Lauren Rosenthal, Brian K. Sullivan and Christopher Cannon, Bloomberg News

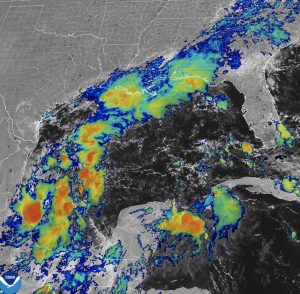

Forecasters had warned for days that Hurricane Helene was likely to cause widespread devastation. But when the powerful storm struck Florida and barreled through the eastern U.S. last week, killing more than 180 people and taking whole communities offline, it still managed to come as a shock.

Florida’s Big Bend, where Helene made landfall, previously went decades without a hurricane strike. In the past year or so, it has now seen three. The western half of North Carolina, once held up as a haven from the worst impacts of climate change, has been paralyzed by floods.

Across the U.S., natural catastrophes are becoming more expensive and more common. Global warming is supercharging the atmosphere with more water and energy, fueling increasingly violent weather. The destructive storms, droughts, floods and wildfires are colliding with communities where millions of people live, with more costly homes and possessions — and so much more to lose.

A motorist passes flood damage at a bridge across Mill Creek in the aftermath of Hurricane Helene on September 30, 2024 in Old Fort, North Carolina. (Photo by Sean Rayford/Getty Images)

“Pretty much 50% of the population lives within miles of the sea, more exposed to hurricanes and with an aging infrastructure that is not set for today’s climate,” said Mari Tye, a scientist and civil engineer at the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colorado.

Take North Carolina. The state only experienced one or two billion-dollar disasters — including storms, fires and floods — a year on average from 1980 to 2009. Now, the new normal is closer to six or seven, according to inflation-adjusted data from the U.S. National Centers for Environmental Information, which catalogs economic losses from severe weather.

At the same time, North Carolina’s population has been growing. It’s added nearly 400,000 new residents since April 2020, early in the Covid-19 pandemic. Those affected by Helene could now face weeks without water and power. They’re also physically isolated, as bridges have collapsed throughout the region, leaving people stranded.

“The restoration has been very very complex due to the extreme nature of the damage in many areas,” Ken Buell, a deputy director with the U.S. Energy Department, said in a press briefing Thursday. “In some areas we are looking at an expedited rebuild of the energy system or a rebuild of the entire community before power can be restored.”

Many roads, dams and electrical grids in the U.S. were designed and built for a world that no longer exists, Tye said, and new construction is struggling to keep up with increasingly frequent and disruptive storms. “You are designing for what was once a rare event,” Tye said.

The price tag of a weather disaster can be hard to assess immediately. It includes the physical damage to infrastructure, homes, businesses and lost crops and livestock, as well as the hit to economic activity as a region struggles to get back on its feet.

Across the U.S., these losses have been rising sharply for the past several decades, even accounting for inflation, as disasters tear through increasingly valuable real estate and other assets. The nation’s median home price has more than doubled since 2000 and car prices have also risen, said Chuck Watson, a disaster modeler with Enki Research. Add population growth to that equation and “it’s so easy to hit $1 billion in impacts these days,’’ he said.

Hurricane Helene is poised to be one of the costliest storms on record in the U.S., with damages of up to $250 billion across at least a half-dozen states, according to commercial forecaster AccuWeather. Watson at Enki Research estimates that more direct economic losses will be somewhere between $30 billion to $35 billion. Republican House Speaker Mike Johnson said Wednesday that the cash-strapped Federal Emergency Management Agency doesn’t have enough funds to help all of Helene’s victims.

“Congress will have to address it,” Johnson told Fox News. “I mean, this is an appropriate role for the federal government.”

One of the largest U.S. states is its most vulnerable. Texas has long been the US epicenter of extreme weather. Since 1980, it’s logged 186 weather disasters costing $1 billion or more, according to the NCEI. That’s 57 more than Georgia, the next-closest state. Texas has also racked up the most costs tied to extreme weather of any state, with damages totaling at least $300 billion since 1980.

This year alone, Texas has already seen back-to-back disasters. Starting in February, the state’s largest-ever wildfire burned more than 1 million acres across the Panhandle. In May, a derecho punched windows out of Houston skyscrapers and storms dropped giant hailstones. Weeks later, Tropical Storm Alberto shut down Corpus Christi’s port and flooded coastal towns. And in July, Hurricane Beryl arrived, knocking out power to more than 2.5 million homes and businesses around Houston for more than a week.

A property is seen in flames as the Park fire continues to burn near Paynes Creek in unincorporated Tehama County, California, on July 26, 2024. (Josh Edelson/AFP/Getty Images/TNS)

A planet that’s getting hotter, driven by rising carbon emissions, is one factor causing more destructive weather. On average, the atmosphere holds 7% more moisture with each degree of warming, said Deborah Brosnan, a marine and climate scientist based in Washington, D.C. Ocean heat has also reached new records in the last year, accelerating evaporation rates and feeding more intense and frequent rainfall.

“Major hurricanes are now more likely because of the extra fuel they can extract from warmer oceans,” said Jennifer Francis, a senior scientist at the Woodwell Climate Research Center in Massachusetts. “Their storm surges ride on higher sea levels, inflicting devastation farther inland.”

Research suggests that higher global temperatures mean hurricanes will be able to survive longer over land before dissipating. That increases the chance that communities further inland — which aren’t accustomed to tropical weather and might not heed hurricane advisories — will experience severe wind damage and more rainfall.

A planet that’s heating up also means that dry areas can become even drier, adding to fire and drought risks. California saw its fourth largest wildfire with July’s Park fire, which scorched more than 425,000 acres across the Central Valley region.

And, of course, the Earth will simply feel hotter as temperatures increase. “The most direct link between climate change and extreme weather is worsening heat waves,’’ Francis said. “As the globe warms generally, heat waves are becoming more intense, widespread and longer lasting.’’

Related Articles

Bay Area’s early October heat wave to persist through the weekend

Two Central California farmworkers test positive for bird flu

PRO/CON: Is California’s Prop. 4 climate bond a smart move or just too expensive?

Trump OK’d California wildfire aid in 2018 only after reviewing voter data, former official says

7 horses euthanized at California race course due to infectious disease

That puts pressure on agriculture, utilities, ecosystems and people, which are all struggling to adapt to new extremes, Francis said. This has become evident as drought has spread and electric grids have buckled from increased demand as people turn to air conditioning to cool down.

Daniel Swain, a climatologist at the University of California Los Angeles, said Hurricane Helene is a powerful reminder that “the ceiling on how bad things can get essentially has risen.”

In Asheville, North Carolina, Helene smashed flood records set in 1916 and left at least 57 people dead in the surrounding county. While first responders and government agencies focus on helping Helene’s victims, Swain said it’s important to start having conversations about whether other communities are prepared to face their own versions of Helene — weather events that are unusually violent, but not without precedent.

“We have to be honest about why things unfolded as they did,” Swain said. “Part of that conversation is about the role of climate change, which is not insignificant in cases like this.”

With assistance from Rachael Dottle, Marie Monteleone and Ari Natter.

©2024 Bloomberg L.P. Visit bloomberg.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.