For an hour and a half, 56-year-old Sean Ogden shuffled down the side of the PCH as Malibu burned.

Related Articles

Southern California wildfires add to growing worries about homeowner insurance

San Jose business leaders offer support to L.A.-area businesses as fires rage

VP Kamala Harris’ Brentwood neighborhood evacuated amid L.A. wildfires

Bidens’ trip to Southern California was eventful, but nothing like planned agenda

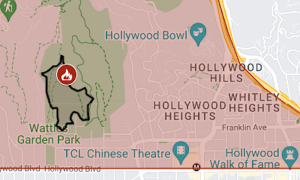

Map: Where the Sunset fire is burning in the Hollywood Hills

It had long been home, in one form or another.

Ogden lived in a tent in Tuna Canyon Park, and he was evacuating by foot Wednesday afternoon, grizzled face caked in soot from a rampaging Palisades fire that had yet to reach any form of containment.

His right shoulder carried a purple Adidas bag, filled with a couple of electronics and a bottle of shampoo.

His left hand lugged the rusty handle of a shovel — in case, as Ogden said, he needed to “put some dirt on a fire.”

“It’s kinda hard,” Ogden said, squinting as ravaging winds off the nearby sea whipped in a cloud of smoke. “It’s kinda weird. Like you’re on a different planet.”

The small town of Malibu became a ghost town by Wednesday, in the midst of widespread evacuations from the Palisades fire that resident Veronique de Turenne called “apocalyptic,” leaving the scenic route down a normally pristine slice of Southern California unrecognizable.

RELATED: Trump blames Newsom for Southern California wildfires, governor’s office pushes back on facts

Stretches of decades-old homes lining the PCH, jutting out over ocean views, were left burnt down to their concrete foundations. Upturned telephone poles littered the roads; parked cars on the shoulders reduced to charred hunks of metal. Crews of firefighters packed the streets, for miles, trying to preserve what is left of an iconic staple in California.

“It’s just absolutely terrible,” said 40-year Malibu resident Norm Haynie, standing on a stretch of road a mile down from the Malibu Pier, watching an apartment billow up in smoke. “I think, probably the worst fire in 15 years.”

Indeed, the Palisades fire will stand as the most destructive in Los Angeles’ history, according to statistics reported by the Associated Press Wednesday.

After evacuating, residents Jason and Enna Burt returned to the house Jason grew up in, where they still lived.

They drove as close as they could, parking at the bottom of the hill at the PCH and Temescal Canyon Road and then walking some two miles up to his house.

“I was just hoping for a miracle,” Enna said.

But their home was gone.

Also gone, amid an estimated 15,832 acres burned and 1,000 structures destroyed — so far — are longtime staples of Malibu’s ecosystem, a community teeming with history despite its dazzling surface-level reputation.

“There are a ton of people who have been there for generations whose families have had homes there, and I’m not talking about mansions,” said Malibu resident Elle Johnson, who lives on Malibu Road, down from the PCH. “I’m talking about just kind of blue-collar, working-class people, farmers and just other people living off the land who really love it there and love the nature.”

Remnants of the oversized blue chairs and yellow table that welcomed patrons to Rosenthal Wine Bar & Patio were all that remained of the popular spot, according to the wine bar’s social media. Rosenthal shared those images — as well as messages and photos from patrons sharing memories from times past — on its Instagram page Wednesday.

Gone is the iconic Reel Inn seafood restaurant, owners Teddy and Andy Leonard writing in an Instagram post they were “heartbroken and unsure what will be left.”

Gone, too, is the Malibu Feed Bin, a pet food and supplies store that’s been a community staple for 60 years.

“We lost the Feedbin today,” a Facebook post on the store’s account relayed. “This is so unreal for me, and I having a hard time finding the words that even make sense.”

Further up and across the PCH, Duke’s Malibu on Wednesday said it was still standing, for now.

“The situation is unstable and still very dangerous,” the restaurant said. “Please keep our ‘ohana and everyone affected by this tragedy in your prayers.

Fire crews came rushing in from beyond Los Angeles to arrive in Malibu, with one crew from Monterey getting a call from assistance at 9 p.m. and driving south throughout the night, firefighter Patrick O’Brien said.

On Wednesday afternoon, O’Brien stood with a group of firefighters in front of one house on the ocean side of the PCH, the front door agape and hallway engulfed in flames. They’d spent four hours since that morning, O’Brien said, trying to hose down the home.

It hadn’t worked.

They’d resolved, O’Brien explained, to simply control the burn enough for the house to collapse in on itself and not spread to a nearby home.

He was surprised at how quickly the fire had spread, remarking there were too many houses for the resources they had. When his crew first was notified, O’Brien said, the Palisades fire was just around 2,000 acres. Seven hours later, they arrived at 4 a.m. into what “felt like a hurricane,” O’Brien said.

“That wind,” O’Brien said, “is just insane.”

That wind, in fact, was the warning sign for a slew of residents, many of whom had lived through multiple Southern California wildfires in recent years.

De Turrene, who lives on a bluff above Malibu’s Carbon Beach, saw news of a 20-acre brush fire erupting in the Palisades highlands Tuesday. Her neighbors, she recalled, shrugged it off: “Oh, that’s so far away.”

“But I’ve lived in Malibu since 1995,” said de Turrene, an author and journalist, “and I knew that that wasn’t far away.”

She’d lost power Tuesday night, de Turrene said, unable to even receive an alert she was in an evacuation zone. She and a family next door stood watch, each taking turns throughout the night to stroll down to the PCH and check the fire’s progress. And then at 1 a.m., as de Turrene put it, “the wind hit us.”

She and Ogden and scores of others left behind a town that’ll be forever changed, one-time beachfront shacks turned to mansions turned to piles of ash. Restaurants like the Reel Inn, as Johnson put it, made Malibu “feel like home,” a community caught between peaceful simplicity and millionaire mystique.

Johnson has evacuated Malibu three times, in just the last three months, due to fire concerns. When she returned to greater Los Angeles, she said, she would notice people were not fully aware of what was happening up the PCH. Malibu wasn’t far. Roughly 20 miles.

“But it feels like a world away,” Johnson said, “which is, you know, what makes Malibu so magical.”