Even amongst cult performers, Robbie Basho stands out as an artist whose influence far outstripped his modest output.

Based in Berkeley for much of his career, the self-taught guitarist, composer and vocalist helped create a raga-meets-folk sound in the 1960s that became a foundational element of the American primitive guitar movement. Until recently, his oeuvre consisted of 14 albums containing 10 hours of music recorded over less than two decades.

Courting obscurity in the years before his death in 1986 at the age of 45 from a freak chiropractic accident in the East Bay town of Albany, Basho was hailed as a source of inspiration by fellow guitarists such as Alex de Grassi, Leo Kottke, and even The Who’s Pete Townshend. William Ackerman said that Basho’s music led him to launch the Windham Hill label, which released one of his final records, 1979’s “Art of the Acoustic Steel String Guitar 6 & 12.”

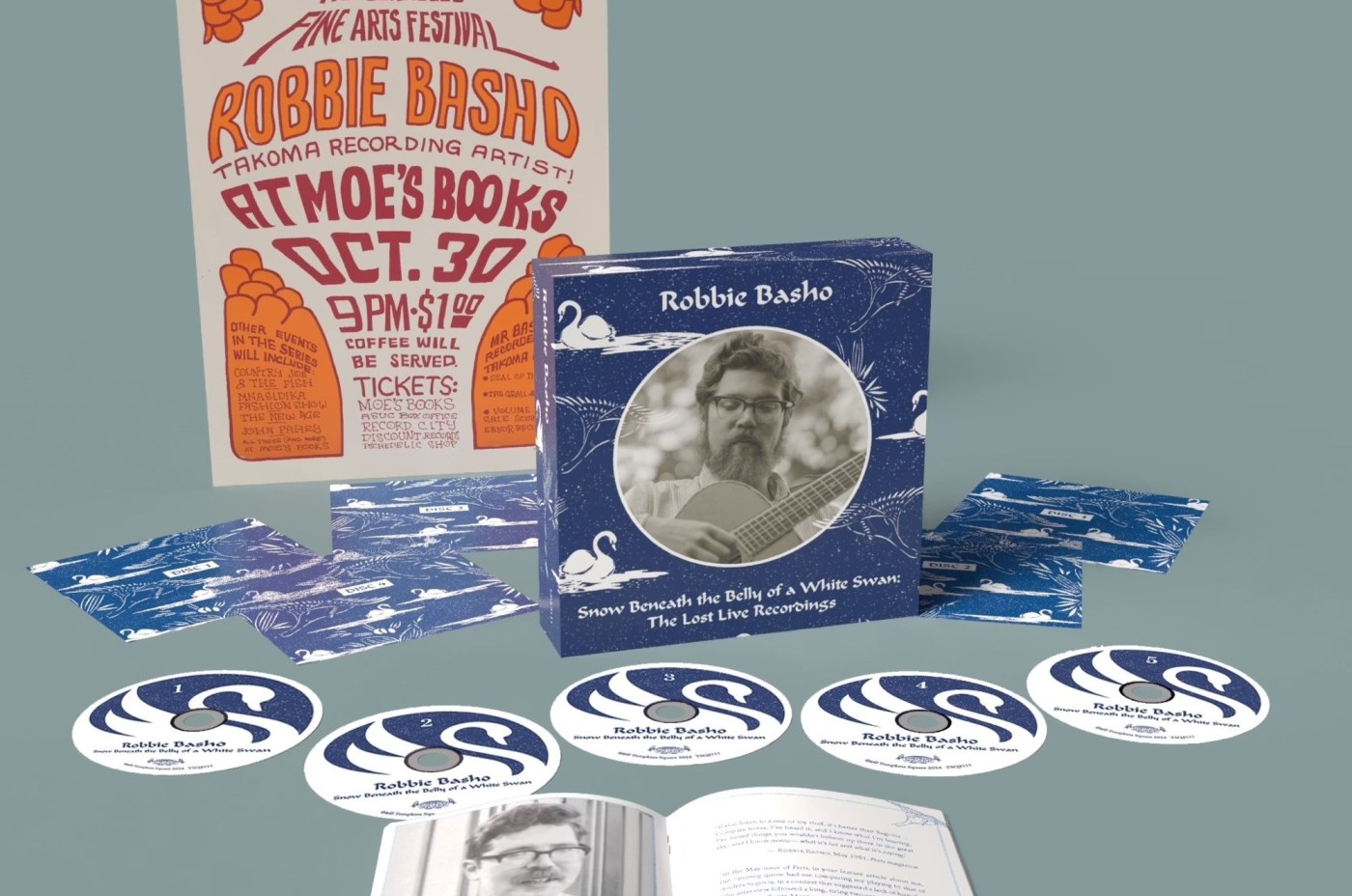

Rediscovered by a wave of new fans in recent years, Basho gained a burst of attention when San Francisco-based Tompkins Square records released the 2020 box set “Song of the Avatars: The Lost Master Tapes,” a compendium of previously unheard studio recordings discovered by British filmmaker Liam Barker while he was researching his 2015 documentary “Voice of the Eagle: The Enigma of Robbie Basho.”

A limited release, “Song of the Avatars” sold-out within days, and now Tompkins Square is back with a revelatory new project that goes a considerable way toward unwrapping the Basho enigma. Gleaned from a trove of reel-to-reel tapes that Barker recovered from the Walnut Creek-based spiritual community Sufi Reoriented, where Basho became a disciple of guru Murshida Ivy Duce, “Snow Beneath the Belly of a White Swan: The Lost Live Recordings” captures Basho in concert for the first time, a setting in which he truly stretched his wings.

“He seemed like someone who wasn’t entirely comfortable in his own skin,” said Tompkins Square owner Josh Rosenthal. “A studio setting was a little limiting and claustrophobic for him, and the Basho you hear on these tapes seems a little more expressive and expansive. He’s out there doing a high-wire act live. You get a different vibe listening these pieces.”

Released on Dec. 6, the live recordings also significantly expand Basho’s repertoire, with half a dozen previously unknown tunes. He even interprets two pieces by John Fahey, a fellow American primitive steel-string explorer who launched the movement with the 1966 album “Contemporary Guitar.” The compilation introduced Fahey’s influential Berkeley-based Takoma Records with tracks by himself, Basho, rediscovered Delta bluesman Bukka White, Max Ochs, and Harry Taussig.

Whatever company he kept, Basho stood out as a singular artist. Barker’s deeply researched liner notes offer a fascinating ground-level view of the guitarist at work, with a particular focus on the challenges and economics of concertizing. A review in the Oshkosh Daily Northwestern finds that the guitarist “could not reconcile a total perfectionism with the needs of the crowd. People got up and left throughout the performance as Basho spent more time tuning his guitars than playing them.”

Barker was able to identify the origins of some tapes, with material recorded at the Berkeley folk coffeehouse Jabberwock in early 1966 and Saratoga’s Paul Masson Mountain Vineyard, where Basho opened for the great blues duo Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee in the fall of ’73. “Himalayan Highlands” was recorded May 13th, 1967 at UC Santa Cruz’s Cowell College. But the condition of many of the reels made dating them impossible. Simply recovering the music was something of a miracle.

“It was a complicated process,” Barker said on a recent video call from the U.K. “I went to this individual’s house, a chaotic place with filth everywhere and thought there was no chance these tapes will survive. Most of the tapes weren’t labeled. We included all the information we had about where the music was recorded.”

Though much of the music is undated it provides a fascinating if somewhat opaque view of Basho’s evolution, a process guided by his intense spirituality. Initially inspired by North Indian classical music, his approach to the 12-string steel guitar continued to evolve, absorbing a far-flung array of sounds from Native American and Japanese sources.

Born Daniel Robinson Jr., he adopted Basho in honor of the 17th-century Japanese poet Matsuo Bashō, a master of haiku. Concision, however, was not part of the guitarist’s forte. He always seemed to think big.

“He’s incorporating 20th century classical influences,” Rosenthal said. “It’s a ‘Performance’ and every time it’s worthy of being on stage at Carnegie Hall, even if he might be playing a dump.”

Contact Andrew Gilbert at jazzscribe@aol.com.