A California bill designed to prevent mandated high school ethnic studies courses from veering into antisemitism has been delayed a year amid opposition from teacher and university faculty unions and an Islamic civil rights group who call it censorship.

The bill — AB 2918 — was authored by Democratic Assemblymembers Rick Chavez Zbur of Hollywood and Dawn Addis of San Luis Obispo in partnership with the Legislative Jewish Caucus in the thick of heightened campus tensions over the war between Israel and Gaza.

Despite support from State Superintendent of Instruction Tony Thurmond, the Jewish Public Affairs Committee of California and the Anti-Defamation League, Zbur and Addis decided to push the bill to next year’s legislative session to allow for more time to work with opponents.

“We came to the conclusion that there were some valid concerns that were going to take longer for us to work through than we had time at the end of the session,” Zbur said.

Zahra Billoo, executive director of the San Francisco Bay Area office of the Council on American-Islamic Relations, said the organization is open to being brought into the conversation but doesn’t support removing curriculum developed by educators.

“We had opposed this bill because it appeared to be an effort by legislators with an apparent pro-Israel bias to problematically influence ethnic studies,” Billoo said. “I worry that it is disingenuous to malign ethnic studies efforts as antisemitic in the way that some legislators and advocates have attempted to do.”

The bill was introduced in response to a state mandate requiring California’s public schools to offer a course in ethnic studies beginning next year. By 2030, students won’t be able to graduate without it.

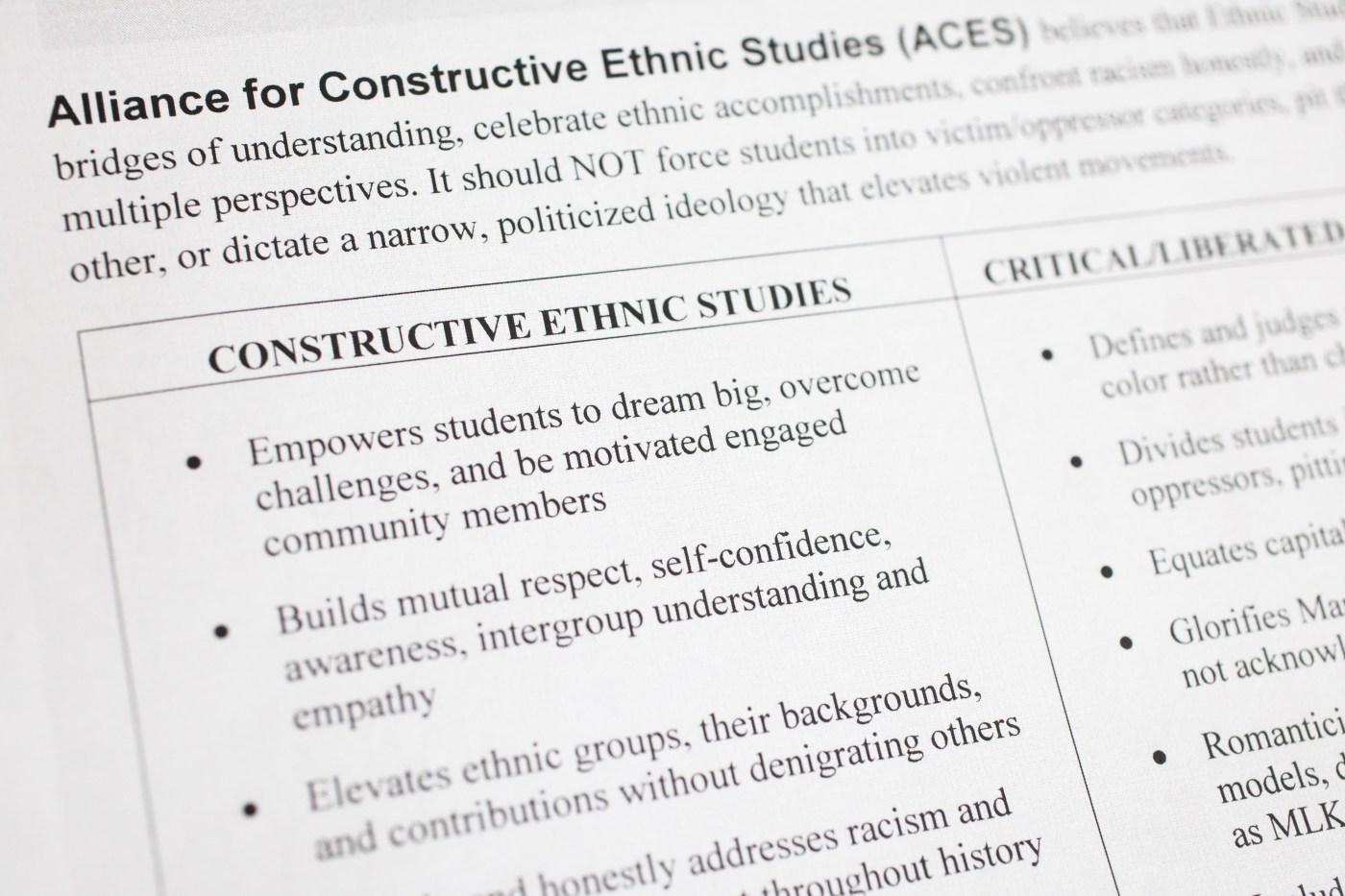

The state passed a model curriculum for the course — which examines the history of race and ethnicity in the United States — in 2021. And while districts are mostly free to design their own courses, competing visions for how to teach ethnic studies has incited statewide conflict among school districts.

“I get multiple calls about this in my district office every week,” Zbur said. “There are cases that are popping up around the state where we’re seeing curriculum that is just clearly inappropriate . . . We want to make sure that ethnic studies is something that uplifts all students.”

Several Bay Area schools have been caught in the crossfire amid claims their course content is antisemitic.

The Deborah Project, a law firm advocating Jewish civil rights, has sued Mountain View-Los Altos Union High School District and Hayward Unified High School District, citing “overtly” antisemitic teaching materials in their coursework.

Sequoia Union High School District, Morgan Hill Unified School District and Berkeley Unified School District are also facing backlash from community members for their ties to a controversial version of the course being offered to school districts.

Tyler Gregory, CEO of the Jewish Community Relations Council Bay Area, said the organization hopes to partner with the Jewish Caucus and other ethnic caucuses on new legislation to ensure ethnic studies is taught in a fair and inclusive way for all students.

“Unfortunately, in too many cases, the Jewish American experience in ethnic studies has been marginalized and antisemitic tropes have been introduced — leading Jewish students and families to feel vulnerable and isolated,” Gregory said.

If passed, AB 2918 would have required districts to work with “a majority” of teachers, parents and community members to review proposed ethnic studies courses before approving them. The bill also would require schools to submit a detailed explanation if they choose to develop a course differing from the state model curriculum.

But the bill was met with opposition from parents, educators and community leaders who said it would add an additional layer of state oversight and shift decision making away from educators.

In a letter to Gov. Gavin Newsom and Superintendent Thurmond last fall, the University of California Ethnic Studies Faculty Council expressed “deep concern about the censorship of ethnic studies” through “guardrails” like AB 2918.

“We vehemently oppose the preemptive restriction of what can be taught, examined and researched as part of ethnic studies,” the letter said. “Such restrictions risk replicating the very forms of oppression and erasure of knowledge that the field seeks to rectify.”

Zbur said the idea behind AB 2918 is not to remove educator input but to simply ensure that schools’ curriculum is meeting state requirements for students.

“Part of the problem is that we don’t have the same level of review and guardrails (for ethnic studies) that are generally put in place for other kinds of curriculum that we bring into the classroom in the state of California,” he said.

Zbur said pushing the bill to next year will give him and other legislators time to have “deep dialogue” with educators from the California Teachers Association and California Faculty Association and successfully get their support for next year.

“We both want a robust ethnic studies curriculum to be part of California’s school curriculum, one that is guided by the experiences and the challenges of the ethnic communities that it is intended to serve,” Zbur said. “But at the same time, make sure that the curriculum is also appropriate for all students in the classroom.”