California’s public schools, with nearly 6 million students, are feeling the financial impacts of a quintuple whammy.

Billions of federal dollars to cushion the impacts of COVID-19 have been exhausted, school closures during the pandemic magnified declines in enrollment, chronic absenteeism has worsened, inflation is increasing operating costs, and the state budget is plagued by a huge deficit.

Since the state largely finances schools based on their attendance, many local districts are seeing ever-widening gaps between income and outgo, stalling what had been a decade-long pattern of increasing per pupil spending.

Local school trustees have few options to balance their budgets. They can close schools with low enrollments, lay off teachers and other staff or ask voters to approve tax increases, usually what are called “parcel taxes” on homes and commercial property — all of which encounter resistance.

There is one other way for school officials to reduce their financial gaps: make it more difficult for charter schools to operate.

Charter schools also get their money from the state, but operate independently. For years, they have been engaged in a running battle with school unions, particularly those of teachers, which contend that they undermine regular public schools by siphoning away students and money.

As overall school finances are squeezed by the phalanx of interrelated issues, the battle over charter schools is becoming more intense. Earlier this year, after union-backed candidates achieved a majority on the board that governs the state’s largest school district, Los Angeles Unified, it cracked down on housing charter schools within traditional schools.

LA Unified now bars charters from sharing space in schools considered to be serving vulnerable students, affecting more than a third of LAUSD’s 850 campuses. Its immediate effect was to force about 21 charter schools to find new quarters.

This month, an even more direct assault on the charter school movement surfaced in the Legislature when the Senate Education Committee approved legislation, backed by the California School Boards Association and school unions, that would make it more difficult for new charter schools to gain approval.

Current law, enacted three decades ago, basically favors the creation of charter schools unless an affected school district can prove that it would be economically devastating or is already in receivership due to financial problems.

Senate Bill 1380 would expand the ability of school districts to claim financial hardship as a reason for rejecting charter applications within their districts. It would also effectively repeal a current law allowing charters rejected by a district to seek approval by a county board of education.

The measure is being carried by Sen. Bill Dodd, a Napa Democrat, and stems in part from a local charter school conflict. But it would have statewide impacts, making it markedly more difficult for new charter schools to gain approval.

“When it comes to educating our children, locally elected school boards must decide how our precious resources are spent,” Dodd said in statement. “They must have the tools to recover from financial setbacks due to declining enrollment and focus their funds where they will have the greatest benefit.”

Related Articles

Opinion: How California’s ‘math wars’ are hurting Black and Latino students

Letters: No pressure | Competition’s benefits | Special election | Loss of privacy | CPUC choice | Business tax

Federal review slams California school district’s failures to address sexual abuse complaints by students

Fremont Union School District approves district zoning map for new trustee election system

California schools may be required to provide kosher and halal meals

Charter schools opposed the bill during the Education Committee hearing, complaining that it would add even more restrictions on formation of new charters than those imposed in a 2019 bill also supported by unions.

Whatever the effect SB 1830 might have on the finances of local school districts, their fundamental problems of declining enrollment and attendance will continue.

The Public Policy Institute of California, in a recent report, says enrollment declines “are expected to continue, with the state projecting a decline of over a half million students by 2031–32 (while) federal projections suggest nearly a million.”

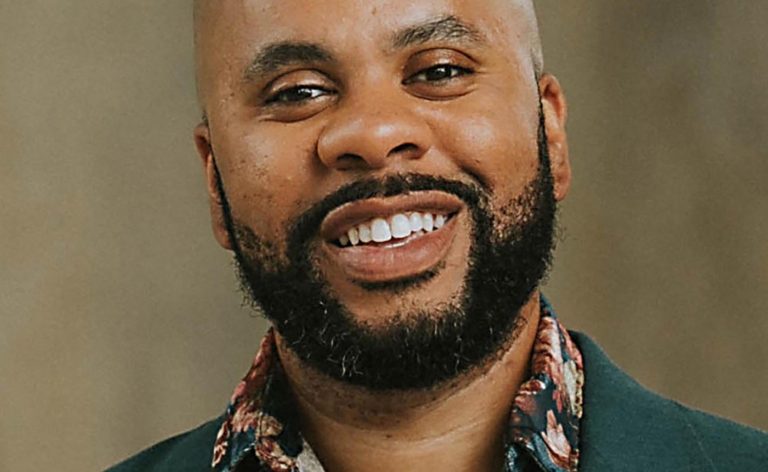

Dan Walters is a CalMatters columnist.