Nathan Beukema has been playing “Dungeons & Dragons” — DnD for short — for 37 years, and says role-playing games like this have helped him through life’s challenges.

This is a storytelling game, in which players assume the roles of imaginary characters and form parties that explore fantasy worlds and embark on epic quests. Games — which can last for hours — are run by a player designated as the Dungeon Master (DM), who acts as a kind of referee and lead storyteller.

“Role-playing games help me get through life — without them, it would be intolerable,” says Beukema, 49, of Los Angeles. “But with these games and these friends, I can express myself and make it a shared experience, which is what is cathartic about it.”

His character concepts “tend to veer towards those that don’t take crap from other people. Someone that will jump up with a sword the instant you threaten them.”

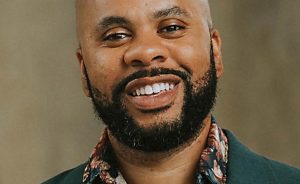

Beukema, who is part of the Los Angeles-based tabletop role-playing game (TTRPG) group RolePlay GrabBag, is also part of the diverse, large, loyal community and fandom of the iconic “Dungeons & Dragons,” which turns 50 in 2024.

Mo Williams, of Los Angeles — who, along with Shaun Leonard, of Los Angeles, and Kevin Roy, of Sherman Oaks, also is a member of RolePlay GrabBag, which posts videos on YouTube — believes the game is bigger than ever, has a broad appeal and is great for beginners.

“Your job is to have fun and it’s the [Dungeon Master’s] job to help you navigate the rules, plus it’s collaborative so the other players will help you as well,” he explains. “People who play DnD generally want new people to play DnD, so ‘knowing how to play’ isn’t a prerequisite; most of the time it’s an advantage because you come up with ideas veteran players have never considered. Adults will enjoy it because all you have to do is sit down at the table, describe what you want to do and roll some dice.”

Williams says 2014’s highly successful fifth edition of the game — along with shows like “Stranger Things,” “Critical Role” and “Dimension 20,” not to mention celebrity players like Stephen Colbert, Deborah Ann Woll and Joe Manganiello — have helped popularize “Dungeons & Dragons” beyond niche audiences.

“There are 64 million DnD fans worldwide. Some play the game regularly. Others enjoy the game by watching movies or television shows, or playing DnD-inspired video games. Increasingly, many fans enjoy watching celebrities play the game on YouTube and Twitch,” says Jason Tondro, senior designer at Wizards of the Coast, which owns “Dungeons & Dragons.”

“DnD brings people together. It’s about strangers sitting down around a table and working together, becoming friends along the way. We have a motto in DnD: Never split the party. That cooperative element is only part of what makes DnD special. DnD has influenced worldwide culture in ways many people don’t even know. Leveling up, for example, comes from DnD. That’s just one example.”

The game

Devotees of “Dungeons & Dragons” say the collaborative storytelling and role-playing exercises make this game-playing experience special.

“You create a character, explore fantastical worlds, fight monsters and role-play social interactions,” Williams says. “One of the great things about DnD is that the rules are highly flexible. Most players who start playing DnD, and even many who have been playing for years, don’t know all the rules. I say this because one of the things that I think intimidates potential new players is that they think they need to learn a bunch of rules; you don’t. You just need to like the idea of choose-your-own adventure stories, really. You don’t even need to come up with your own character if you don’t want to, as there are plenty of pre-made ones available.”

Williams says the goal of the game is to live out a story.

“There is no ‘winning’ in DnD in the traditional sense of a board game,” he says. “You win by working together to slay the monster, rescue the prince or stop an evil lich from being resurrected, as a few examples. An adventure can be any story that your group finds fun and interesting. Some adventures are silly, some are scary, it all depends on how your group likes to play. Some players use accents or voices, some just plainly narrate what they want their character to do. It varies widely.”

He says the core game works like this: You play a character with a set of “stats” — like in a video game. Depending on your character, you’ll be better at some things and worse at others. For example, you could be a Dwarf Barbarian that is strong and fast, but not very intelligent.

The Dungeon Master (DM) presents you with a situation and you decide what your character wants to do in that situation. You look at your stats and roll dice to see if you are successful or not. A new situation is created and the story moves forward.

Tondro says there are many things that make “Dungeons & Dragons” unique.

“There’s no board — players describe what their characters do, they roll some dice and the DM tells them what happened,” he says. “Players aren’t competing against each other; they’re working together to solve problems and celebrate their successes.”

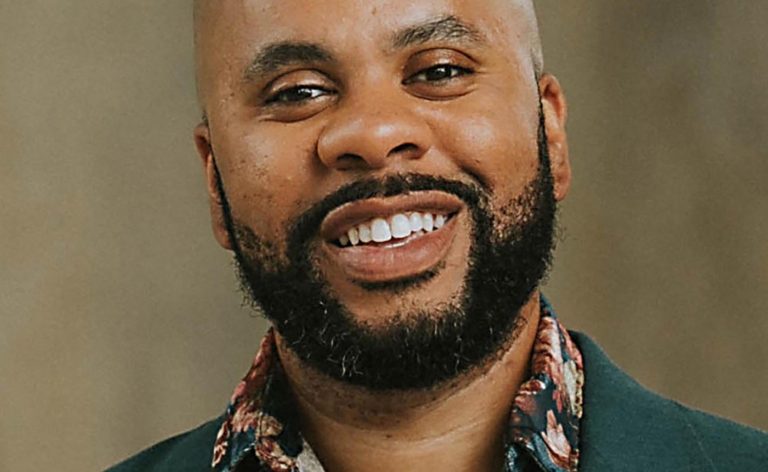

Dungeon Master, Mo Williams leads a three player game of Dungeons and Dragons in Sherman Oaks on Sunday, Aug. 11, 2024. (Photo by Drew A. Kelley, Contributing Photographer)

DnD lore

As Tondro tells it, in 1973 Dave Arneson, then a University of Minnesota student, drove up to Lake Geneva, Wisconsin, to demonstrate his “Blackmoor” game for game designer Gary Gygax and friends. Gygax was so intrigued by what he saw that he worked with Arneson to develop his concept. By 1974, “Dungeons & Dragons” was created. (The long history is detailed in the book, “The Making of Original Dungeons & Dragons,” released this year.)

Then, something terrible happened.

“In 1979, a college kid named James Egbert went missing,” Tondro says. “His parents hired a private investigator who concluded, rapidly and with no evidence, that DnD was somehow responsible for James’ disappearance. The negative publicity from this nevertheless made DnD a household word, and sales of the game exploded.”

Tondro explains that “Dungeons & Dragons” began as a $10 box of three booklets that were more like guidelines than actual rules. Gygax and Arneson encouraged readers to make their own game, using the contents of this box as a starting point.

“And that’s what happened,” he says. “In California, the key group was led by Lee Gold, whose fanzine Alarums and Excursions is still in publication today. The importance of Gold and A&E to the spread of early DnD can’t be understated.”

Around 1979, Gygax and others decided the game needed to be entirely redesigned — which led to “Advanced Dungeons & Dragons.” The game has gone through several more editions since then. Wizards of the Coast bought the “Dungeons & Dragons” original publisher, Tactical Studies Rules (TSR), in 1997 and developed the third edition of the game. The current edition, the fifth, premiered in 2014 and has recently been revised.

Tondro says “Dungeons & Dragons” was the first of the role-playing games and is often the way new people discover the hobby.

“There are many, many other role-playing games out there in the world,” he says. “But most gamers, by far, the first RPG they play is DnD. We’re the first impression, and that’s a responsibility we take very seriously.”

From right, Nathan Beukema, John Constance and Kevin Roy play a game of Dungeons and Dragons in Sherman Oaks on Sunday, Aug. 11, 2024. (Photo by Drew A. Kelley, Contributing Photographer)

The community

Beukema has been playing the game since he was 12.

“When I was a child, I often stayed with my aunt because my parents’ marriage was a disaster,” he says. “They were both addicts and their fighting would often escalate to violence. I did not deal with it well, so I would stay with my mom’s sister on weekends. During the summer, I would play with her stepson, Greg, who was three years older than me.”

He says he didn’t do well in school, but the game helped him.

“With my home life, I couldn’t focus on schoolwork and my grades were terrible,” he says. “But DnD made me interested in reading. I devoured books on history, mythology and fantasy because they were related to my hobby. I developed improvisation skills purely out of necessity. As a Dungeon Master, you have to think [on] your feet creatively and react to the player’s actions without losing pacing. Math is also essential in ‘Dungeons & Dragons’ — adding up bonuses and penalties and assigning difficulties to tasks can be challenging, especially since you must do it while entertaining everyone and ensuring the game keeps momentum.”

But unlike school, this wasn’t boring for him, he says. It wasn’t about the memorization of facts or formulas. It was a practical application doing something he loved.

“I had decent grades by graduation, even though I still hated school,” he says. “I attribute that to DnD stimulating my curiosity and giving me a reason to learn. I even have excellent handwriting because of all those years of writing character sheets by hand.”

Roy, who is a freelance director/writer/producer in the film/TV industry, says he’s been playing the game and RPGs since he was in high school, around 1992.

“The community is huge,” Roy says. “It means a lot for players, especially those who were never represented before. Access to the game is bigger [now], so you have more people playing it and commenting on it and creating diverse characters and stories and worlds. I’m not sure if this was the point of DnD at the start, but growing up playing I learned a lot about race and hate and acceptance. Playing a species like a Dwarf or Gnome or an Elf that wasn’t accepted in a Human town put me into the perspective of people in the real world who deal with similar issues. This was all innocent fantasy where nobody really got hurt, but through story and situation it taught me a lot about the real world and real-world issues. It made me a less judgmental person, a more accepting person, and it taught me so much about perspective.”

Originally from Galway, Ireland, Leonard says he’s been playing the game for 20 years.

“My older brothers all played it together, and I remember trying to eavesdrop on their game when I was little,” he says. “Once I was old enough, my eldest brother, Mark, invited me into a campaign in the third edition, and I was hooked. Later, my friends and I watched the ‘Community’ episode about DnD, and they asked me to run a game for them. Since then, I’ve been running a TTRPG of some kind for my friends, or professionally at conventions or as part of an after-school program.”

He says that the community is broad and seems to be getting broader and more inclusive over time.

“The DnD community ranges from number-crunching power-gamers to drama-loving improvers, from old-school ‘Kill me DM’ players to a new generation of emotionally invested storytellers,” he says. “When you meet someone else who plays DnD, you immediately have a conversation starter and a frame of reference. You ask: ‘What class do you play the most?’ or ‘Are you a forever DM or do they let you play sometimes?’ Talking about a hobby is always a uniting activity, but in this case you’re also asking, ‘What was your most recent adventure?’ I think in any other context it would seem strange to ask someone about their mythic fantasies, but in DnD, we all want to know each other’s dreams and make-believes.”