Developers who have reaped millions of dollars from an affordable housing program for middle-income renters with sometimes little-to-no discounts from market rents have spent hundreds of thousands on lobbying and campaign donations in recent years in a bid to keep lawmakers from imposing regulations.

Related Articles

Are California real estate markets warped by sober homes paying top dollar?

Bay Area remembers former President Jimmy Carter

Can’t afford to buy a home solo? This Bay Area company wants to help friends buy real estate together

Being a ‘bedroom community’ comes at a cost for those south of Silicon Valley

California has 15 of 25 priciest places to live in US

The expenditures represent a fraction of the $32 million the California real estate industry as a whole spent on lobbying the state legislature and the executive branch in the past three years. But they helped the industry stop a bill seen as a threat to their business model, in which state-established finance authorities issue bonds to buy property to turn into income-restricted housing, and private developers collect fees from brokering the deals. Because they’re owned by a public agency, the buildings are exempt from property taxes, the savings from which are, theoretically, used to set rents at lower levels.

Since 2021, two developers of these projects, Catalyst Housing of Larkspur and Waterford Property Co. of Newport Beach, have spent $610,000 on lobbying legislators and government officials about the value of their “essential housing” strategy in addressing California’s affordable housing shortage and how it could be harmed by regulation that would have capped how much rent they could charge.

Those two developers, and a handful of other essential housing players, have also spent $282,000 in donations to state politicians in key positions to block regulation or help them clear hurdles established by local authorities.

“Those profiting from these transactions were unwilling to accept any meaningful accountability requirements, including that rents be discounted meaningfully from general market rents,” said Mark Stivers, director of advocacy for the California Housing Partnership, one of the program’s critics. “Greater accountability to the public is still very much needed.”

Developers of middle-income housing said they feared over-regulation would strangle a useful tool to build income-restricted housing that doesn’t rely on federal subsidies to provide rental discounts. California has struggled to develop more affordable housing, with officials setting a target of 2.5 million new units before 2032, including 421,251 specifically for moderate-income households.

“What we didn’t want to have happen was to have the program get killed because of the guardrails,” said Sean Rawson, co-founder of Waterford, a company with a portfolio of 13 essential housing projects in Southern California and one of the first to take advantage of the program.

Developers, including Waterford and Catalyst Housing, have brokered $8 billion in essential housing deals since 2019. They laud the program as an innovative way to provide housing for middle-income renters who make too much to qualify for federally subsidized, low-income tax-credit housing but may struggle to afford market-rate rents.

But the rents the developers charge also don’t abide by the same strict regulations as federally subsidized affordable housing. About half of the units at the 13 Northern California essential housing properties charge higher rents than comparable nearby market-rate buildings, the Bay Area News Group previously reported.

Meanwhile, for the 3,401 units across those properties, developers have collected $25 million in upfront fees and stand to make millions more in interest payments over the 30- to 40-year lifetime of the bonds. Another $48 million in fees has gone to the bankers and law firms that issue the bonds. Meanwhile, cities forfeit an annual $21 million in property taxes to support the program, though each city is meant to recoup property taxes lost at the end of the bond’s term, as the agency gives them an option to purchase or sell the property.

In 2022, the legislature proposed regulating these deals to ensure the rent discounts would be commensurate with the tax benefits the program received. Working with the California Housing Partnership, Assemblyman Chris Ward, a San Diego Democrat, introduced a bill, AB 1850, to establish stricter affordability standards and cap developers’ fees on the essential housing deals — what he hoped would prevent “abuse” by some for-profit players that “snookered” cities into giving up property taxes without delivering on middle-income housing promised.

Waterford and Catalyst hired top lobbyists to fight the bill — Catalyst Housing spent $186,565 to hire lobbyists at Actum, and Waterford spent $135,000 to hire lobbyists at Axiom Advisors, including Jason Kinney, a friend of Gov. Gavin Newsom, who attended an infamous 2020 dinner party at the French Laundry with the governor despite pandemic-era restrictions.

Rawson crafted a compromise bill that included some rental restrictions but still would allow the projects to generate enough revenue to justify his company’s investment. Waterford’s projects in Southern California, he said, have managed to provide a 19% discount to market rate without extra regulation.

“As drafted originally, the bill was going to make projects financially unfeasible,” Rawson said of AB 1850. “In a public-private partnership, you have to have an incentive.”

When asked for comment on its lobbying and whether it would have accepted any regulation, Catalyst spokesperson Stefan Friedman said in a statement that “historic housing policy and traditional production methods are not working” and that Catalyst was “proud to fight that status quo and support housing leaders who do the same.”

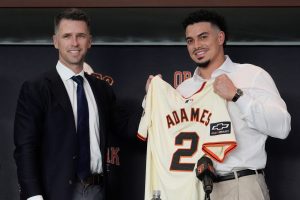

Waterford Property Co. co-founders Sean Rawson, left, and John Drachman in Long Bach. (Mel Melcon/Los Angeles Times/TNS)

As AB 1850 went to the Senate Governance and Finance Committee for a second hearing, two votes were in play: Majority Leader Bob Hertzberg, D-Van Nuys, and Sen. Anna Caballero, D-Merced, the committee’s chair. With Hertzberg not voting, Caballero cast the deciding vote that killed the bill.

Four months later, Caballero’s reelection campaign received $4,000 from a group that had never donated to her before: Waterford. In March 2023, they donated another $4,000.

Caballero’s office declined to comment, but at the hearing she said, “We desperately need housing, and any tool in our toolbox that provides us with an opportunity to do that is really important. … Whenever there are two sides that are absolutely opposed, and there’s a sweet spot in the middle, it’s important to me to understand where that sweet spot is.”

Some critics of the essential housing model say the industry has used donations to curry favor with key legislators, allowing them to introduce and pass bills favorable to the industry or ensure hostile ones don’t advance.

But there are limits to that influence. In 2023, for example, essential housing came under a new threat when a county tax assessor in Southern California argued that moderate-income housing didn’t qualify for a property tax exemption and used an obscure provision of tax law to start billing Waterford, as well as some tenants, for taxes. Waterford fought back, saying that neither the company nor its tenants should foot the bill. If Waterford is forced to pay taxes, the company said, it will eat at the company’s profits to the point where the projects would be unfeasible.

Assemblyman Josh Lowenthal, a Democrat from Waterford’s home district in Long Beach who has received $50,000 from Waterford’s founders and their partners in campaign donations, introduced AB 2506, a bill to stop county assessors from charging tenants these taxes. A spokesperson for Lowenthal said in a statement that Waterford “was one of many stakeholders involved in discussions on this program,” among housing advocacy groups, tenants and county assessors.

Lowenthal later pulled the bill after it stalled in a committee where staff were highly critical of the precedent it would set. His spokesman said he doesn’t have plans to reintroduce it this year.

Among the essential housing players, Waterford has been the most prolific donor, giving $152,863 in donations over the last three years to legislators in key positions, including Senate Majority Leader Lena Gonzalez and Assembly Minority Leader James Gallagher. Gonzalez and Gallagher did not respond to a request for comment.

Waterford and other essential housing developers have also given $101,950 in that time period to State Treasurer Fiona Ma, who sits on a board that allocates highly competitive state tax credits for traditional subsidized affordable housing development, which many developers involved in the essential housing program also build. Through a spokesperson, Ma’s office said, “Political contributions have no bearing on policy decisions or any aspect of the committee’s decision-making process.”

Rawson said that his company supports “good housing policy in general in California” and is proud to partner with both local and state leaders to build more housing for middle-income earners through the essential housing program.

“It’s not the perfect fix for middle-income housing, but it’s the best program out there,” he said. “What other programs exist in California to provide that type of housing? There’s none.”