Two California laws aimed at protecting children from the dangers of social media are receiving fierce pushback from tech industry lobbyists, who are urging Gov. Gavin Newsom to veto the bills on the grounds that they are “constitutionally flawed.”

This week the Chamber of Progress, a trade group funded by tech giants including Meta, Google and X, outlined their concerns in a scathing letter to Newsom.

The two bills under attack are AB 3172, which would hold social media companies financially liable for harm caused to minors, and SB 976, which would ban the use of addictive algorithms.

“Passing unconstitutional bills will lead to years of litigation with a predetermined outcome: they will be enjoined and then set aside by the courts. None of which does anything to protect young people online,” wrote Todd O’Boyle, senior director of technology policy at the Chamber of Progress. “We urge you to veto SB 976, AB 3172, or other similarly-flawed bills that reach your desk.”

Assemblymember Josh Lowenthal, D-Long Beach, who authored AB 3172, called the letter “the ultimate form of flattery,” noting that it is unusual for lobbyists to make a direct appeal to the governor before laws have even been passed.

Both AB 3172 and SB 976 cleared their house of origin with bipartisan support and are on track to be passed once the state legislature resumes meeting in August. During previous hearings the Chamber of Progress and other tech industry groups such as TechNet and NetChoice vociferously opposed the bill.

“They have no ability to block it in the legislature,” Lowenthal said of the tech industry groups, “so they’re trying to go directly to the governor right now using scare tactics. I don’t think it’s going to work.”

Lowenthal said he has not yet discussed his bill with the governor, but he is ” very optimistic” that Newsom will sign it based on his track record of supporting child wellness and development.

If passed, AB 3172 would impose financial liabilities on large social media companies if a court finds that they knowingly offered products or design features that resulted in harm to minors. The bill would apply to platforms with more than $100 million in annual profits and would allow courts to impose financial damages ranging from a set $5,000 per violation, up to $1 million per child.

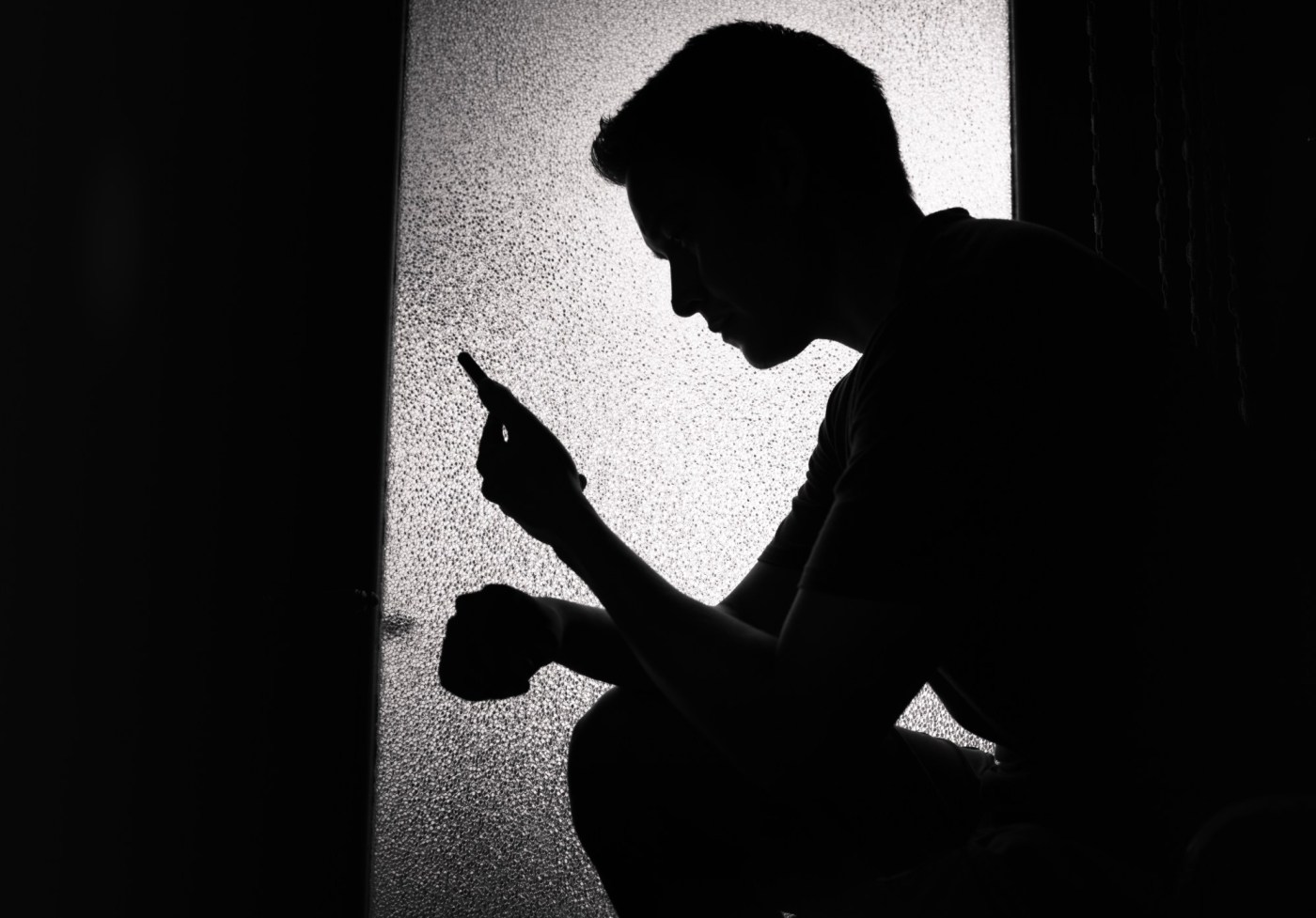

“The truth of matter is that the mental health of young people is in the toilet,” said Lowenthal. “Suicide rates for youth are up 62% since 2011, eating disorders, anxiety and depression are off the charts. We are in a crisis and we’re requiring that these companies take responsibility for that.”

The Chamber of Progress criticized the bill for failing to provide a clear definition of what constitutes harm to a minor, saying it contains “overly broad language that controls the speech of private actors while providing little to no guidance on how to comply.”

The group also said the bill violates minors’ First Amendment right to access information because it will force social media companies to excessively moderate their content to avoid financial penalties in court.

Michael Karanicolas, executive director of the Institute for Technology, Law and Policy at UCLA, said Newsom should not veto the bills purely because of the threat of First Amendment lawsuits. He said that neither AB 1372 or SB 976 strike him as “manifestly unconstitutional,” but he noted that government regulation of social media is a new legal frontier.

“I think the murkiness around the applicability of the First Amendment in this area is not a reason not to sign it, because this area of law is unsettled and it’s always going to be unsettled until a case gets pushed through,” he said.

However, Karanicolas does believe the vagueness of the bill could be an issue.

“I think it’s absolutely a legitimate critique that this law seems to open the door to very heavy penalties without a lot of clarity on what will trigger those penalties or what appropriate standards of behavior we should expect from platforms,” he said.

When considering a potential veto, Karanicolas said Newsom should weigh how the bill will affect children’s ability to express themselves online versus how effectively it will improve complex issues such as youth depression and anxiety.

“Is this going to significantly move the needle on child safety or is it just creating a large and difficult to track pool of liability that’s essentially going to be a gift to lawyers?” Karanicolas said.

Lowenthal defended the vagueness of the bill, saying that it gives social media companies the freedom to determine the best ways to alter product to protect children.

He said this legal push is needed to incentivize new safety policies such as stringent age restrictions on inappropriate content — or otherwise companies won’t voluntarily make changes that could prompt users to move to another platform.

“What we’re trying to create is a framework that gives parents and stakeholders comfort to have their children online and know that there are release valves when harm has been created,” said Lowenthal, “so that these companies can be more successful, they can step on the gas (in making safety improvements) and we can all be aligned in our incentives to protect children.”

Related Articles

The way to voters’ hearts? It must be memes and TikTok, influencers say

5 Bay Area-based #BookTok and Bookstagrammers to follow — and what they’re reading right now

E-commerce pioneer Grubhub celebrates 20 years of delivering dinner to your door

Elon Musk says he’s moving SpaceX and X headquarters from California to Texas

Who is Ingrid Andress? Country singer says she was drunk during Home Run Derby national anthem

The second bill being targeted by the tech industry, SB 976, is authored by state Sen. Nancy Skinner, D-Oakland.

Her bill would ban social media companies from sending minors an addictive feed or notifications during the school day or overnight without consent of a parent or guardian. Under the bill, youth would not automatically receive a curated feed designed to maximize their attention, but instead a linear feed showing the content in the order it was posted.

“Social media companies have designed their platforms to addict users, especially our kids,” said Skinner in a statement on the bill. “Studies show that once a young person has a social media addiction, they experience higher rates of depression, anxiety, and low self-esteem, but social media companies have been unwilling to voluntarily change their practices.”

In its letter to Newsom, the Chamber of Progress argues that recent Supreme Court decisions upheld social media platforms’ right to algorithmically curate the content. The letter cites a majority opinion authored by Justice Elena Kagan in NetChoice v. Paxton saying “to the extent that social media platforms create expressive products, they receive the First Amendment’s protection.”

Karanicolas said that while this case does, for example, uphold the platforms’ right to curate which content appears on a homepage, it does not clearly define expressive content and therefore what aspects of social media are subject to First Amendment protection.

“You get into these very complicated questions about whether or not the behavior that’s being regulated is expressive, especially when most of the time it’s not a human who’s actually doing the work on this stuff. It’s usually algorithms.”

Both AB 3172 and SB 976 are venturing into uncharted territory when it comes to regulating social media, Karanicolas said.

Lowenthal says that’s exactly why it’s so important to move the legislation forward and establish California as a leader in protecting children online.

“These bills are groundbreaking; there isn’t anything that exists close to them whatsoever and California is the most appropriate place for this to be taking place,” he said. “We’re the most populous state and most of these tech companies are actually located in our state.”