After being evicted from her apartment, Juanita Campa was homeless for years, eventually coming to live with her 4-year-old son and his father in the Jungle, an encampment along the edge of San Jose’s Coyote Creek.

More recently, though, they moved into a hotel that serves as transitional housing for homeless children and their families. Campa’s next goal? To get her son, Sergio, who has been diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder, enrolled in kindergarten.

“He’s a very smart kid,” Campa said. “He listens.”

Campa also hopes to move her family into a more permanent living situation. But until then, Sergio will be among the rapidly growing ranks of unhoused students in South Bay schools. Since 2020, the number of homeless students in Santa Clara County has almost doubled, according to the California Department of Education.

About 1,200 students in the East Side Union High School District and Alum Rock Union School District were reported to be homeless in 2024 — three times the number of homeless students in 2020.

Three other counties in the Bay Area — Alameda, Contra Costa and San Mateo — had between 2,100 and 4,700 homeless students enrolled in their schools in 2023. According to the state, 10% to 12% of those students were living in temporary shelters that year.

In the Alum Rock district, Superintendent Imee Almazan said the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated multiple economic issues that were out of the parents’ and the school district’s control, leading to the increase in homeless youth.

“It goes back to economic hardships, loss of jobs, displacement. There’s just a number of reasons why our families are growing in our (homeless youth) population,” Almazan said. “And some of our families haven’t bounced back from that yet.”

Maryam Adalat, director of student services at East Side Union High School District, said many families have lost stable housing, their jobs or loved ones who were the family’s main provider since the COVID-19 pandemic.

Adalat said district staff have seen many families facing unstable housing and multiple families living in a household. “We have students who are living in shelters. We actually have foster youth that are unhoused as well,” she said.

Out of the 1,974 homeless students enrolled at East Side in 2022-2023, 488 were living in temporary shelters, according to the state education department, while 75 students were living in hotels and motels, and 33 students were temporarily unsheltered or living in abandoned buildings, campgrounds, vehicles, trailer parks or train and bus stations.

A part of the homeless encampment along Coyote Creek near Story Road is seen in San Jose, Calif., on Tuesday, July 23, 2024. (Dai Sugano/Bay Area News Group)

That same year, a majority of homeless students in the district were unable to pass the Smarter Balanced Summative Assessments, standardized tests for mathematics and language arts. Around 78% of homeless students were unable to meet the standards for mathematics, while 51% were unable to meet the standard for language arts.

Annya Artigas, the director of Social Emotional Learning at the Alum Rock district, said homelessness can affect students inside and outside the classroom. For example, many homeless children struggle to find timely transportation to school, and once they arrive at school, the only meal they may eat is their school lunch.

Some homeless students may also miss class or arrive late because they live in temporary shelters outside of the district. In order to get to school, they use public transportation to travel across town.

“There are a number of kids that we knew who were homeless who would show up late. Before we brought them to the classroom, we bring them to the cafeteria and grab them something to eat and grab them some milk so that they can have something in their stomach before they went into the classroom,” she said.

As a result of these different stressors, homeless children may also struggle to stay mentally present in school, Artigas said. Many come to school sleepy, tired and hungry, impacting their ability to function in the classroom.

“Whenever a child presents inside a classroom, all of those things come with that child. And all of those things are impacting their ability to engage, their ability to receive information and process it and retain it,” Artigas said.

Maureen Smith, a professor who teaches childhood adolescent development at San Jose State University, said children experiencing homelessness without a guardian are also less likely to be enrolled in school. She said some children are forced to leave their homes because of domestic violence or because of their gender or sexual identity.

“They leave the home really traumatized to begin with, and then they end up on the streets,” Smith said.

Without a guardian, these children may not know how to enroll into school. They may also be hesitant to go to a shelter because some programs require identification. As a result, children may avoid going to shelters or schools because they don’t want to sent home to their parents.

Back on the East Side, Campa said Sergio will be able to go to school soon, but she doesn’t know when. She’s waited for more than two months to get a phone call back from the McKinley-Franklin and San Jose Unified school districts. She started filing Sergio’s paperwork over a year ago.

She doesn’t like to think about how her family used to live in the Jungle. Now she has less than 90 days remaining at the hotel.

“I felt like I wasn’t doing my job as a mom because we’re homeless,” she said “We were working but it wasn’t enough. … I don’t want to be back here.”

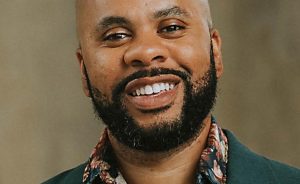

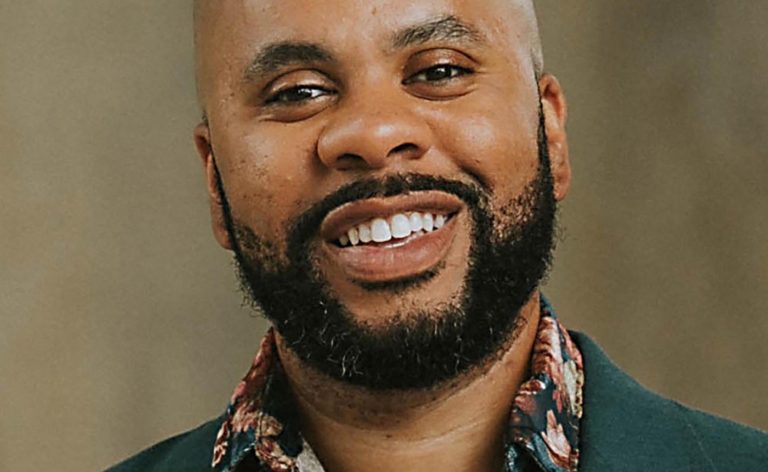

Juanita Campa becomes emotional as she talk about the time she and her family lived at this homeless encampment along Coyote Creek near Story Road on Tuesday, July 23, 2024, in San Jose, Calif. The family is currently living in an interim housing program site in San Jose. (Dai Sugano/Bay Area News Group)