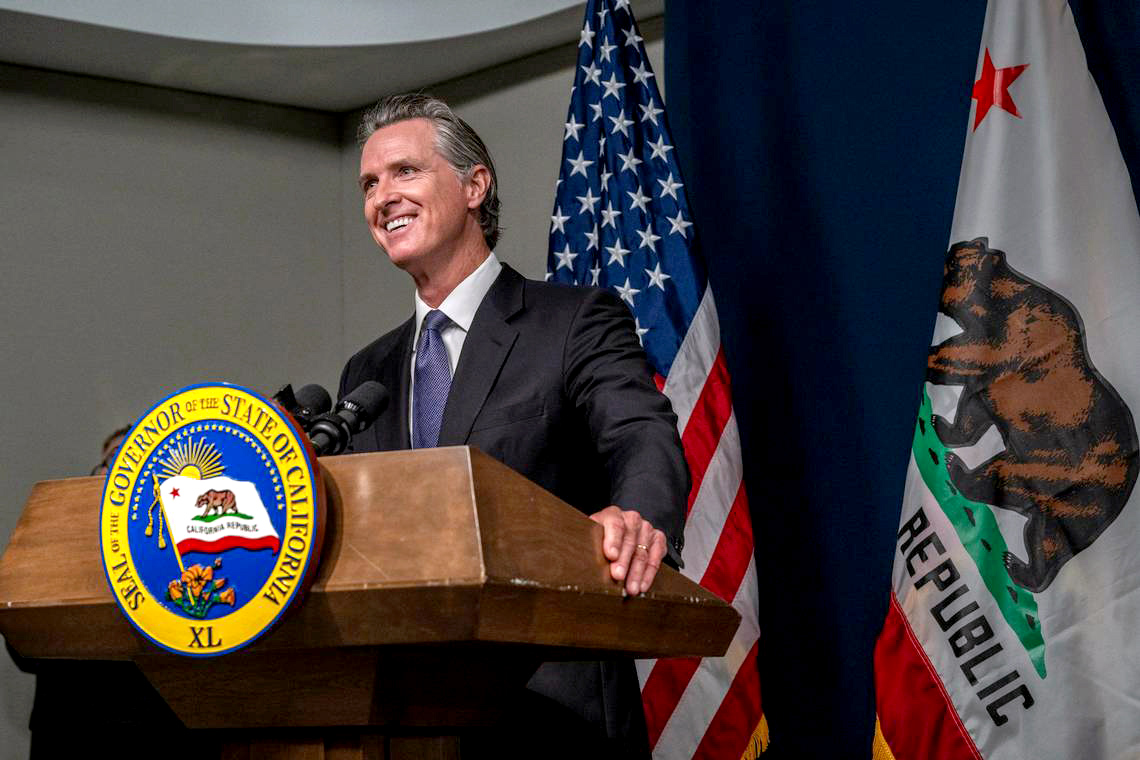

Gov. Gavin Newsom has devoted much of his second term to building a national political profile and more or less succeeded.

Why he did is less evident. He says he was helping his Democratic Party become more aggressive. National media assumed he was laying the groundwork for a presidential campaign. Or it might have been just an ego trip.

Newsom still has 28 months as governor, and the question is whether he will now pay more attention to his day job or, for whatever reason, continue his quest for relevance on the national stage.

Truth is, were Newsom’s governorship to end now his record of accomplishment would be scant, particularly if measured against that of his immediate predecessor, Jerry Brown.

Brown firmed up the state’s shaky finances, overhauled school finance, addressed overcrowding in prisons and persuaded the Legislature to reform the workers’ compensation program and public employee pensions.

Newsom promised much when he was seeking the office six years ago, claiming to be a student of governance who could deliver transformative change, such as a single-payer health care system and millions of new housing units to solve one of the state’s knottiest problems.

“I’m tired of politicians saying they support single-payer but that it’s too soon, too expensive or someone else’s problem,” Newsom said during the 2018 campaign, winning the support of advocates. After the election, however, Newsom backed away, citing the difficulties of merging multiple systems and terming his pledge “aspirational.”

Newsom has extended Medi-Cal, California’s health care program for the poor, to millions of additional Californians, including undocumented immigrants, and he can claim more or less universal coverage. However, its costs are massive, while the state budget is plagued by red ink, and poor Californians still struggle to find medical providers.

“As governor, I will lead the effort to develop the 3.5 million new housing units we need by 2025 because our solutions must be as bold as the problem is big,” then-Lt. Gov. Newsom wrote in 2017. During his inaugural speech in 2019, he went even further, announcing a “Marshall Plan for affordable housing.”

While Newsom has signed multiple bills meant to erase roadblocks to construction and he cracked down on communities that impede development, housing construction has not markedly increased and the shortage has continued to grow.

Housing is not California’s only societal basic that’s lacking. Others include a dependable water supply, adequate electrical power — not only to meet current demand but the immense amounts that a carbon-free economy would require — and a truly embarrassing deficit in reading and other academic skills vis-a-vis other states.

Newsom has championed pre-kindergarten education to improve the latter but the jury is still out on its efficacy. The same uncertainty about outcome hovers over another Newsom initiative, improvement of care for the mentally ill, and, of course, the homelessness crisis has actually worsened during his governorship.

Related Articles

Mathews: Capitol Annex Project breaks California lawmakers’ own rules

California to invest $500 million in zero-emission school buses

Skelton: Newsom and lawmakers bow to Google, killing help for news industry

Bill to limit phone use in schools awaits governor’s signature

BART charges ahead with building more electric vehicle plugs following federal grant

Newsom’s greatest mistake, and one that will haunt the state indefinitely, was his 2022 declaration of a $97.5 billion budget surplus. “No other state in American history has ever experienced a surplus as large as this,” Newsom bragged, igniting a frenzy of spending.

The surplus was a mirage. Newsom and his budget team assumed that a one-time spike in revenues would continue indefinitely, creating what was later acknowledged to be a $165 billion error over four years.

The phantom surplus morphed into a multibillion-dollar deficit, forcing Newsom to slash spending, dip into emergency reserves and borrow money to paper over the gap. The underlying divide between income and outgo will still be there in 2027 — when Newsom hands the keys to his successor.

Dan Walters is a CalMatters columnist.