“There is a patch of land where nothing grows,” Greg Sarris writes in “A Man Learns to Smell Flowers,” one of the stories in his new book, “Forgetters.”

The Coast Miwok and Southern Pomo Indians believe this flat, dry expanse along the road between Freestone and Bodega Bay was once was covered by a lush meadow of clover. They called it “a beautiful place.”

In this story and others, the Santa Rosa-born writer, academic and tribal leader explores familiar themes: the Native American experience in Sonoma and Marin counties, centering on characters who struggle with losing their connection to the land of their ancestors. As Sarris says, the land is the “sacred text” through which Native Americans find their sense of history, community and personal identity.

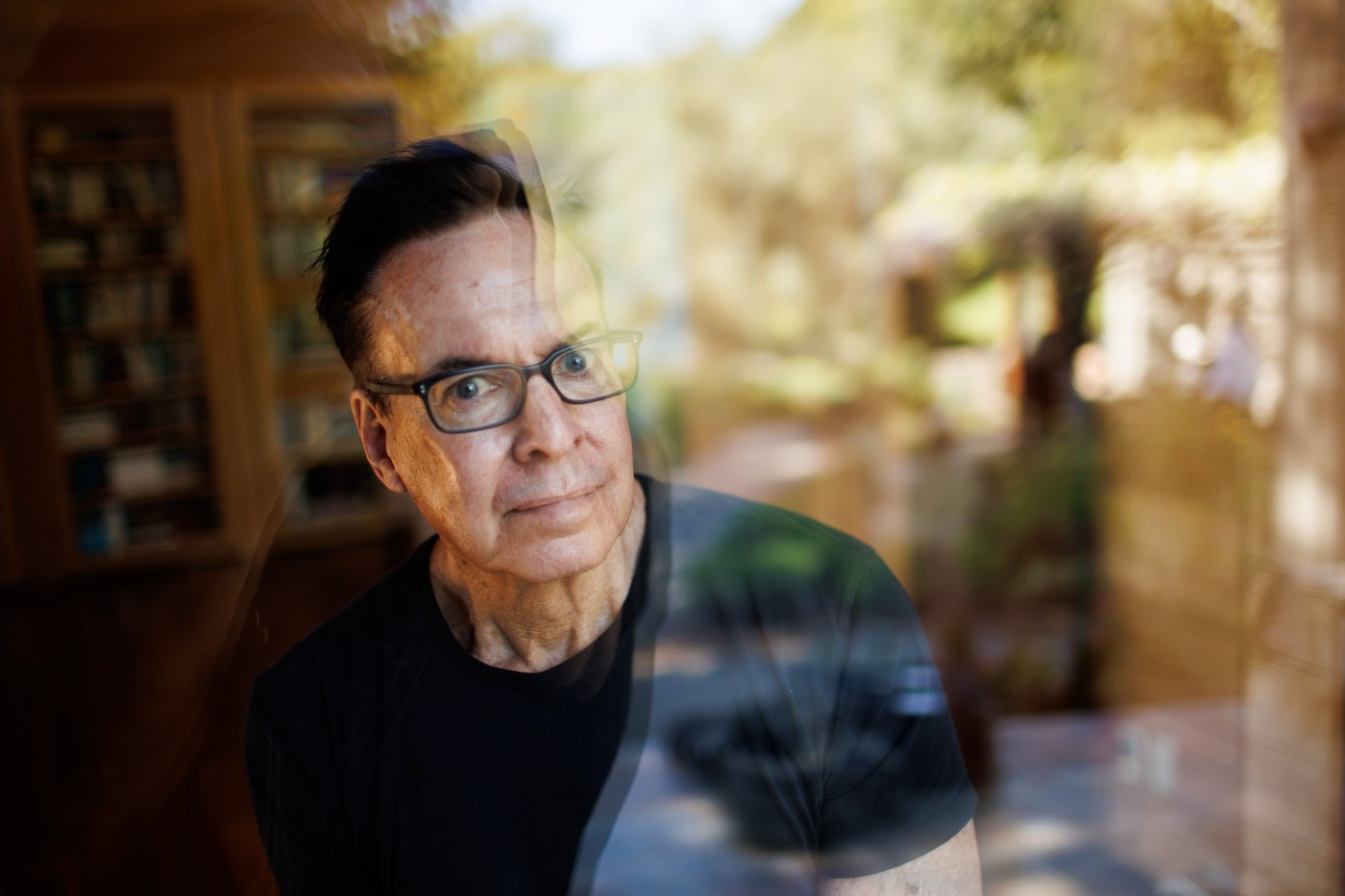

Author Greg Sarris during an interview at his home in Penngrove, Calif., on April 30, 2024. (Dai Sugano/Bay Area News Group)

As a writer, Sarris is best known for fiction and nonfiction set in the North Bay, including a1994 story collection, “Grand Avenue,” that was adapted into an HBO miniseries. He retired in 2022 from Sonoma State University, where he taught creative writing and American Indian studies. But he’s also kept busy over the past 30 years leading the Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria, who operate the luxury Graton Resort and Casino in Rohnert Park, one of the largest Indian casinos in California.

There are aspects of “Forgetters,” told in the classic style of Coast Miwok and Southern Pomo creation stories, that also resonate with Sarris’ dramatic personal journey to reconnect with family and community. He grew up in Santa Rosa and never knew his birth parents. Years later, he embarked on a search for his heritage, discovering the tragic circumstances of his 1952 birth but also finding a sense of home with the Native American people he befriended during his youth in Sonoma County.

Author Greg Sarris’ latest book “The Forgetters.” Photographed at his home in Penngrove, Calif., on April 30, 2024. (Dai Sugano/Bay Area News Group)

“It’s like a Moses story,” Sarris said half-jokingly about how he, too, was set adrift as a baby, but found his way back to his people. And, like Moses, Sarris became his people’s leader.

The 72-year-old Sarris lives on Sonoma Mountain, where Coyote decided to create the world, with a view towards the Pacific Ocean and territory that was once home to some 20,000 Coast Miwok and Southern Pomo people.

Sitting on his deck in the shade of bay laurels, Sarris explained that each story in “Forgetters” opens with descriptions of specific places in Sonoma and Marin counties and Indian villages and other landmarks wiped out by European and American colonization or 20th-century development.

“An outcropping of rocks or a grove of trees, a creek or a small pond or lake, they all had stories associated with them,” he said. “We knew ourselves and how we were home from our stories.”

In “Forgetters,” a pair of crows, said to be Coyote’s twin granddaughers, introduce each timeless story from their perch atop Gravity Hill. In one, a troubled man hopes an osprey will lead him to gold at the mouth of the Russian River. In another, a woman loses her lover but reconnects with her family as she performs fairy tale-like tasks in the Laguna de Santa Rosa wetlands near Sebastopol.

“A Man Learns to Smell Flowers” is set in the 1870s, after tribal populations have been decimated. The remaining Indians, “long separated from their ancient villages … (are) at the mercy of American landowners for work and a place to live.” The protagonist, Kaloopis — Coast Miwok for hummingbird — works for one of these landowners on that patch of land near Freestone, tending the garden next to their magnificent Victorian. Like Sarris, Kaloopis is a gifted storyteller, entertaining the children of one of the other Indian workers — one way he helps create a sense of community among this small band of displaced people.

But this community is fragile. Kaloopis’ favored status at the farm breeds resentment, and suspicions grow over his origins. Maybe he’s a “walepú,” a shape-shifter who will put a curse on them. Kaloopis is eventually shunned, and the garden and surrounding land become “gray and lifeless.”

Sarris said the story is about “the dangers of people speculating about things they don’t know.” Given Sarris’ prominent position in his tribe, he has also been the target of speculation, including about his heritage. He said the “confusion” about his adoption and Native American identity grew heated when the tribe was seeking support to build its casino, which opened in 2013. One critic was a relative who denied the family was Native American.

As he talked, Sarris shared photos of his Coast Miwok and Southern Pomo relatives and referred to tribal genealogical records that show he’s descended from Tom Smith, a Miwok medicine man who was born near Fort Ross in 1838 and fathered as many as 20 children, including Sarris’ great-great grandmother.

“My blood family comprises a third of this tribe, for which I’ve served as the chairman for over 30 years,” he said.

Sarris didn’t know about these blood ties when he grew up, feeling alienated in the Santa Rosa home of his white adoptive parents. At around age 12, he found refuge with Mexican and Native American friends in the poorer parts of Santa Rosa and met two women who were traditional Native American healers and renowned basket weavers. One was Mabel McKay, who delighted him with her “old-time” Native stories about Coyote and creation.

“Because I didn’t quite know where I belonged, I would always listen, especially to old people as they told their stories,” Sarris said.

With their support, Sarris focused on school, attending Santa Rosa Junior College before transferring to UCLA as an English major. As McKay’s stories continued to play in his head, he began writing them down and then launched an academic career that took him to UC Santa Cruz and professorships at UCLA and Loyola Marymount.

Even as his career flourished, Sarris felt adrift over his origins. He eventually learned that his birth mother was Bunny Hartman, a 16-year-old high school junior from Laguna Beach, whose father was a department store executive. Bunny’s mother brought her daughter to Santa Rosa to give birth and relinquish her baby in a closed adoption. Tragically, Bunny died several days after Sarris’ birth from a botched blood transfusion.

Sarris interviewed Bunny’s brother and girlfriends and finally concluded that his birth father was Emilio Hilario, a former Laguna Beach High School football star and a professional boxer. Sarris never got the chance to meet Emilio, who died in 1983 at age 52, but Sarris was welcomed into the Hilario family. In a fantastical coincidence, Sarris learned that Emilio’s mother came from a Native American family near Santa Rosa, so Sarris was potentially related to people who already felt like kin.

After Sarris reconnected with the Coast Miwok and Southern Pomo in Sonoma County, the tribal elders invited the then-UCLA professor to help unite the scattered families. In 2000, President Bill Clinton signed a bill restoring federal recognition to the Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria and provided a way for the long-landless tribe to eventually have a reservation. Since then, the casino has opened, and the tribe’s numbers have rebounded to more than 1,500.

In April, Sarris published “The Forgetters,” whose tales remind us of what is lost when people are disconnected from the land or each other. “The stories connect with one another, just as the animals and plants and all other things on Sonoma Mountain do,” Sarris writes. “This is one of the many important lessons the stories teach: that since the beginning of time, all of life is one family.”