Ultimately, responsibility for the fatal fentanyl and methamphetamine overdose of 3-month-old baby Phoenix, and for Santa Clara County’s broken child welfare system, rests at the top.

That’s the county Board of Supervisors. For too long, the elected leaders have voiced concern but haven’t taken the necessary steps to hold accountable those responsible for the dysfunction that places innocent children in danger.

The five-member board this year has two newcomers. Now is the time to commission an independent review of the seemingly failed leadership of County Executive James Williams, Social Services Agency Director Daniel Little, and Damion Wright, who recently announced his resignation as director of the Department of Family and Children’s Services.

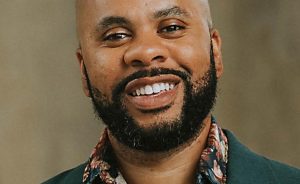

Santa Clara County Executive James Williams (Shae Hammond/Bay Area News Group)

They are the leaders who embraced the 2021 policy that prioritized keeping families together over keeping children safe. It’s that policy that led to the death of baby Phoenix Castro in 2023.

A social worker had warned superiors of the risks to newborn Phoenix if she was sent home from the hospital. Her older siblings already had been taken away from drug-abusing parents.

But Phoenix was sent home anyway. Her mother, Emily De La Cerda, died of a fentanyl overdose months after the infant’s death. Her father, David Castro, is facing felony child endangerment charges.

This news organization’s investigative reporting on the tragedy publicly revealed the fissures in the county’s children protection system that Williams, Little and Wright already knew about.

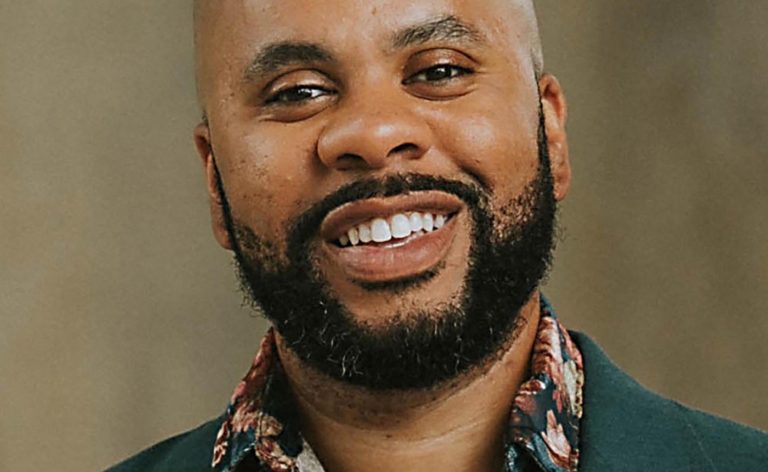

Santa Clara County Social Services Agency Director Daniel Little gives a presentation with Damion Wright, left, director of Department of Family and Children’s Services, defending their family preservation policies. (Dai Sugano/Bay Area News Group)

It turns out that, even before baby Phoenix’s death, state investigators from the California Department of Social Services were probing the county agency’s failed practices.

At the center of the controversy was the county’s policy that prioritized keeping children with their parents. There’s a legitimate debate about how to balance the importance of keeping families together vs. the risks of leaving children in unsafe homes.

But the county’s approach tipped far in the wrong direction, leading to the decline from 60 removals of children from their homes in 2020 to 20 in 2022.

A state report in February 2023, the same month baby Phoenix was born, found that the county counsel’s office frequently overrode decisions by social workers to remove kids from unsafe homes.

A second scathing state report, issued in July 2024, more than a year after Phoenix fatally overdosed, described more shocking breakdowns in procedures.

For example, in 55% of cases where social workers had concerns about the well-being of a child who remained in the home, no plans had been developed to ensure the safety of the youngster.

Children who reported parental abuse were required to have parents present during interviews with social workers. And decisions about whether children should be removed from their homes for their own safety were still being driven by county attorneys without input from front-line social workers.

County officials have finally started to address some of these issues. But, as reporter Julia Prodis Sulek noted last month, those front-line workers remain understaffed, demoralized and lacking confidence in their bosses.

That’s not surprising. Because this is not just a story of failed policies but also of failed leadership, which is beyond the scope of the state investigation.

For now, the leaders of the 2021 policies remain in charge. Sure, Wright, a champion of the failed policies, is departing, effective Friday. But he wasn’t in charge of the department four years ago.

Related Articles

After Santa Clara County child welfare agency director resignation, social workers call for more changes

Santa Clara County child welfare official resigns a year after infant’s fentanyl overdose rocked community

What’s Santa Clara County done since Baby Phoenix’s death a year ago to better protect vulnerable kids?

Fremont mother sentenced in fentanyl overdose death of 23-month-old son

Little was — and then he was later promoted. He’s accountable to Williams, who, in turn, reports to the Board of Supervisors.

Williams’ involvement is also problematic. He became county executive in July 2023, months after baby Phoenix’s death. Before that, he was the county counsel, ultimately in charge of the attorneys faulted by the state for overriding the judgment of social workers.

In other words, for an accurate assessment of the performance of their top leaders in this debacle, county supervisors will need an independent, outside investigator.

That review is long overdue.