From the day the first primitive human clambered up a tree while fleeing a pack of ravenous wolves — and later grunted out the details of their narrow escape to cave dwellers around a campfire — the human brain appears to have been hard-wired to process and retain stories.

Now, a research team at the Johns Hopkins University is asking for the public’s help in mapping the areas of the brain that kick into high gear every time we read a new Stephen King novel or see a “Deadpool” sequel, or watch reruns of “Doctor Who.”

It turns out that telling and listening to tales isn’t just fun — it’s a key survival strategy.

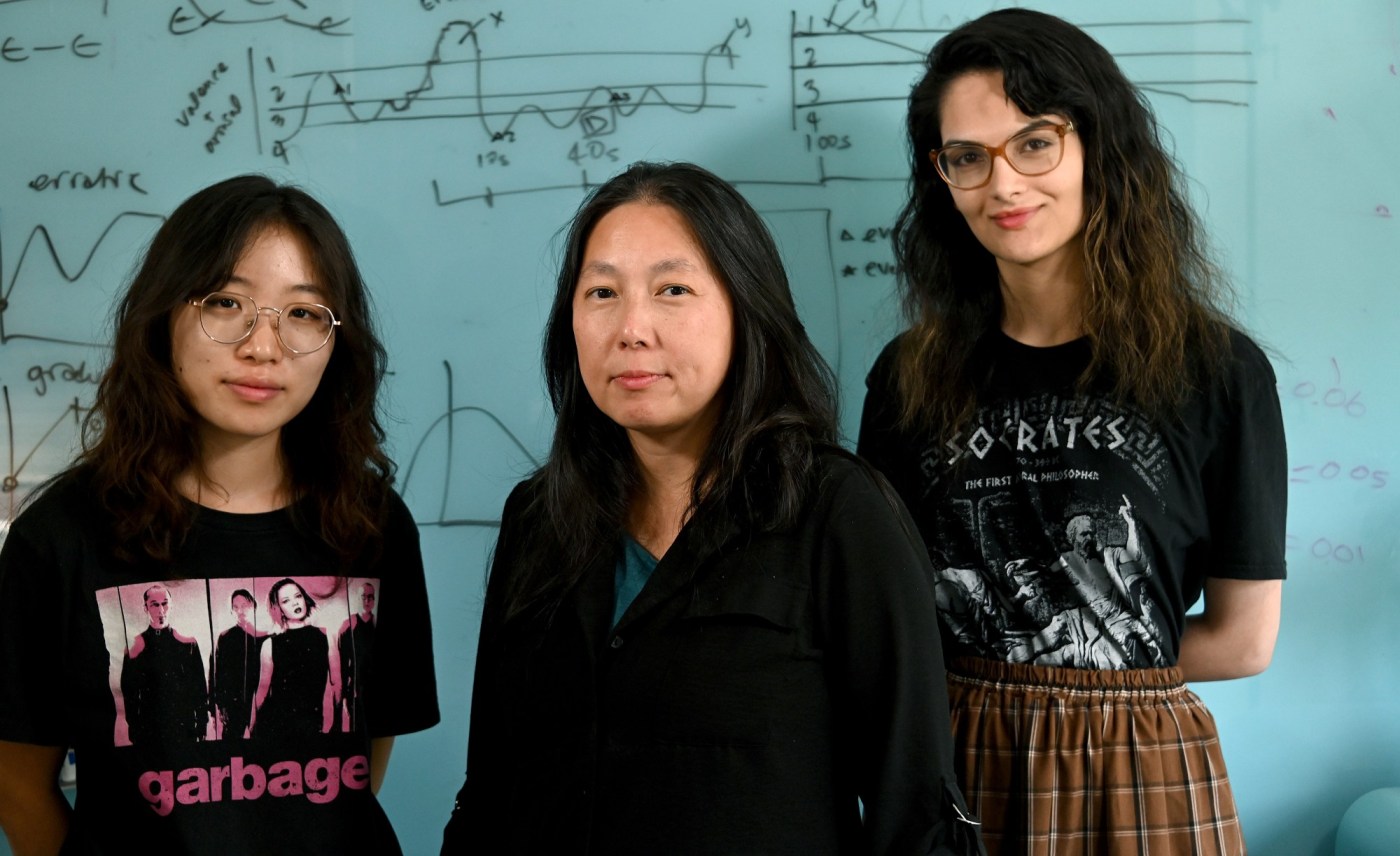

“Understanding stories is part of the fundamental anatomy of the brain,” said Janice Chen, an assistant professor of psychological and brain sciences at Johns Hopkins, “and it’s a very robust brain system that you find in everyone.”

Chen said different regions of the brain tune into characters or location, while others are devoted to what could be described as the plot.

“If you think about it, your life is made up of a series of events. And each one of those events is a story,” she said.

But Chen doesn’t study literature. She studies how neural systems support memory. And she’s especially interested in a group of high-level brain regions, known as the “default mode network,” that appear to be involved in episodic memories, or those that spring from personal experience.

Many of her experiments involve putting subjects into an “fMRI” — a functional magnetic resonance imaging machine — and recording their brain activity as they read a book, watch a movie or talk about an episode of a favorite TV show.

Chen thought members of the public might enjoy helping to design her team’s research studies. How often does the average Baltimorean get a chance to don an imaginary white lab coat, to become Doctor You?

So she reached out to her colleague, Dora Malech, an associate professor in Hopkins’ Writing Seminars and editor in chief of The Hopkins Review literary journal, and asked for her help in devising a short story contest.

The fMRI Writing Prize contest, which runs through July 31, is for a piece of original, unpublished “flash fiction” or a very short story of between about 500 and 1,500 words. It is open to high school students and adults who live, work or study in Baltimore.

“We thought it would be an accessible way to engage the public in science experiments taking place at Hopkins,” Malech said. “There are overlapping questions about what makes enduring art and how art affects memory.”

Two winners — one aged 14 to 18, and one adult — will be selected to receive a $500 prize based on standard literary criteria as well as whether their work contains attributes useful to the researchers.

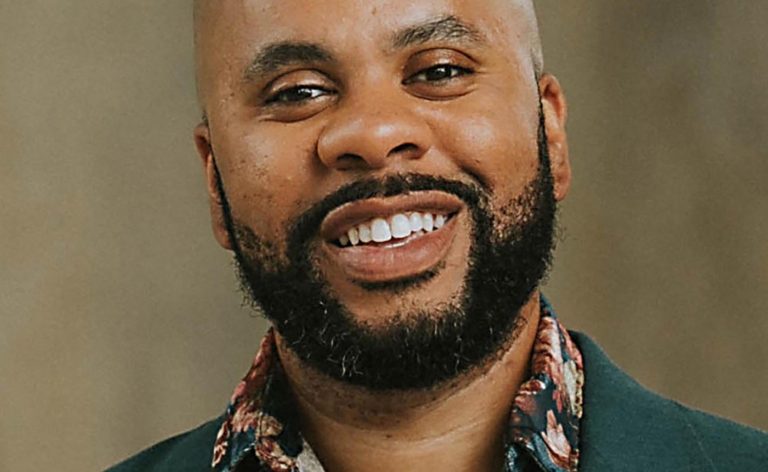

Chen, for instance, is interested in stories that have unusual narrative structures instead of unfolding chronologically. Sammy Tavasoli, who is studying for her doctorate in brain sciences, is intrigued by memories of emotional events, while scientist Christopher Honey is looking into why some stories linger in the brain for weeks or months after the reader has turned the last page.

The winning stories will be published in the Hopkins Review. Their authors also will receive a tour of the lab where the research is being conducted, plus a framed computer image showing the brain activity of study participants as they read the winning submissions.

Iris Lee, who has worked in Chen’s lab and who will begin graduate school in creative writing this fall, said that because the material collected in the contest will be used for a variety of studies, researchers aren’t looking for any particular type of story. A whodunit is as likely to win as a historical romance.

“Authors can experiment with plot,” she said. “They can experiment with time and write stories that cross generations and that show how the past and future affect one another.”

The winning submissions will be used in experiments exploring the link between narrative and memory, a relationship that helped our species persist from one generation to the next. If our early human couldn’t remember how they escaped the wolves, they might not think to climb a tree the next time. They couldn’t show their friends the hidden stream they found stocked with fat fish.

“If you don’t have a memory, you don’t the ability to go from one moment to the next and predict what’s going to happen,” Chen said. “You can’t connect cause and effect. Memory is essential to being a person.”

And stories have proven particularly suited for helping people remember better.

“There’s decades-old studies that show that if you just give people a list of random words to read and then ask them to recall it, they’re not very good at it,” Chen said.

“But if you force them to create a story out of that same list of words, their memory goes through the roof.”

She said stories across all formats are equally useful at transforming fleeting events into permanent memories, whether from written words, song lyrics played over the radio, or a sequence of images flashed onto screens.

And if at times it seems our need for narrative is insatiable, it’s because our brains are trying to motivate us to consume stories. Like other activities necessary for survival from eating food to having sex, we’re programmed to crave them.

That’s why the Hopkins researchers are asking for Baltimoreans’ help in generating new and original tales. It’s possible, they said, that researchers eventually will learn enough about memory to gain insight into the causes of some of humanity’s most intractable problems, from schizophrenia to Alzheimer’s disease to other forms of age-related memory loss.

“There’s a lot of questions you can ask about memory using the same data,” Chen said.

“This contest is really a two-way street,” she said. “We’re going to see what stories come in, and use them as a source of inspiration for thinking of interesting questions that we can try to answer.”