Concord is one step closer to rezoning a fraction of its higher-income, predominantly white neighborhoods — a change that will enable development of 1,000 new lower-income, multifamily units in areas boasting access to schools, parks, jobs and transportation by 2031.

The city has spent months exploring the feasibility of its Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing (AFFH) rezoning project, which will create a 20-acre zoning overlay district in Concord where developers and property owners can construct up to 60 units per acre of high-density housing, in addition to existing land uses.

This self-imposed 1,000-unit benchmark was set in stone nearly two years ago as part of Concord’s Housing Element. Certified by the state’s Department of Housing and Community Development (HCD) in October 2023, that 1,100-page document outlines the city’s eight-year plan to successfully approve 5,073 new units — more than half of which must be earmarked for affordable to low- and middle-income residents.

The city’s AFFH project stems from AB 688, which state legislators passed in 2018 to address racial, ethnic and economic disparities in local housing policy. Expand the federal Civil Rights Act of 1968, the law mandated all cities in California to incorporate meaningful updates to their housing policies “that overcome patterns of segregation and foster inclusive communities free from barriers that restrict access to opportunity based on protected characteristics.”

Justin Ezell, Concord’s assistant city manager, said “upzoning” — modifying land use rules in specific areas to allow for multi-family homes and other high-density development — has been “one of the primary strategies” for local leaders in cities like Pleasant Hill, Walnut Creek, Milpitas and Berkeley that have long struggled to facilitate construction in wealthier neighborhoods and bolster housing mobility.

Related Articles

Workforce housing real estate firm buys San Jose apartment complex

Oakland housing highrise is bought in deal that hints at wobbly market

A look at the progress of construction behind the wall of containers at People’s Park

Which way will mortgage rates go in 2025?

Bay Area offices, hotels and apartments falter, but tech deals offer hope

To ensure an effective AFFH project, Concord staff analyzed areas of affluence and influence in the increasingly diverse city — excluding sites featuring protected open spaces, single family homes, moderate or low access to amenities or other problematic barriers. Eventually, a map of 7,000 parcels – roughly a third of the city’s entire land area – was whittled down to a list of 25 locations for community consideration.

On Tuesday, the Concord City Council unanimously agreed to focus on seven different sites, largely concentrated within the southeastern corner of the city. Planners will now start the laborious environmental review process, studying how the proposed AFFH zoning changes could impact schools, roadways, ecosystems and communities near those properties.

At the top of that short list is the 90,000-square-foot Kmart building on Clayton Road, which has remained virtually vacant since it shuttered in February 2020.

That roughly 8-acre site, excluding the adjacent shopping center, is currently zoned for up to 24 residential units per acre. If Concord officials move forward with the AFFH plan as-is, the proposed zoning overlay would allow a maximum of 471 homes there – a 150% increase from the current 188 cap. Similar expansions are eyed for Clayton Faire, a popular commercial hub where Kirker Pass Road turns into Ygnacio Valley Road, which could support up to 250 residential units. Additionally, a 13-acre infill site near Palm Lake Apartment Homes could sustain roughly 475 additional homes off Treat Boulevard and Oak Grove Road.

For scale, a housing complex with 24 units per acre is typically 2 to 3 stories tall. Based on guidance from HCD, projects that maximize the program’s expanded regulations – 60 units per acre – will exceed six stories.

Councilmember Dominic Aliano suggested a plan that analyzed as many different options as possible — allowing the city to map out a configuration that can realistically achieve its state-mandated goals.

“Right now, we’re in a position where we really don’t know everything – we need to find out how this is really going to impact each specific community,” Aliano said during Tuesday’s council meeting, cautioning the city against “opening a can of worms for HCD to look into” with any other, supplemental zoning modifications that may not conform to state law. “It’s our responsibility to protect the quality of life for people within our community. The fact is, not everyone’s going to be happy with any decision we make.”

Eric Yerkovich, a principal with lead consultant Raimi + Associates, said that the patterns of segregation within Concord’s boundaries are in lock step with communities across California.

He said the Monument and North Concord neighborhoods, which face some of the city’s highest poverty rates, reported some of the biggest disparities in terms of economics, race, upward mobility and fair housing access. Conversely, high concentrations of affluent residents live in the southern and eastern portions of Concord — a region that boasts stronger economic, educational and environmental outcomes.

“As home prices have become more expensive — not just here within Concord, not just in the East Bay, but across the entire state,” Yerkovich said, “it’s been more complicated for lower income families to find housing across the city, and, in particular, high resource areas.”

The next phase of the city’s AFFH project will be a months-long slog.

Environmental impact reports are expected to be completed by Summer 2025, which the Concord Planning Commission and City Council will later review for final approvals towards the end of 2025 — several months behind schedule, according to city staff.

On paper, the AFFH’s plan could account for a fifth of Concord’s statewide housing obligations.

There’s no guarantee, however, that a new overlay zoning will actually spark high-density development as intended, and questions still linger about what types of blueprints will actually be viable to build.

Vice Mayor Laura Nakamura was concerned that lower density projects may be better suited for the current construction and labor markets, citing the city’s recent feasibility analysis during Tuesday’s five-hour joint council and planning commission meeting.

Compared to Concord’s current plan for 60 units per acre, Nakamura said, “the implications of what we’re doing (with the AFFH project) is very different.”

Similarly, Planning Commissioner Jason Laub was one of the officials who mulled over ways to meet the city’s 1,000-unit goal while still keeping individual project densities low within the zoning overlay.

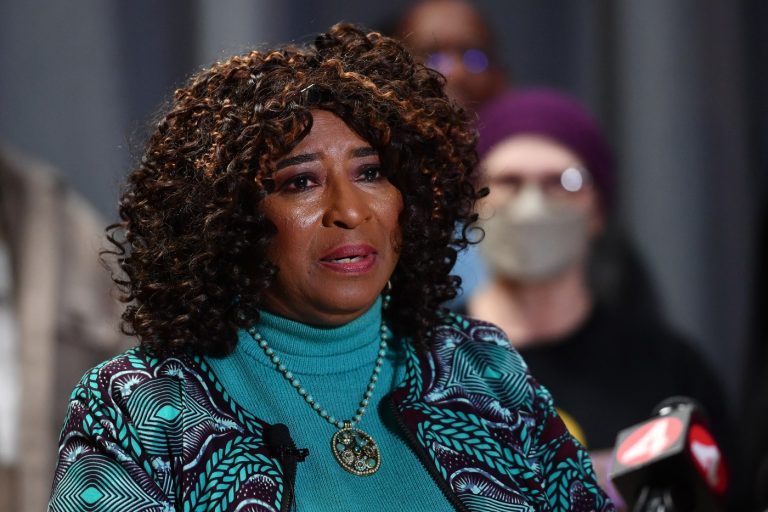

But City Manager Valerie Barone said “it seems quite likely the state will look unkindly on the approach,” based on ongoing conversations with state housing officials while crafting the Concord’s Housing Element and AFFH policy language.

“The state’s given you, to some degree, a limited deck with which you get to play with,” Barone said Tuesday. “We’re trying to find the best route through, given those constraints.”