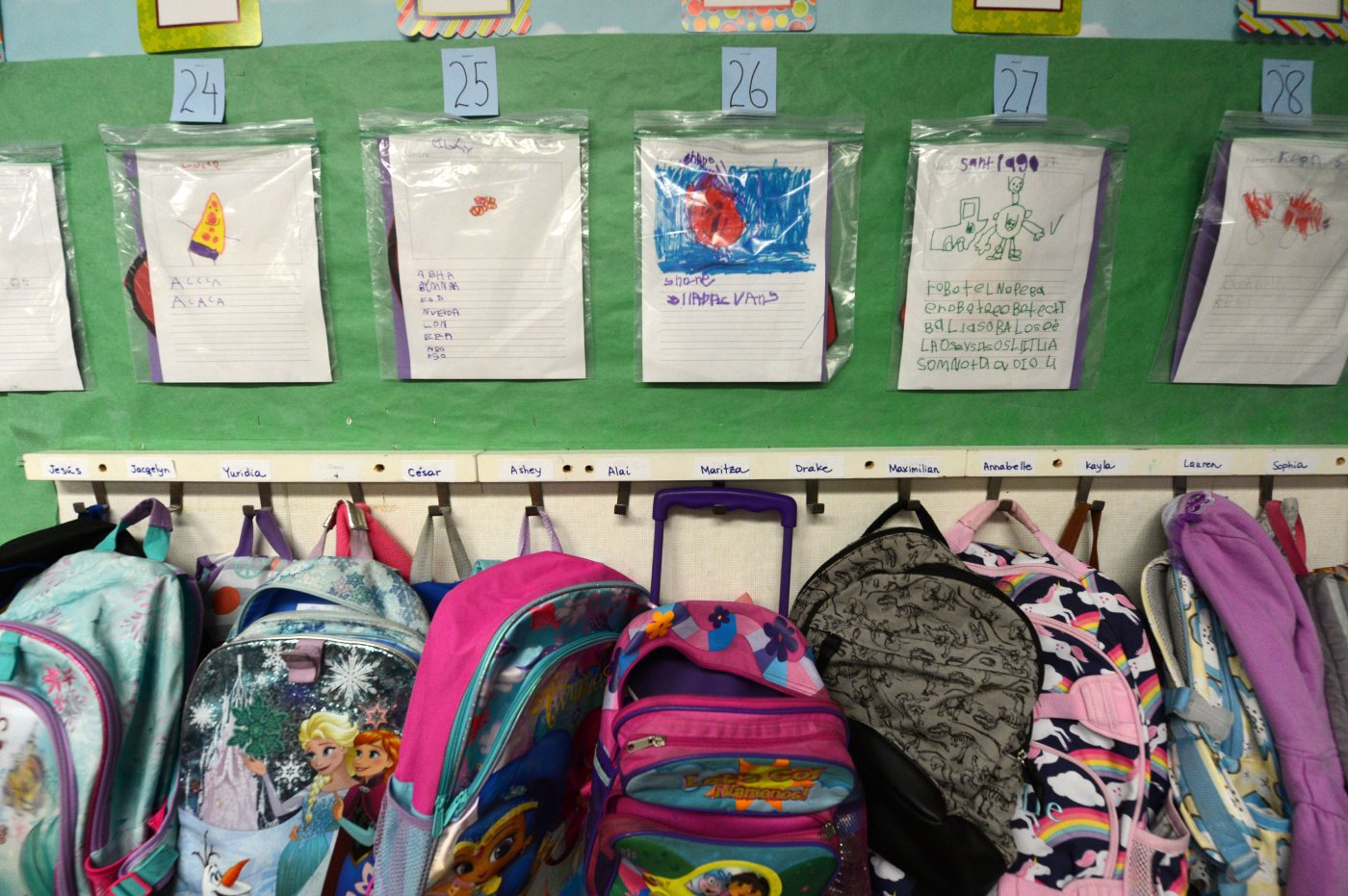

There is an irrefutable research base showing the efficacy of high-quality bilingual education as an educational solution for multilingual students, who comprise 40% of public school students in California.

Multilingual students in bilingual education perform better academically than their multilingual peers who do not have access to instruction in two languages. They have higher scores on English tests of both reading and math when they’re in bilingual education programs. They also achieve higher levels of English proficiency, are more likely to consider higher education, are less likely to drop out of school, and have better social emotional outcomes, such as higher confidence, a greater sense of belonging in school and positive identity development.

Bilingual education also contributes to a school environment where diverse families are included rather than excluded, as bilingual teachers are more likely to communicate with linguistically diverse families and help their English-speaking colleagues to do the same. In fact, bilingual education benefits everyone: English-speaking students also have improved academic outcomes in bilingual programs.

In contrast, multilingual students in English-only programs often do not get appropriate language supports and lack access to college preparation courses. With all these benefits, why aren’t all multilingual students — and all students — provided access to bilingual education?

A recent report showed that fewer than 8% of U.S. students classified as English Learners were enrolled in dual-language programs (a very common form of bilingual education) in 2019-20. California — the state with the largest number of students classified as English Learners — is at the average (8.4%), while the District of Columbia and Texas lead, with 30% and 20%, respectively.

Texas’s success is no accident. The state incentivizes bilingual programs by providing extra funding for each student enrolled in a dual-language program, enabling the schools to purchase high-quality curriculum in both Spanish and English.

While California provides grants for bilingual teacher preparation, funding is insufficient. As a result, the small number of educators qualified to teach in bilingual settings limits the availability of bilingual programs because schools can’t staff them.

Related Articles

New law requires all Louisiana public school classrooms to display the Ten Commandments

Gov. Newsom wants to limit students’ use of smartphones in school

Silicon Valley Pain Index highlights increasing inequity in tech and housing

Vandals rip up Oakland school garden built by Steph and Ayesha Curry’s foundation

Letters: Boon for VTA | SJUSD accountability | Nothing to show | Climate change

Investment is needed to expand bilingual programs to support multilingual students’ success. This can be done through residency programs, local programs for communities to “grow their own” bilingual teachers, making undergraduate teacher education degrees easier to implement, and providing additional funding for instructional aides and early education professionals to get their undergraduate degree and bilingual credential.

At a national level, the Bilingual Education Act of 1968 was imperfect, but it showed federal support for the education of multilingual students and at times, provided funding. New national legislation that promotes bilingual education and provides guidance could help states and advocates advance policy.

We know more about effective bilingual education now; a team of policymakers and researchers could create legislation to support the civil rights of our multilingual students and families. We can solve this if we can garner the political will.

Allison Briceño is an associate professor at San José State University and a Public Voices Fellow with The OpEd Project.