I recently had some time to pass, so I meandered around a local park for half an hour: just a normal park, mixing stands of diverse ornamental trees with areas of lawns. But even here on a cool and quiet, misty and slightly drizzly day on the border of fall and winter, there were birds to be found. Far more birds than people, who mostly seemed to assume that such damp days were no time for outdoor recreation. But why stay home? Even on the days of sunless mist, there are living things out there that are ready to brighten your day.

The initial few moments were quiet — deceptively so. In winter, many birds congregate in flocks, so you can pass quickly from a silent moment when you are where the flock is not to the midst of a bubbling crowd. At first, even I thought there were no birds, but then I approached a treetop full of lesser goldfinches, which occasionally emitted their characteristic sinking whistles, their melancholy high “tee-yee” sounding more forlorn than usual against the gray sky. “Lesser,” of course, is a misnomer, recognizing only their relative diminutiveness of size while failing to appreciate their extraordinary capacities of song or status as a regional specialty — I prefer to call them by their old folk name, “green-backed goldfinch.”

Leaving the flock of greenbacks, I continued my slow meander, and with the mere virtue of passing time, birds inevitably revealed themselves. A white-breasted nuthatch honked invisibly from an oak, earning them their folk name, “big quank.” A flicker trumpeted in the distance and I searched for the bird, finding it at last silhouetted against the sky near the top of a planted redwood, pumping its head characteristically as it turned back and forth. A solitary black phoebe perched on a bench back, pausing from its fly-catching flights and puffing up against the chill.

I ran into another busy flock, this time encountering a mostly grounded group of white-crowned sparrows. Many were young birds, striped, despite their name, in brown and tan upon their heads. They were only born last spring, somewhere in the Northwest, but were already veterans of a 1,000-mile journey before their half-year birthday. Further flocks punctuated the low simmer of solitary birds, periodically enlivening the quiet day with similar bursts of activity. A dozen house finches dotted a treetop in scarlet highlights — “linnets like wounds,” as poet Robert Hass once wrote — while two dozen yellow-rumped warblers were the liveliest yet, moving through the canopy with vigor, dashing out in quick sallying flights to catch insects in mid-air or hovering before a leaf to grab some otherwise inaccessible prey.

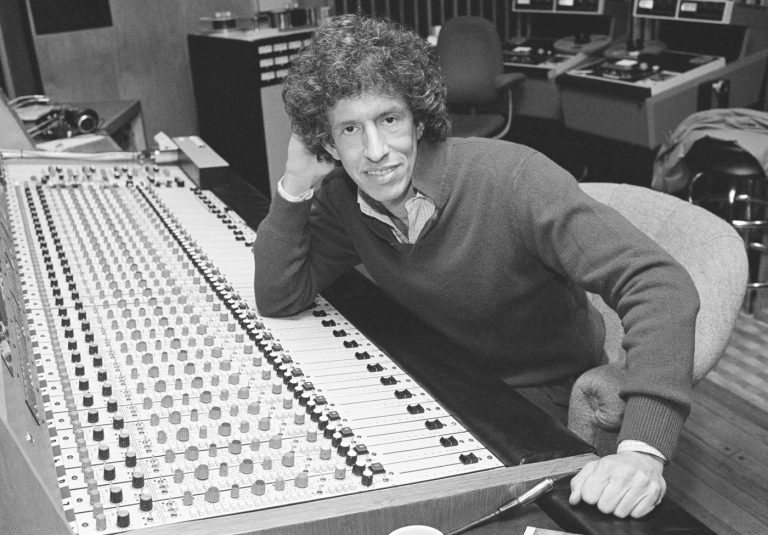

Great blue herons can hunt gophers on lawns, as well as reptiles and insects. (Photo by Allan Hack)

Related Articles

Should Bay Area birdwatchers take down their feeders to avoid avian flu?

Views on garden insects are changing. Why many former ‘pests’ are now valued

How DNA could help save California’s historic pheasants

Why can’t Oakland hummingbird decide whether to sit or hover at the feeder?

Alameda County detects bird flu in child with mild symptoms

A town park is mostly populated by common birds, but it’s often precisely the most common birds that we neglect and take for granted. Consider an Anna’s hummingbird. This is our year-round, ever-present hummingbird, attractable in essentially any yard with a simple offering of sugar water. I ran into one that was busily visiting the ornamental flowers. This is a bird that has expanded its range in sync with human populations: we two flower lovers making common cause as we bring blossoms to the winter — for their enthusiastic enjoyment. And yet most of the continent doesn’t have hummingbirds in winter, and most of the world doesn’t have hummingbirds at all. When European explorers first reported these creatures to their compatriots in the old country, they were held to be wondrous and amazing creatures, a fit subject for sooty Londoners to gawk at in museums. They are equally wondrous today, hovering effortlessly before my eyes among the unused playground equipment.

I could keep going. The most mundane and underappreciated birds have plenty to be said in their defense: I saw starlings, crows and pigeons, often disdained for their success. A few striking individuals stood tall among these crowds of little birds — a red-shouldered hawk glowered from a tree, perching closer to the ground than usual in the relative absence of humans on this drizzly day, while a great blue heron similarly took advantage of the vacant lawn to stride among the gopher mounds. All of this was there, without distant exploration or optimally comfortable conditions. All of these birds were there, as they always are.

Jack Gedney’s On the Wing runs every other Monday. He is a co-owner of Wild Birds Unlimited in Novato and author of “The Birds in the Oaks: Secret Voices of the Western Woods.” You can reach him at jack@natureinnovato.com.