So far in 2024, severe injuries caused by falls from the U.S.-Mexico border wall are up 58 percent compared to 2023, and that number will increase, as the annual total for this year is not yet complete.

These numbers come from Scripps Mercy Hospital and UC San Diego Medical Center. Together, the two Hillcrest hospitals provide trauma services for a 30-mile stretch of the border from the Pacific Ocean to Tecate.

In 2023, these two facilities collectively recorded 629 falls from the 30-foot steel structure severe enough to result in a hospital stay. So far in 2024, the total number of severe falls is up to 993, though that number is incomplete. UC San Diego data covers January through September while the total provided by Scripps runs through August.

Each facility, then, has averaged two border fall admissions per day, about double the caseload observed in 2021, when the number of falls spiked significantly.

Why is this increase occurring? The U.S. Border Patrol did not provide an answer when asked, and the two health systems directly receiving the bulk of trauma cases also were reluctant to cite any specific cause.

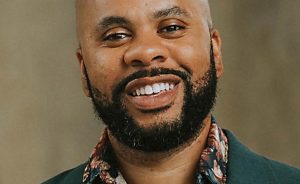

However, Pedro Rios, who directs the U.S.-Mexico Border Program run by American Friends Service Committee, a nonprofit that aids those who are regularly trapped between San Diego’s two parallel border walls, provided a working hypothesis.

This year, Rios noted, Mexican authorities have set up checkpoints farther east, out toward the rural community of Jacumba, where there is a single wall more easily breached and crossings had become more common.

“That forced the migration routes to move both east and west,” Rios said. “My conclusion would be that this shift means that people are crossing in areas where there are more layers of border wall, which increases the possibility of injuries and deaths.”

While the increased demand for expensive trauma services, especially the orthopedic surgeries often required by those who fracture lower limbs, pelvic bones and heel bones, consumes resources, neither facility’s leadership said that the increased flow has overwhelmed treatment capacity.

But that does not mean those on the edge of this trend are unconcerned with the increase that has been observed, especially given that trauma-level falls used to be relatively rare. These two facilities recorded just 80 in 2019, the year that the federal government increased the wall’s height at the specific direction of then-President Donald Trump.

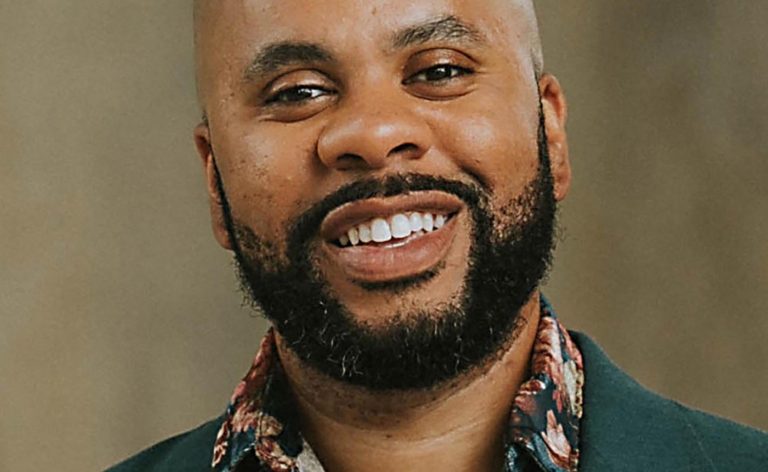

“The fear always has been not the two or three or five that come to us daily, but what would happen if it was 50 or 100 in a day,” said Dr. Vishal Bansal, director of trauma surgery at Scripps Mercy.

While such large numbers might seem like a fantasy to the average person, the physician notes one can’t help think about a possible worst-case scenario.

Imagine, he said, a large number of people climbing a relatively small section of the wall simultaneously and causing a collapse.

“If something like that happened, it could cause mass casualties, and that would effectively shut down the trauma system for several days,” Bansal said.

On a recent morning, the trauma team at Scripps Mercy gathered for morning rounds, working their way through 30 cases occupying hospital beds. Four of them were related to border falls, with lower extremity injuries that generally required a few days to heal enough for discharge. This, physicians and nurses said, was a slower period. At times, up to a third of the patients in Mercy trauma beds have been those who have suffered border wall falls.

Most are discharged to family members, usually in other parts of the country, officials said. Patients generally must work to get enough cash from often-distant relations in the U.S. to purchase a plane ticket elsewhere. The alternative is to return to the border and turn oneself in to the U.S. Border Patrol, making a claim for asylum in the United States.

This, one nurse said, almost never happens. The vast majority leave and make such a claim elsewhere.

Rios, the border outreach director with American Friends Service Committee, which maintains round-the-clock observation of the no-man’s land between the two border walls west of the San Ysidro Port of Entry, confirmed that, once treated, migrants are generally released by health care providers. Border Patrol agents generally do not stay with them at hospitals during treatment.

Once released, migrants are able to file an “affirmative” asylum claim, the process for those “physically present in the United States,” according to the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Service.

It’s much different than filing an asylum claim while still in Mexico, where migrants face a wide range of difficulties and expenses waiting for asylum decisions which, according to many accounts, are often rejected. A 2023 account from The New York Times found, for example, that “the number of single-adult migrants who are able to pass initial screenings at the border has dropped from 83% to 43%” under a new asylum policy that took effect in 2023.

Some might wonder if those falling from the border wall are doing so out of a desire to file an asylum claim from inside the United States, given that so many who do so from south of the border do not succeed.

Rios said he has found no such sentiment among the many migrants he has spoken with. Most, he said, seem to simply want to reach the United States and have been caught up in a process that is out of their control.

He noted that border crossing is controlled by Mexican cartels that charge thousands of dollars for each crossing. But, when a migrant purchases such services, he said, the exact methods that will be used are not specified.

Related Articles

A kitchen staffed by trans women is a refuge for Mexico City’s LGBTQ+ community

Fraud trial begins for California businesswoman who got clemency from Donald Trump

At the epicenter of the Mexican drug trade, a deadly power struggle shuts down a city

Claudia Sheinbaum to be sworn in as 1st female president of Mexico, a country with pressing problems

Mexico travel risk map: U.S. issues new warnings

“They are taken to a safe house and they might be there for half a day before they’re taken to the border wall, and they’re confronted with a ladder and told, ‘this is how you’re getting over,’” Rios said. “At that point, there really is little opportunity to turn back, because they’re dealing with people that might be involved with organized crime or smuggling networks that can’t necessarily be trusted.

“They sort of feel compelled to cross that way.”

Given that the border walls are constructed of steel slats that can be seen through, some might wonder why authorities don’t just knock the ladders down shortly after they’re put up. Rios said that many ladders are knocked down in this way, but smugglers are clever. They often wait until it is dark outside or for fog to roll through the Tijuana River Valley before making an attempt. Sometimes, surges have been known to occur on holidays when it is suspected that government agencies will have fewer officers on duty.

And, Rios added, the speed at which the whole process occurs makes it difficult for Mexican National Guard members to pull them down before human injury becomes a likelihood.

“It’s such a fast process that people might already be climbing the ladder and tipping it over could cause even greater injury,” he said, recalling one case where a ladder was knocked down after a woman’s daughter had made it over but she had not, injuring a mother and separating her from her child.

It takes a severe injury to end up in a hospital’s trauma unit. Those who fall from the wall and sustain sprained ankles or minor cuts, for example, are treated at the border and not transported. But there is a gradation of injury even among those hurt badly enough to be sent to a trauma unit. The most severely injured end up in hospital intensive care units, which offer advanced life support, such as the use of mechanical breathing machines called ventilators.

Though comprehensive data on how many border wall trauma patients have been severely injured enough to require intensive care admission was not available, UC San Diego Health provided a breakdown of its patients, indicating that 8 percent of all border wall falls have been admitted to its ICU since 2019. This year, however, while trauma unit admissions are up significantly, only 4 percent have been so grievously injured that they end up in the ICU. That trend is reflected in the amount of time that border fall patients have spent in the hospital. The median length of stay this year has been two days compared to three in 2023, when 7 percent of border falls landed in the ICU.

These most-severe cases, Bansal said, can be extremely difficult to treat successfully. One recent example, he said, was a patient who suffered a severe traumatic brain injury after falling from the wall and though surgeons tried to relieve the pressure of swelling by removing part of the patient’s skull, they died.

Such medical intervention does not come without cost.

UCSD does receive some reimbursement for patient care, though it falls short of covering costs incurred. Total gross charges for patients seen in 2023 and 2024 were $151 million, with about $24 million of that total not reimbursed.