ALBANY — No one disagrees that the city of Albany blundered in its decision to accept parkland in the 1970s that prominently displayed a 28-foot Christian cross atop Albany Hill.

But conflict ultimately erupted over deep disagreements about how to resolve constitutional concerns about the separation of church and state while honoring residents’ First Amendment rights — devolving into an intense, nine-year legal spat over the fate of the electrically illuminated steel-and-plexiglass cross.

That saga is officially over.

During the Albany City Council’s Oct. 7 meeting, City Attorney Mala Subramanian announced that the city stipulated a judgment that settles all legal claims and forces Albany to pay the Albany Lions Club $1.53 million for the acquisition of the community service group’s property interest, $500,000 of which has already been set aside in escrow with the State Condemnation Fund.

In 1971, Hubert “Red” Call, a Lions Club member and councilmember who owned the 1.1-acre property, had the cross installed on his land — setting up an easement before selling his land to a developer, who later gave the property to the city in 1973 to use as a public park.

Subramanian explained that when the city acquired Albany Hill Park, the plot of land was encumbered with that easement, allowing the cross’ preservation.

Related Articles

East Bay man arrested on suspicion of killing mother, half-brother

Berkeley police officer injured in stolen car pursuit

Alameda County DA Pamela Price vows changes as hundreds of misdemeanor cases languish past statute of limitations

Oakland Mayor Sheng Thao adamant as recall looms: ‘Crime is down’

2 men got 15 years for killing man during Oakland marijuana robbery, but the guy who set it up received leniency and accolades

Public scrutiny of the cross escalated in 2015 when groups such as the East Bay Atheists and the Freedom From Religion Foundation sent letters to the city demanding its removal.

By June 2018, a federal judge ruled the cross violates the establishment clause of the First Amendment because governments are forbidden from promoting one religion over another. The 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals upheld that decision in December 2019.

That’s largely why the city decided to condemn the easement in April 2022 and quietly remove the cross last June, which Subramanian said “did not infringe on anyone’s rights.”

“The city successfully defended numerous challenges and claims brought by the Lions Club to try and block the removal of the cross,” Subramanian said last week. The city’s full statement is posted on its website, alongside other background information on the history of the Albany Hill Cross. “This (judgment) resolves the matter, and therefore, the Lions Club has no legal right to use the property for the easement or to maintain the cross on the property, which the City has already removed.”

ALBANY, CA – APRIL 25: Saul Geiser, of Albany, left, walks with Jasmine Buczek, of Oakland, as they walk past the cross at Albany Hill Park in Albany, Calif., on Monday, April 25, 2822. The Albany city council voted in favor of removing the cross. The cross was erected by the Albany Lions Club in 1971. (Jose Carlos Fajardo/Bay Area News Group)

Last week’s settlement was a victory for opponents who have long decried the cross’ existence as a city-owned landmark.

Councilmember Aaron Tiedemann said he’s largely heard positive reactions to the cross’ removal. While there’s a small but loud contingent that continues to defend the cross, he said he typically receives those comments from Lions Club members, relatives of the original property owners’ family, or people living outside of the Bay Area.

“Most people I’ve talked to are happy to see that it’s gone,” Tiedemann said Tuesday, explaining that removing the symbol is more aligned with the current community’s values. “People have viewed it as a sign of intolerance, and it’s better to have it gone. It’s a shame it took such a long, convoluted process, but that’s basically where we ended up due to decisions that happened 50 years ago that wouldn’t have been legal now.”

Tiedemann said the final $1.53 million payout is an amount the city can plan around without having to cut any programs or services.

“I’m not thrilled at the amount of money and time we had to put into it, but I think we knew that was a risk at the start, and it was something that we thought was worth it anyway,” Tiedemann said. “How I understand it, this is the end.”

Robert Nichols, a Lions Club member who served as the group’s attorney, said the club will start considering its options to relocate the cross — maintaining its purpose to provide community members a place to pray in solitude.

But that doesn’t mean the Lions Club is pleased with the final outcome.

“I think that the club is disappointed (by the settlement), but it was becoming rather clear that the city was not going to yield and that the courts were not going to provide any protection for this religious symbol,” Nichols said Tuesday. “As a consequence, I think that the Lions Club has adopted an alternative which is the next best solution: receiving funds which should allow them to reconstruct the cross at another location that’s not public property, and continue the practices that it has had for the last 50 years.”

While Nichols acknowledges that the troubled history of the cross’ installation may have necessitated the legal battle, he said the lengthy process to resolve the issue could have been different.

“I think there are a lot of arguments to be made that the city wasn’t completely in the right in this situation, either,” Nichols said, referring to the original 1970s land agreements. “Suddenly 50 years later, (the city) changed their mind, so there were a lot of issues there that, in fairness, don’t seem correct and probably had a serious effect on this unique situation.”

This final judgment over the cross is a disappointing blow for people such as Dorena Osborn, Hubert “Red” Call’s granddaughter, who advocated for the cross to stay on the land her family expressly dedicated for that purpose five decades ago.

Osborn holds firm that the city could have saved itself time and money by accepting the Lions Club’s offers to purchase the land surrounding the cross, which she said could have addressed looming legal concerns and allowed the structure to remain on Albany Hill.

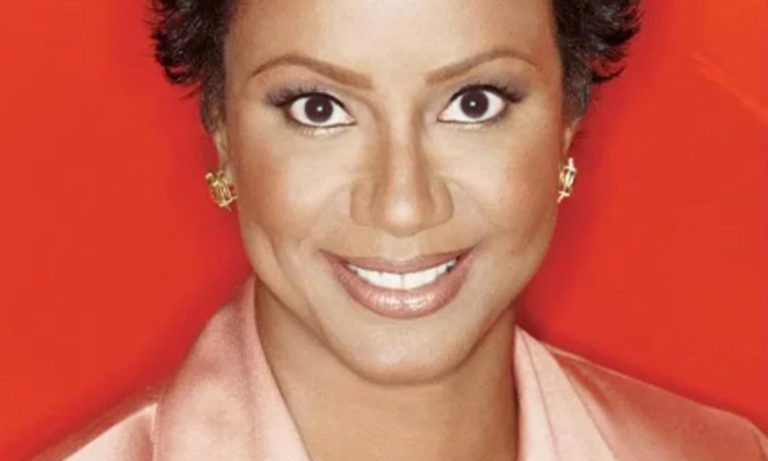

However, she said the city “wanted nothing less than to take it down,” calling out elected officials such as former Councilmember Rochelle Nason, who has openly denounced options to keep the cross because that doesn’t solve the city’s problem or its mission to “achieve a park that’s appropriate for everybody to enjoy.”

Now, Osborn said the cross’ removal is persecution that will punish generations of Christians and Bay Area residents to come.

“The injustice happened when the city took the cross off the land that my grandparents set aside for the rest of time,” Osborn said Wednesday, adding that claims that the cross is reminiscent of KKK cross-burnings in the East Bay hills decades ago have been twisted to advocate for its removal. “The sin of this injustice goes so far deep that it definitely stretches my ability to forgive … but God can and does forgive, and we’re called to do the same.

“I’m still praying for a miracle — some divine intervention.”

Emily Berriault, left, Dorena Osborn and Kevin Pople visit the site of the former Albany Cross, Friday, June 23, 2023, two weeks after the 28-foot tall structure was removed from its foundation by the city of Albany. They are fighting to have the cross resurrected. (Karl Mondon/Bay Area News Group)