By MARCIA DUNN

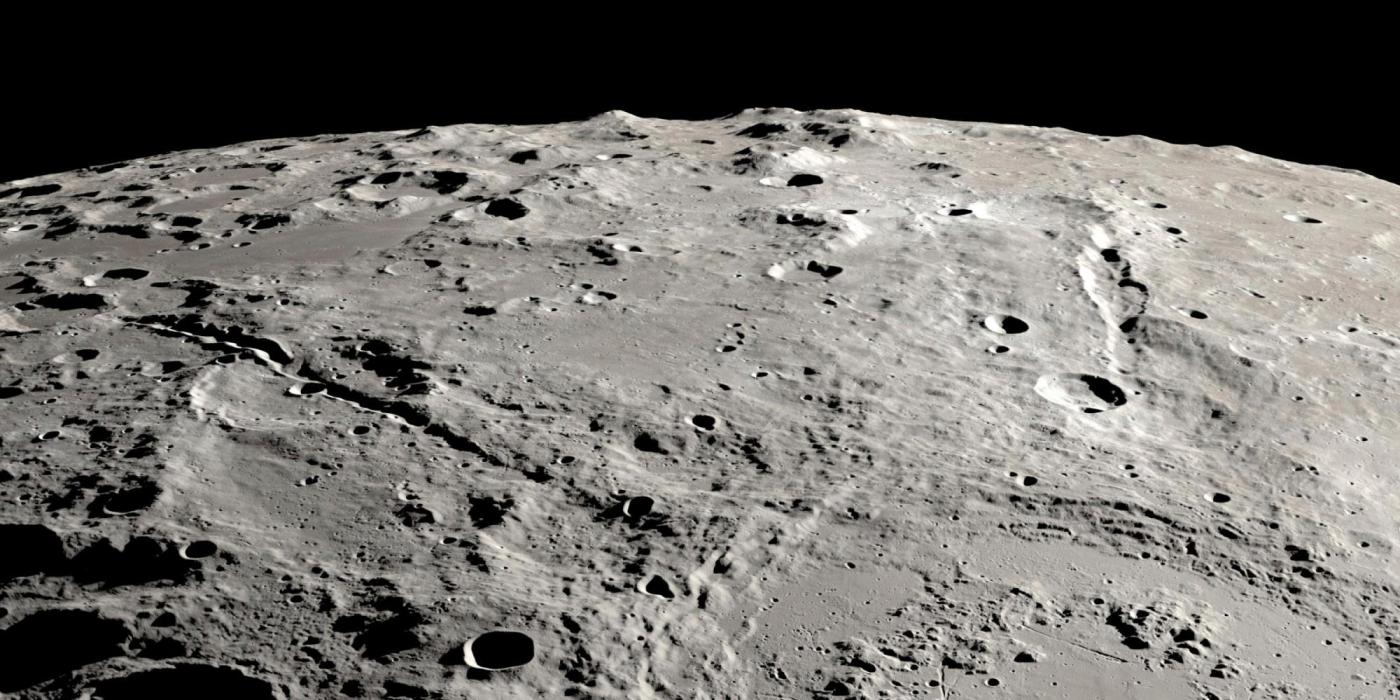

CAPE CANAVERAL, Fla. (AP) — New research shows that when an asteroid slammed into the moon billions of years ago, it carved out a pair of grand canyons on the lunar far side.

Related Articles

Jeff Bezos’ Blue Origin mimics the moon’s gravity for NASA experiments during spaceflight

Bay Area housing complex for elders reports large COVID outbreak

‘We have an amazing piece of the planet here’: Monterey Bay Aquarium’s Julie Packard to retire (sort of) after 40 years

Growing abalone beneath the Monterey Wharf

Ancient alphabetic writing unearthed by UC Santa Cruz professor remains a mystery

That’s good news for scientists and NASA, which is looking to land astronauts at the south pole on the near, Earth-facing side untouched by that impact and containing older rocks in original condition.

U.S. and British scientists used photos and data from NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter to map the area and calculate the path of debris that produced these canyons about 3.8 billion years ago. They reported their findings Tuesday in the journal Nature Communications.

The incoming space rock passed over the lunar south pole before hitting, creating a huge basin and sending streams of boulders hurtling at a speed of nearly 1 mile a second (1 kilometer a second). The debris landed like missiles, digging out two canyons comparable in size to Arizona’s Grand Canyon in barely 10 minutes. The latter, by comparison, took millions of years to form.

“This was a very violent, a very dramatic geologic process,” said lead author David Kring of the Lunar and Planetary Institute in Houston.

Kring and his team estimate the asteroid was 15 miles (25 kilometers) across and that the energy needed to create these two canyons would have been more than 130 times that in the world’s current inventory of nuclear weapons.

Most of the ejected debris was thrown in a direction away from the south pole, Kring said.

That means NASA’s targeted exploration zone around the pole mostly on the moon’s near side won’t be buried under debris, keeping older rocks from 4 billion plus years ago exposed for collection by moonwalkers. These older rocks can help shed light not only on the moon’s origins, but also Earth’s.

Kring said it’s unclear whether these two canyons are permanently shadowed like some of the craters at the moon’s south pole. “That is something that we’re clearly going to be reexamining,” he said.

Permanently shadowed areas at the bottom of the moon are thought to hold considerable ice, which could be turned into rocket fuel and drinking water by future moonwalkers.

NASA’s Artemis program, the successor to Apollo, aims to return astronauts to the moon this decade. The plan is to send astronauts around the moon next year, followed a year or so later by the first lunar touchdown by astronauts since Apollo.

The Associated Press Health and Science Department receives support from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Science and Educational Media Group and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The AP is solely responsible for all content.