People in urban communities of the Bay Area are likely already used to the screech of tires that can signal the presence of a nearby “sideshow” or street takeover. Although this aspect of car culture is native to Northern California, police are cracking down on them due to the dangers and inconveniences posed.

Q: What is a sideshow?

Sideshows are informal, and often illegal, car shows where drivers perform tricks in front of a crowd, often taking place in vacant parking lots or even in wide street intersections. Some sideshows have happened in high-profile locations like the Bay Bridge.

According to San Jose Deputy Police Chief Brandon Sanchez, the term “sideshow” was a spin-off of “high-siding,” when a person sits on the passenger side window of a car while someone else was driving. The term evolved as high-siding became a spectator sport into sideshows.

Q: What happens at a sideshow?

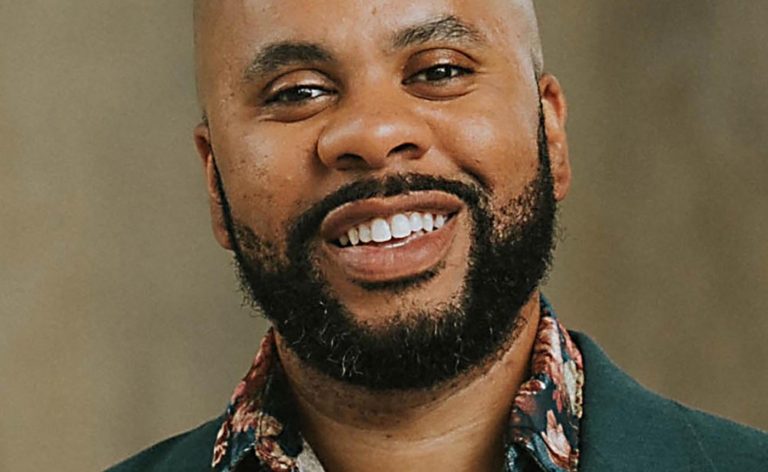

Oakland native and Northeastern University professor Mario Hernandez said that sideshows were based in a masculine, muscle car culture around classics like Ford Mustangs, Chevrolet Camaros and Dodge Chargers. Although some people showed off their cars by washing them before an event, sideshows also attracted drivers with older, junkier cars, he said. There was a DIY aspect to the culture, with people hooking up amps and wires through their car.

“It’s an extension of yourself in a lot of ways, because it’s like you put time and energy and money into it,” Hernandez said.

Sideshows commonly include racing and driving donuts with the doors open. An infamous and dangerous trick is ghost-riding, which is when someone exits a car while it is in drive and stands or dances in the street alongside the moving vehicle. Hernandez said another common sight is people sticking out of the sunroof as someone else drives.

Sideshows in the Bay Area have taken place at all times of the day and night, sometimes running into the early hours of the morning.

Q: Why are sideshows illegal?

Although young people participating and watching sideshows in the past kept their activities to abandoned or unused areas, like parking lots, Tilton said local businesses and city leaders complained about tire tracks in the street and the noise in the late evening and early morning hours caused by drivers, large crowds and loud music, leading to police cracking down.

Aside from the danger posed by the stunts performed by drivers, Sanchez said violence has been increasing around sideshows. He gave examples of stolen vehicles, assaults and people in the crowd carrying guns and shooting them off into the air. He also pointed to looting and vandalism of storefronts near intersections where sideshows occur.

While the crackdowns pushed some events into neighborhoods and smaller street intersections, other sideshows moved to large arteries, like Stevens Creek Boulevard and Winchester Boulevard, which interrupted the flow of traffic. When police came to bust drivers, the resulting car chase became a part of the thrill and added to the danger.

Additionally, because sideshows would attract large crowds, Sanchez said it can take “almost a small army” to break up the activity, which puts a strain on the police’s resources when they are needed elsewhere.

Q: What is Bay Area law enforcement doing about sideshows?

For as long as sideshows have existed, expression and enforcement has been a cat-and-mouse game between promoters and police. People driving in sideshows can be charged with a misdemeanor offense such as reckless driving, and face a number of penalties, including fines, jail time, vehicle impoundment or driver’s license suspension. In some California cities, including San Jose and Oakland, watching a sideshow could be punishable with fines, jail time, probation or community service.

Since the early 2000s, Oakland has passed a series of laws criminalizing sideshows, enabling police to seize involved cars and ticketing people for watching them.

The Oakland Department of Transportation introduced a pilot program in 2021 intended to curb sideshow activity: One part included building curb extensions and traffic islands to reduce the number of intersections where a sideshow could take place, and another focused on modifying street surfaces with different materials, like steel plates, to deter sideshow activities in a low-cost way.

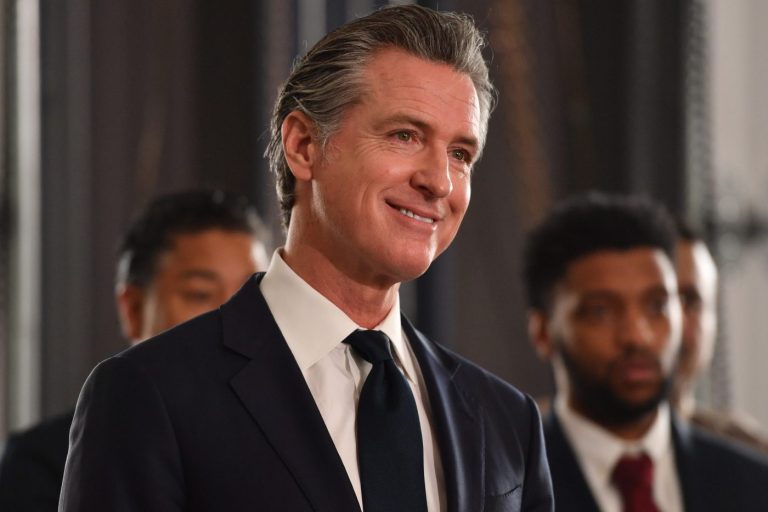

In San Jose, Sanchez said the police use a variety of strategies to find and break up sideshows and their organizers, leading to a “nice downward tick” in sideshow activity in the South Bay city. They monitor social media to find out when and where a sideshow might occur and schedule more officers on duty, if possible. They also also use license plate reader cameras and other intelligence to identify promoters, spectators and the cars they drive. Because sideshows can quickly move from intersection to intersection, Sanchez said they also share information with other Bay Area jurisdictions to identify drivers and vehicles.

“What we’ve tried to do in San Jose is try to bring some awareness to sideshows, the violence that actually comes with it,” Sanchez said.

Q: How did sideshows first start?

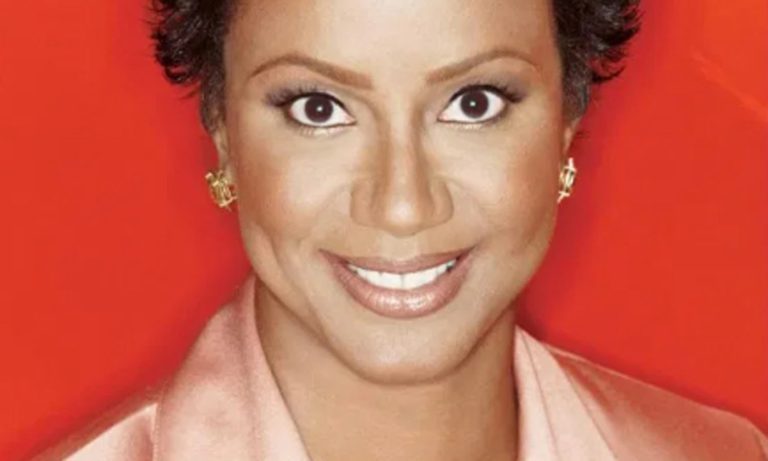

Sideshows first started coming onto the scene around the late 1980s and early 1990s, said Jennifer Tilton, a professor of race and ethnic studies at the University of Redlands.

One of the most notable places where sideshows took place was the Eastmont Mall parking lot, she said. Formerly a car factory in the early 20th century, the location provided jobs for working class people. But as East Oakland integrated in the late 1960s, the predominantly white community in the area moved out to the suburbs, taking their businesses and their capital with them.

The mall — built in the early 1980s to serve a burgeoning population of mostly Black middle class residents — was on the decline by the end of the decade, leaving young people without a major recreational outlet.

Tilton said the young people in East Oakland, specifically young Black people, at the time told her that there was “nothing to do in East Oakland” and there were “no spaces in which they were welcome.” So, sideshows were born out of their boredom and lack of public space where they could come together. And in the early days, it was seen as a positive thing young people could do with their time as an alternative to getting involved in the drug market.