During the summer of 1996, Scott Albert Johnson was covering the Democratic National Convention in Chicago in a highly unconventional manner for the era on his website, Publius ’96: A Virtual Walk Down the Campaign Trail.

The internet was just emerging as a political and media tool. The 26-year-old, who’d recently finished his journalism graduate degree at Columbia University, had no media credentials or steady funding. At night he often crashed on couches in the homes of friends.

Yet the site earned the acclaim of The New York Times, Wall Street Journal and other major media outlets, mainly for its novel approach to political coverage, a phenomenon then dubbed “micro-journalism.” Most of Johnson’s interviews were with ordinary folks in bars, cafes and along the streets of Chicago outside the United Center, in stark contrast to the candidate-centered stories that filled traditional print newspapers and broadcast reports.

“You could argue it was one of the very first political blogs,” recalled Johnson, who now lives in Mississippi and works as a college admissions counselor and professional musician. “I was kind of a gadfly. I was kind of on the periphery of it all. It was a man-slash-woman on the street kind of thing.”

The 1996 Democratic National Convention in Chicago made history as the first DNC where the internet highly shaped political discourse and dissemination of news, allowing everyday Americans to experience a political convention like never before.

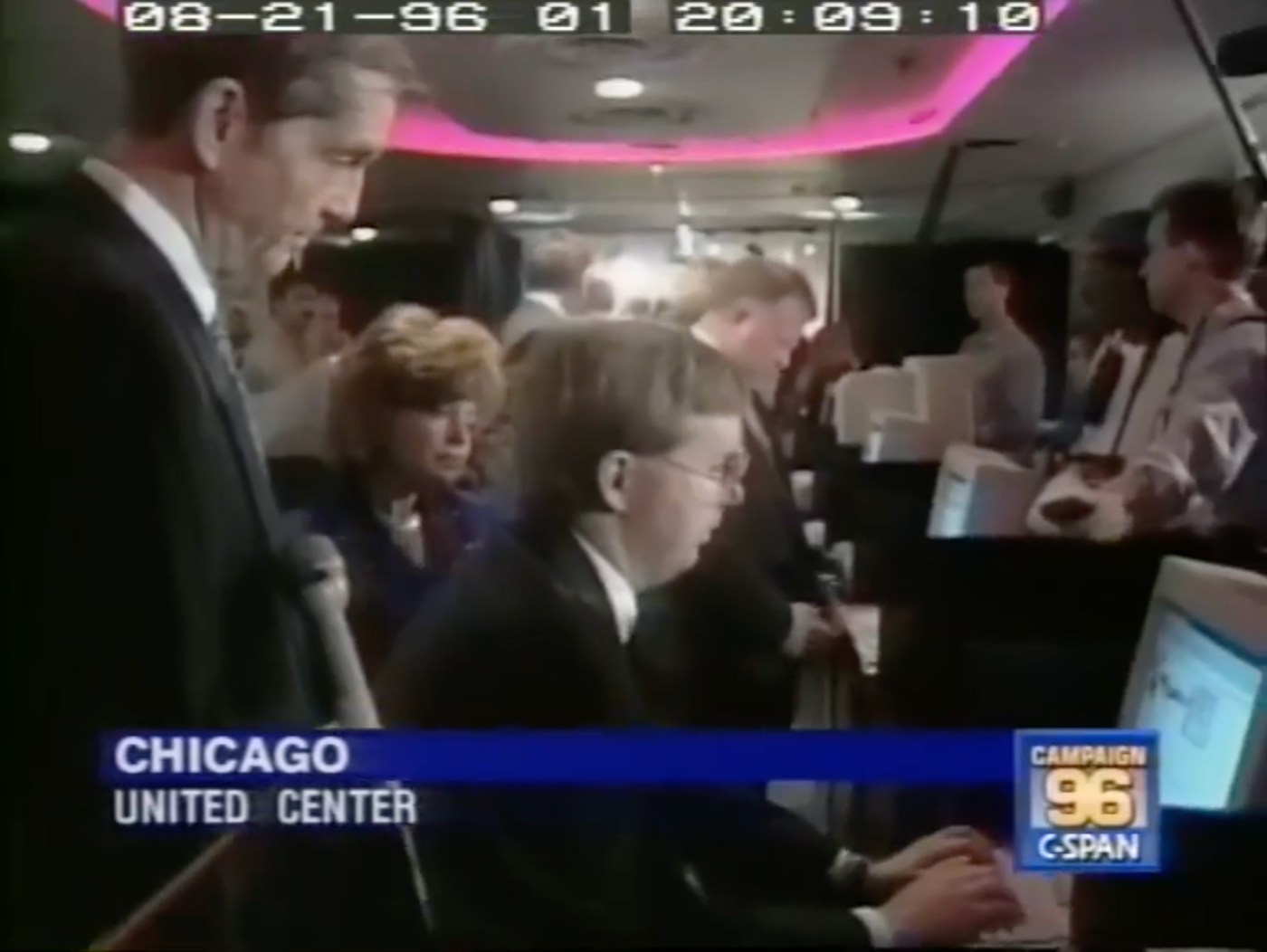

Democratic National Convention Chairman Don Fowler and CEO Debra DeLee give reporters an internet demonstration during the 1996 Democratic National Convention in Chicago. (C-SPAN)

News reporters and camera crews hovered as the DNC’s general chairman and its CEO offered a demonstration of the convention’s internet communication services from a beige-encased cathode-ray tube computer monitor, according to a C-SPAN video of the moment.

“We’re excitedly awaiting the arrival of our state chairs to the most technologically advanced Democratic National Convention. And they’re going to be a part of making it all happen here in Chicago, a wonderful Democratic city that works,” said DNC CEO Debra DeLee, during the demonstration. “The thing that we’re most excited about this whole facility and the Democratic news service is we see it as the best way to communicate with the grassroots.”

Nearly three decades later, the Democratic National Convention in Chicago will mark another evolution in online news and information dissemination: For the first time, the DNC has opened up its credentialing process to online content creators and social media influencers covering the convention — giving them the same access as traditional media outlets — in an effort to reach voters beyond the audiences of legacy media.

Now experts are debating how this change might influence media coverage as well as the outcome of the November election between Democratic presidential nominee Kamala Harris and former President Donald Trump.

The DNC will essentially serve as a “living laboratory,” said Stuart Brotman, professor of journalism and media at the University of Tennessee at Knoxville.

“It may be that social media influencers can in fact maintain the sort of journalistic standards that traditional reporters might, and certainly that would be very positive. Because it means you would have more voices and more people on the ground who can inform potential voters and registered voters,” he said. “On the other hand, if it just results in more noise and innuendo and gossip or other things, it might not eventually contribute to what we fundamentally would all like to have, which is a better informed electorate.”

DNC officials say more than 200 content creators have been credentialed to cover the convention in-person and “hundreds more” are expected to do so virtually.

“Our convention will make history, so we’re giving creators a front row seat to history,” said Matt Hill, senior director of communications for the Democratic National Convention Committee. “While MAGA Republicans revolve solely around Donald Trump, Democrats are reaching Americans where they are with the tools to tell their own stories.”

More than 70 online influencers were credentialed at the Republican National Convention in Milwaukee last month, according to RNC officials.

“The mainstream media’s negative portrayal of President Trump and their willingness to be liberal advocates for Kamala Harris is just one of the reasons American voters have turned to alternative media choices,” said RNC spokesperson Anna Kelly. “Team Trump has been meeting voters where they are for months — from their phones to their front doors.”

Brotman said it will be interesting to see if the coverage of influencers and content creators will translate into more people registering to vote, as well as concrete votes in November.

“We’re going to learn a lot from this,” he said.

Internet boom

While the internet of the mid-1990s was primitive by today’s standards, its novelty laced many aspects of the 1996 Democratic Convention.

The technology was still considered a bit avant-garde: President George H.W. Bush had become the first president to use email in 1992; the White House had just debuted its inaugural website in 1994, according to the White House Historical Association.

In his speech accepting the Democratic nomination in 1996, President Bill Clinton nodded to the power of the internet, declaring that America needed “every single library and classroom in America connected to the information superhighway by the year 2000.”

“Now, folks, if we do these things, every 8-year-old will be able to read, every 12-year-old will be able to log in on the internet, every 18-year-old will be able to go to college, and all Americans will have the knowledge they need to cross that bridge to the 21st century,” he said.

The Chicago Tribune’s website featured “OmniView bubble photograph technology” of the United Center, where “panoramic images from the convention floor can be viewed 360 degrees up and down and left and right,” the newspaper boasted at the time.

In partnership with the DNC, a burgeoning internet company called ichat inc. offered online chats with party elites such as Sens. Jay Rockefeller, John Kerry and Harry Reid, the Tribune reported at the time. A feature called “Soapbox” on the DNC website linked online users with officials who appeared on-screen in a small video window and responded aloud to questions the audience typed in, according to the Tribune.

“That was literally the moment when online and the internet was starting to blow up,” recalled Johnson. “We could see the whole landscape of information changing and, of course, the media business.”

Johnson had been crisscrossing the nation to cover the 1996 presidential election, from the New Hampshire primary to the Republican National Convention in San Diego, sometimes working on a desktop computer he hauled from city to city.

Publius ’96 wasn’t sustainable long term, Johnson recalled. But it left him energized and hopeful about the future of the internet and its impact on media and politics. He recounted a debate with a friend near the project’s conclusion, where he insisted the internet would become sort of an online public hall, offering citizens more access and information while “changing the world for the better.”

His friend was much more skeptical.

“‘What’s more likely is we’re all going to silo off to our own little information holes and actual dialogue is not going to be that great. I don’t see it ending well,’” Johnson said his friend responded.

Looking back, Johnson believes this was the more accurate prediction and he, along with many other Americans, had been a little naïve about the potential pitfalls of the internet.

What passed for political vitriol in 1996 “seems so blissfully collegial now,” Johnson said.

“Bob Dole versus Bill Clinton. These were two guys who, when you really looked at it, weren’t really that different. Now of course it’s a totally different world,” he said. “And all that internet pessimism. … I think we’re seeing it play out on social media — misinformation and disinformation and all that.”

He called the decision to credential social media influencers at the upcoming DNC “a mixed bag.”

Johnson concedes that social media is the dominant way many voters get their information, particularly younger people. He acknowledged that access to credentials would have helped him cover the convention in 1996. But he added that the internet today has become “the Wild West in terms of who puts up information and how credible it is.”

“If Instagram influencers who are basically hawking products are being treated on the same level as people who are really trying to get the truth across to people, I don’t know that that’s a good thing,” he said. “This goes back to my general pessimism about the technology. I don’t know that it’s generated much light as opposed to heat.”

‘Influence the influencers’

Shermann Dilla Thomas, with his tour bus on West 79th Street in Chicago, Aug. 9, 2024, is a social media influencer who will be credentialed for the Democratic National Convention. (Terrence Antonio James/Chicago Tribune)

Chicago historian Shermann “Dilla” Thomas said he’ll be among the online content creators covering the DNC, to capture an important moment in Chicago and national history.

“I’m very much interested in learning about the money the DNC and various caucus delegates are spending outside the downtown footprint,” he said.

Thomas said he believes it would be a mistake for political parties to ignore content creators when some of them might have access to a larger audience than some traditional media outlets.

But he added that it’s incumbent on “content creators who are being blessed to cover something so important that we still use journalistic integrity.”

“That we don’t make stuff up that we say we heard when we didn’t hear it,” he said. “That we vet things. And that we work in tandem with traditional media.”

Today, there are essentially three versions of political conventions, said Jon Marshall, associate professor at the Medill School of Journalism at Northwestern University and author of the book “Clash: Presidents and the Press in Times of Crisis.”

The first is the in-person, traditional experience; the second is the televised version, a carefully packaged partial showing of the convention, which began in the 1950s, Marshall said.

“And now we have the online version of the convention, which is a lot more freewheeling than the other two versions — here we can instantly have a take and an interpretation on the conventions spread around the world in a matter of seconds to millions of people,” he said. “In many ways, that’s probably the most important version of the convention going on live in Chicago, because you can reach so many people so quickly.”

While it’s important that professional journalists continue to cover conventions, “it does seem obvious that you would want to have social media influencers there because they do reach so many people and are so trusted by a large portion of the audience,” Marshall said.

“If you have the opportunity to influence the influencers by giving them access and giving them the kinds of materials that would be helpful to them, it’s going to be a win for whatever political party does that most successfully,” he added.

Politicians have long-recognized that celebrities can influence undecided voters or those who aren’t particularly mobilized to vote, and many social media influencers can be seen as a type of celebrity, said Jennifer Stromer-Galley, professor in the school of information studies at Syracuse University.

Yet she noted the broader problems with political rhetoric on social media and online forums, including political vitriol and misinformation.

“We know from research that messages that are more negative — that attack, that are uncivil — are more likely to spread on social media than positive messages, hopeful messages and factual messages,” she said.

There’s also the conundrum of apocryphal online content: A May report by the Israeli tech company Cyabra found that fake accounts were prolific in political conversations on the social media site X.

Cyabra scanned more than 140,000 pieces of content posted on X from March to early May and found 13% of the accounts discussing President Joe Biden and Trump were fake; of conversations specifically criticizing Biden and praising Trump, 15% of accounts were fake. Of discussions focused on praising Biden and criticizing Trump across all social media, 7% of accounts were fake, according to the report.

“Influencers, I think they have an important role to play in our politics today because they do have such a wide audience of ordinary people who may or may not care that much about politics,” Stromer-Galley said. “My hope is that the influencers who are engaged in politics this election season will do their part to help promote facts and policies over personality and hate.”

In-person convention still critical

The Democratic National Committee intends to stream the convention across a variety of social media and streaming platforms — including X, YouTube, Instagram, TikTok and Facebook — which committee leaders have called unprecedented.

But in some ways, preparations for the DNC illustrate how critical in-person gatherings versus virtual content can be for politicians and activists.

In 1996, various organizations protested the DNC online on anti-establishment websites, featuring groups such as Earth First!, Network of Anarchist Collectives and Seeds of Peace, according to the Tribune.

“The Web allows 1996 activists to push their ideas without getting their heads bloodied as they did in 1968,” a Tribune article at the time stated, nodding to the last Democratic National Convention held in Chicago, which devolved into police violence against Vietnam War protesters that shocked the nation. Riots by “hippie” demonstrators took over the streets of Chicago outside the convention; images of police beating demonstrators were broadcast globally.

In contrast, in 1996 protesters could make statements with “a few clicks of a personal computer’s mouse rather than a few raps of a cop’s club,” longtime political activist Henry DeZutter told the Tribune at the time.

Yet as the next DNC in Chicago approaches, some protesters say online forums can’t replace the power of in-person demonstrations.

“The reason why this thing is so important this year — and why going to be so historic — is we believe there are going to be tens of thousands of people protesting the DNC in the streets,” said Hatem Abudayyeh, co-chair of the U.S. Palestinian Community Network. “There is nothing more powerful than that. There’s nothing more powerful than the people in power seeing real democracy at work. Not representative democracy. Not people who actually make policy based on the interests of corporations that give them money. But actual people who are from the communities who are out and making these demands and making their voices heard and making sure the Democrats hear their message.”

The march route has been the subject of a heated lawsuit, which argued the city of Chicago violated the First Amendment rights of protesters by initially proposing a path in Grant Park that was not within “sight and sound” of the United Center.

The city amended the route last month to begin in Union Park and continue along Washington Boulevard to Hermitage Avenue, then past a park north of the United Center. Protesters fought for a wider, longer path and other demands, but a federal judge has ruled that the city won’t be forced to change the alternate route.

The most recent Democratic National Convention four years ago went fully virtual by necessity, during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“What 2020 showed is that to some degree you don’t need to have in-person conventions,” said Geoff Layman, professor and chair of the Department of Political Science, University of Notre Dame. “You can get by without an in-person convention and it might even be more effective in terms of the product that is being provided to ordinary Americans.”

But Layman’s research found that the success of a virtual convention — marked by Biden’s win in 2020 — didn’t necessarily replace the value of a national in-person gathering to the party or the campaign. He and collaborators at the University of Akron and Southern Illinois University surveyed hundreds of 2020 Democratic delegates; although most described the virtual experience overall positively, nearly 65% of respondents said they would prefer a largely in-person event for 2024.

“You lose what political activists want, which is that in-person experience where they gather with other activists,” he added. “It’s not only fun for them, it’s also important for the party in terms of party-building and developing a campaign apparatus throughout 50 states and 435 house districts across the country. And having these people come all together and talk with each other and meet with each other and share ideas.”

eleventis@chicagotribune.com