Chris Maurer of Redhouse Studio is working with NASA Ames scientists to revolutionize how we house ourselves in space, using “bio-bricks,” a fusion of fungi mycelium and plant waste.

To build a home on Earth, it’s simple: Call Home Depot and schedule a delivery.

Shipping wood, metal and glass to Mars – millions of miles away, reachable only by spacecraft — is much tougher.

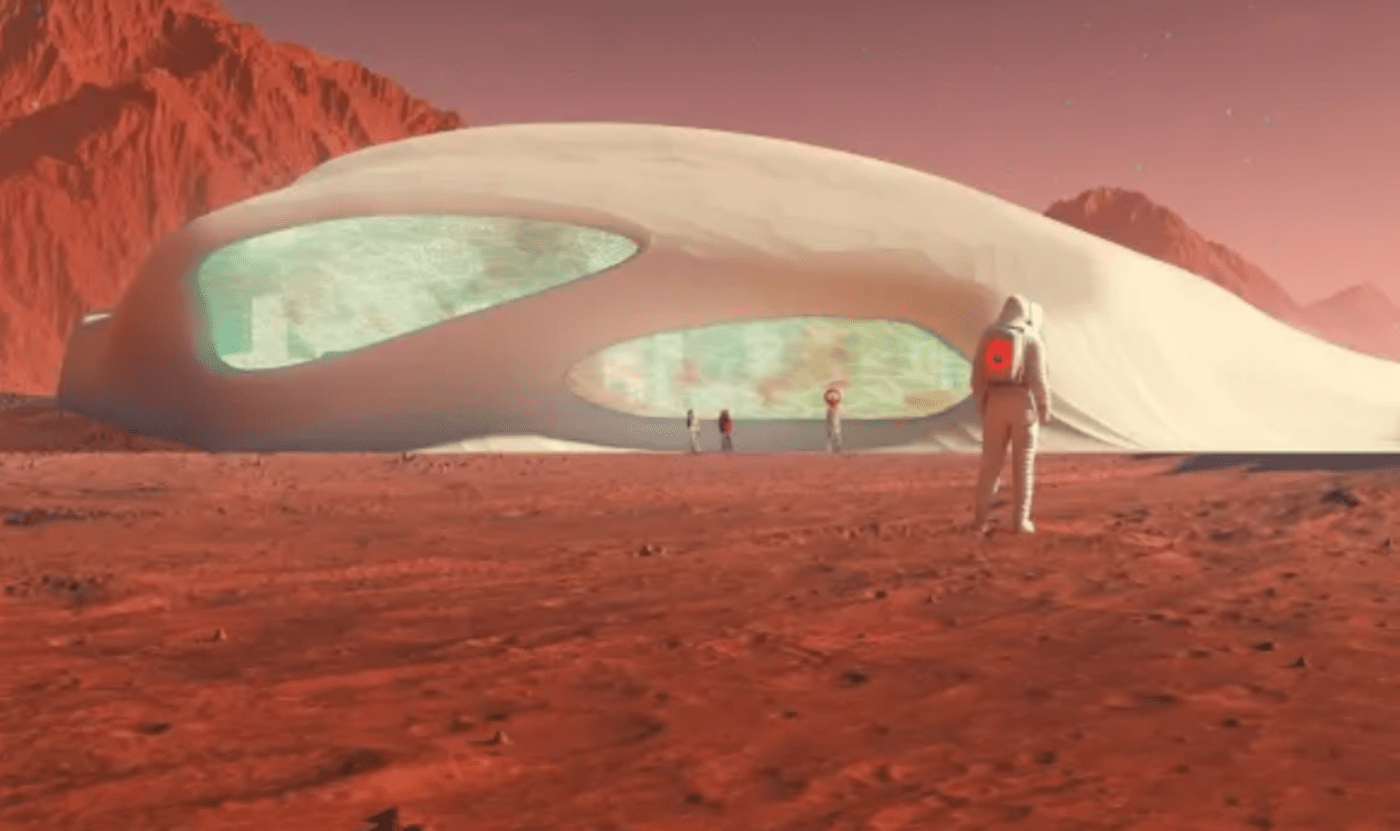

A team at NASA Ames Research Center has a proposed solution: “mycotecture,” the creation of construction material using the fungal strands of mushrooms.

If shipped as tiny spores, NASA hopes the fungus could grow our future Martian homes – without pricey delivery charges.

“Right now, traditional habitat designs for Mars are like a turtle carrying our homes with us on our backs,” said principal investigator Lynn Rothschild, whose team will be given $2 million over two years to advance the concept. “It’s 100% reliable, but you’re spending a huge amount of energy carrying it around.”

In ice cube trays in a windowless lab, Rothschild is growing fungus to test its resilience to the extreme conditions of space, such as intense heat and bone-chilling cold. Colleague Maikel Rheinstadter of Canada’s McMaster University is subjecting it to micro-gravity and deadly ionizing radiation.

The goal is to create a product, like particle board, that can be manipulated to build homes, garages, sheds and furniture used not just by astronauts but, someday, ordinary citizens as well. NASA’s Artemis campaign aims to send people to the Moon in 2026. Living on Mars isn’t far behind.

“As NASA prepares to explore farther into the cosmos than ever before, it will require new science and technology that doesn’t yet exist,” said NASA Administrator Bill Nelson, in a written statement. “This new research is a steppingstone to our Artemis campaign as we prepare to go back to the Moon to live, to learn, to invent, to create – then venture to Mars and beyond.”

Life in a space capsule is too confining. Apollo 11’s lunar module that in 1969 briefly landed astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin on the moon was the size of prisoners’ Cell Block C at Alcatraz Federal Penitentiary.

On Earth, we can simply book an Airbnb or couch-surf with friends. On Mars, however, our fate is much more bleak: death by freezing, carbon dioxide poisoning, radiation exposure or getting sucked into space by a huge dust devil.

There’s no dialing 911. And the red planet is indifferent to our suffering.

But home construction on the Moon or Mars is daunting.

“When we go off planet Earth, we’ve got a huge, huge problem — and that is ” ‘upmass,’ ” the cost of transporting cargo in space, Rothschild said.

When building at home or work, “I don’t care if something weighs 300 pounds. But there are ‘launch costs’ in getting something that’s heavy out of Earth’s gravity. Can I take that 300-pound piece of equipment and get it down to, maybe, 30 ounces?”

“Life,” which starts as a tiny cell, seed or spore, “can solve this ‘upmass’ problem,” she said.

A common fungus, a red-colored species called Ganoderma lucidum, seem to offer the most practical strategy for the project, called Mycotecture Off Planet. The fungus is native to parts of Europe and China, where it grows on decaying hardwood trees.

Bricks produced using mycelium, yard waste and wood chips as a part of the myco-architecture project. Similar materials could be used to build habitats on the Moon or Mars.

Shipped as dormant spores in a compact habitat, it would start growing after being nourished by water and a diet of algae, rehydrated wood chips or nutrient broth.

If mixed with regolith, the loose rock and dust that sits on the surface of the moon and Mars, it could become a sturdy structure.

The fungal mycelia, the millions of underground threads that comprise the root structure of fungi, fill whatever space they’re given, Rothschild said.

They would adopt the shape of a pre-designed inflatable frame, like a balloon. “They don’t care if they’re growing into the structure of a house, or a table or a chair,” she said.

The frame also would contain the fungal growth to prevent contamination of the Martian environment. Escaped fungi could devastate other species.

“If there were another life form on Mars, it would be the greatest tragedy if we destroyed it,” said Rothschild.

Fungus has been coaxed into making other materials, like imitation leather. The Emeryville company MycoWorks is creating a material called Reishi, after the Japanese name for the genus of mushrooms, that has the look and feel of leather but is free of animal parts. Bolt Threads, based in Berkeley, also is producing a leather-like material made from fungal mycelium.

There are challenges, because fungus requires some nurturing. When it’s too cold, growth slows. When it’s too hot, it turns into dust. To fend off radiation damage, the fungus would be bioengineered to contain the protective pigment called melanin, the disgusting black gunk that grows inside dishwashers and other dark moist surfaces.

Once it survives tough testing, the fungus will be sent to the Stanford University lab of Debbie Senesky for mechanical evaluation. That team will ask: Did the harsh Martian conditions change its physical resiliency?

NASA is also working with Cleveland-based architect and mycologist Chris Maurer of Redhouse Studio. Maurer and his partners are working to revolutionize how we house ourselves — not with bricks and mortar but with “bio-bricks,” a fusion of fungi mycelium and plant waste.

A stool constructed out of mycelia after two weeks of growth. The next step is a baking process process that leads to a clean and functional piece of furniture. Credits: 2018 Stanford-Brown-RISD iGEM Team

“There are no building codes for the Moon and Mars right now,” said Rothschild.

The fungus could create a structure within several weeks, she said. To save time, NASA might start construction during a quick initial visit, so work is wrapped up by the time astronauts arrive.

If successful, the fungus could even offer edible mushrooms.

“Wouldn’t it be cool,” said Rothschild, “to have a table that is producing your dinner?”