Less than a month after the U.S. Supreme Court gave cities broader authority to police homelessness, a federal judge has halted Oakland’s plan to clear a small encampment near the Bay Bridge — a win for homeless advocates in an early test of local officials’ power to carry out sweeps in the wake of the high court’s landmark ruling.

On Wednesday, the judge in the case ordered the city to hold off clearing the camp at Toll Plaza Beach — a hidden stretch of shoreline just off Highway 80 with panoramic views of the bay — until at least Thursday, July 18.

Encampment residents say Oakland officials failed to offer the dozen or so people living there appropriate shelter or housing to accommodate their various disabilities ahead of the planned eviction. In court filings, they said a sweep would be “devastating — potentially causing injury or death.”

In what could provide a template for future encampment showdowns, camp residents allege that city officials violated the federal Americans with Disabilities Act by not helping them find suitable housing or temporary shelter before proceeding to clear the camp.

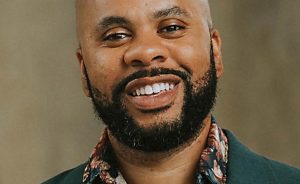

“They’re trying to intimidate us to get out of here, but it’s like, where would we go?” said camp resident Michael Avery, who’s HIV-positive and living out of a maroon-colored minivan at the far end of the dirt road to the windswept beach.

The judge gave the city until Monday to respond to residents’ claims. On Tuesday, the court will consider plaintiffs’ request for a more permanent order suspending the sweep.

Michael Avery rubs his dog, Girl, at the small homeless encampment adjacent to the foot of the Bay Bridge in Oakland, Calif., on Friday, July 12, 2024. (Ray Chavez/Bay Area News Group)

Across the Bay Area in recent years, homeless people have successfully sued to delay numerous encampment closures until cities could offer shelter to camp residents, including sweeps of hundreds of people from San Jose’s Columbus Park and Wood Street in West Oakland.

Those cases relied primarily on lower-court rulings that determined punishing people for sleeping on public property without providing “adequate shelter” violated the Eighth Amendment’s ban on cruel and unusual punishment. But last month, to the cheers of some local officials under increasing pressure to deal with encampments, the Supreme Court’s conservative majority agreed to strike down that precedent.

Now, homeless people must resort to other legal arguments if they hope to halt sweeps. And some advocates say the Oakland case could provide a blueprint.

“We just have to really go through the law and argue it, and we’re not afraid of that,” said Andrea Henson, a civil rights attorney for the plaintiffs who has also represented homeless people throughout the Bay Area.

Residents of the Oakland camp maintain that moving into emergency group shelters with limited accommodations for their disabilities doesn’t satisfy the requirements of the Americans with Disabilities Act.

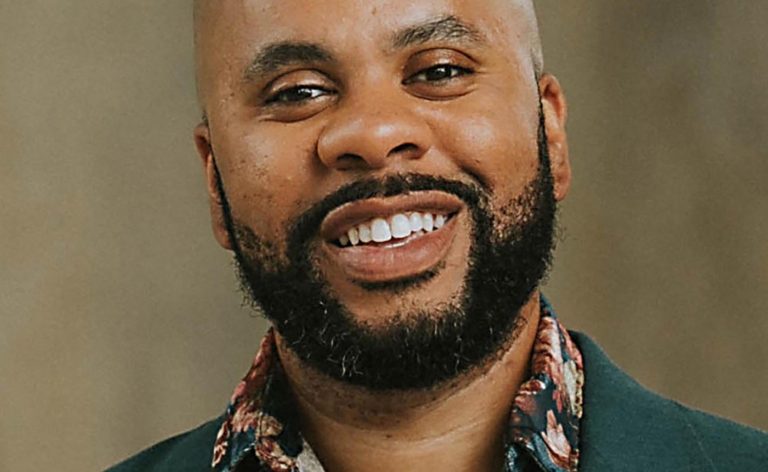

Frank Ernst, a plaintiff in the case, said he has PTSD and an anxiety disorder from childhood trauma, making it impossible to stay in close quarters with strangers at a shelter. “It feels more like you’d be in prison,” he said.

Residents also argue the planned sweep would breach a settlement the city reached in 2018 that prevents disbanding encampments during a heat wave. Oakland temperatures reached the high 90s last week. They say being pushed out now would infringe on their right to due process and protection from a “state-created danger.”

While those claims may not be as thoroughly tested in court, advocates in the Bay Area are confident judges will be sympathetic to such arguments in this case and future lawsuits.

Tristia Bauman, an attorney with the Law Foundation of Silicon Valley, said the recent Supreme Court decision “does not give governments a green light to criminalize homelessness.”

Frank Ernst shows a federal court document that grants a temporary stay through July 18 at the small homeless encampment adjacent to the foot of the Bay Bridge in Oakland, Calif., on Friday, July 12, 20224. The City of Oakland was supposed to clear the encampment from July 9 to 11. (Ray Chavez/Bay Area News Group)

“The way sweeps are done and the harms they cause to people who are displaced implicates many legal protections,” she said.

In its initial court filings, Oakland said its outreach teams followed the city’s encampment management policy to offer shelter to everyone and “accommodate as many unique circumstances (including self-identified disabilities) as possible.” Three camp residents told this news organization they hadn’t been offered a bed.

Moreover, the city argued the San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission has determined allowing the camp to persist would violate state environmental law and is threatening daily fines if it isn’t cleared soon.

The city declined to comment on the case.

The repercussions of the Supreme Court’s decision are also playing out in San Francisco, where a federal appeals court cited the ruling in its move to lift an injunction that partially restricted how the city could clear encampments.

Still, advocates in that case vowed to keep fighting, signaling they would continue making similar arguments as in the Oakland case to ensure San Francisco provides adequate accommodations for people with disabilities before closing camps.

Berkeley, meanwhile, is considering a resolution to prevent officials from enforcing new penalties on homeless people following the landmark ruling, even as the city has recently fought lawsuits aiming to halt sweeps.

Well before the high court’s decision shifted the legal landscape concerning homelessness, a group of local kite surfers had been clamoring for Oakland to clear Toll Plaza Beach.

Related Articles

Kneaded culinary academy cooks up solutions for struggling South Bay youth

Pasquale Esposito performs July 12 benefit for Family Supportive Housing

Water district delays vote on law to remove homeless encampments from creeks in San Jose, Santa Clara County

Chemerinsky: Supreme Court’s purely ideological reasoning will change our lives

Bay Area receives $14 million from state to combat youth homelessness

In a post on its website, the San Francisco Boardsailing Association wrote that one of the “best secret spots for kiting” has for years now been an “epicenter” for car break-ins while “increased trash and direct sewage runoff” continue to pollute the bay.

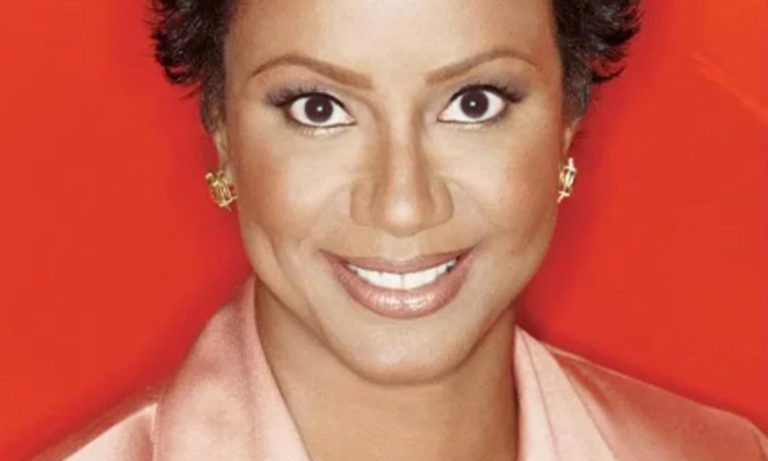

Ernst, who lives at the beach in a makeshift wooden shack, complete with a jury-rigged shower and solar-powered string lights, disputed that characterization, instead describing the camp as a close-knit community away from the chaos of other larger encampments.

Still, Ernst, who’s been homeless for the past eight years, said he would accept permanent housing if offered. But ultimately, he just hopes the city gives him more time to pack his belongings and possibly help store them before clearing everyone out.

“I’m a realist,” Lewis said. “I understand that Oakland is Oakland. I just wish people had some heart here.”

View of a vehicle and other belongings of a homeless person living at the small homeless encampment adjacent to the foot of the Bay Bridge in Oakland, Calif., on Friday, July 12, 2024. (Ray Chavez/Bay Area News Group)