Nearly 80,000 educators in dozens of school districts across the state joined forces Tuesday to launch an unprecedented campaign for better wages.

Educators in San Jose, Oakland, San Francisco, Berkeley, Hayward and West Contra Costa County joined 32 school districts across the state to demand higher wages and benefits, fully staffed schools and safe campuses in what the California Teachers Association dubbed the “We Can’t Wait Campaign.”

David Goldberg, the president of the California Teachers Association, pointed out that California ranks in the bottom half of states for pupil spending and 48th in the nation for access to school counselors, despite being the fifth largest economy in the world.

“We are facing a crisis in our public schools. There are not enough educators on our school campuses,” Goldberg said. “The resources we do have are constantly under attack and threats of cuts…So if we don’t act now on behalf of California students (and) educators in school, when will the time be right? We can’t wait any longer.”

But educators’ demands come at a precarious moment in public education. California students continue to trail their peers across the nation in reading and math, executive orders from the Trump administration are causing panic among immigrant communities and leading to drops in student attendance and districts strapped for cash are being forced to consider school closures and steep budget cuts.

Lance Christensen, president of business advocacy group California Policy Partners, who lost an election to state Superintendent of Public Instruction Tony Thurmond, said the timing of educators’ demands for higher wages is “not only unreasonable” but also not “self-reflective.”

“When less than 40% of our kids are at grade-level proficiency in math and English language arts, it makes me wonder what the unions are trying to advocate for in terms of better benefits and salaries. I think they have it backwards,” Christensen said. “Most districts’ budgets are anywhere from 91% to 93% personnel costs, which a huge amount of those are teachers salaries and pensions and benefits.”

But the California Teachers Association argues that not only do educators in the state struggle to pay rent and make ends meet, they’re also vastly underpaid as a field.

Sylvia Allegretto, a senior economist at the nonpartisan think tank Center for Economic and Policy Research, estimates the average weekly wage for California public school teachers in 2022 was $1,844, while other college graduates received an average weekly wage of $2,847.

California teachers’ salaries are determined by experience and education level. The average salary of a public school teacher for the 2021-22 school year was $88,508 and $95,160 for the 2022-23 school year – the highest in the nation.

But Allegretto said that while teachers in California and New York are often paid more than teachers in Alabama and Mississippi, that doesn’t account for the cost of living difference in those states.

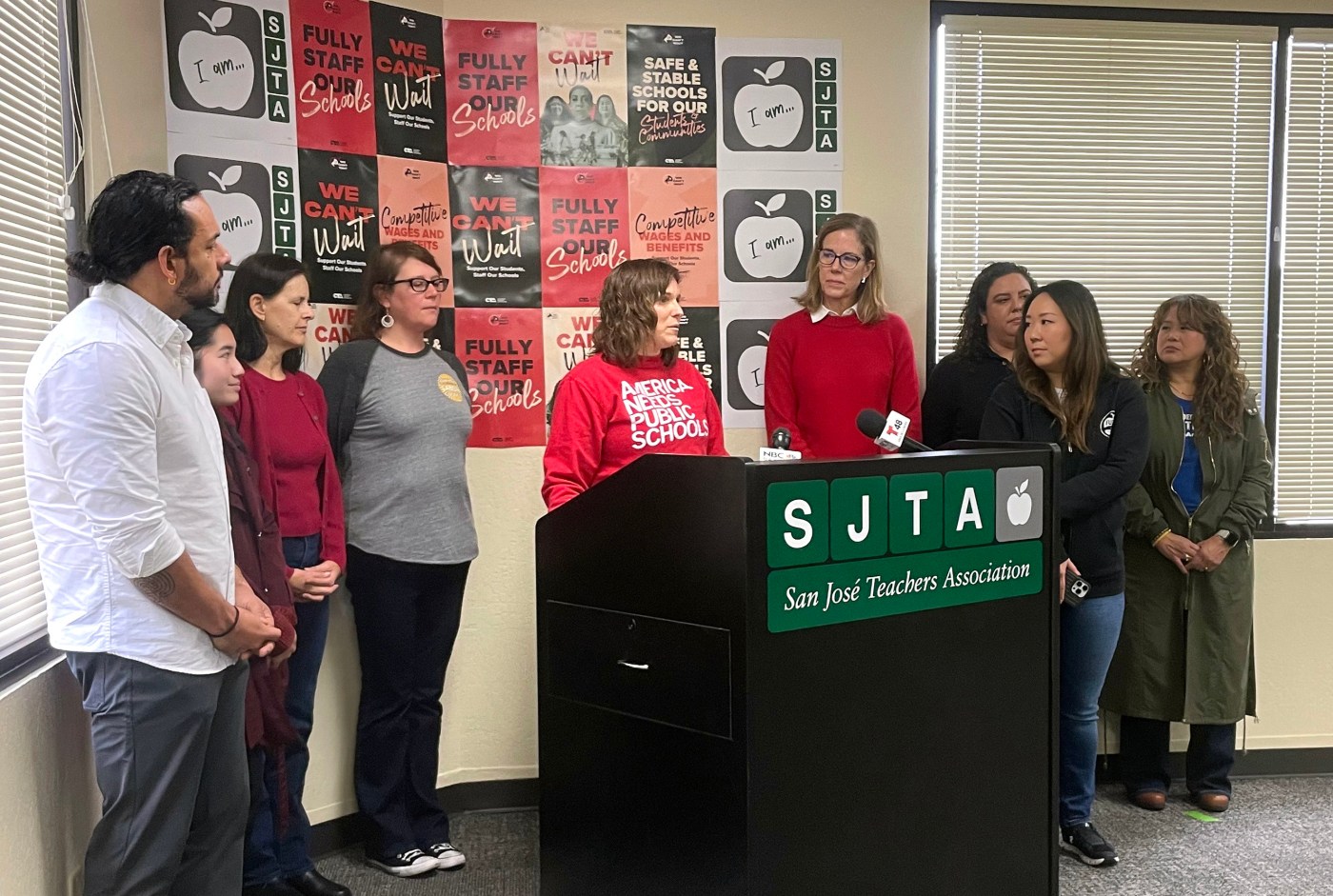

San Jose Teachers Association president Renata Sanchez said the high cost of living in the Bay Area forces many educators to work multiple jobs in order to live in the communities where they teach.

“My mom taught for 37 years. She was able to purchase a home and comfortably raise a family of five on a teacher’s salary,” Sanchez said. “I’ve been teaching for 17 years and I cannot afford rent for a single-bedroom apartment by myself without commuting for hours away each day…The educator wage gap is wider than it has ever been.”

In November, San Jose voters approved a $1.15 billion bond measure – Measure R – that will be used to upgrade school facilities and provide employee housing. Four different housing sites are estimated to provide more than 600 rental units ranging from $650 a month to $900 a month, according to the San Jose Teachers Association, well below market rate.

San Jose Unified School District did not immediately respond to this news organization’s request for comment.

The ongoing impacts of declining enrollment and the end of pandemic funding for districts across the state have also led some to wonder if schools even have the funds needed to boost educators’ salaries.

Sanchez acknowledged the concern that school districts don’t have the money to provide the resources that students need.

“We know that the problems that we’re trying to solve, we can’t solve alone at our tables, because each individual school district is doing the best that they can,” she said. “We need the state to come in and provide more support to the schools and our school districts so that they do have that adequate funding.”

Related Articles

Sunnyvale: High school briefly placed on lockdown while police investigate gunshot nearby

California superintendent Tony Thurmond sends note to schools about Title IX protections

West Valley school district makes interim superintendent permanent

Opinion: AI is harming our children. California must step up

California schools could warn students, parents if ICE agents show up, new bill proposes

Oakland Unified is one district facing intense financial strain. The district is projected to run out of cash during the 2025-26 school year without significant intervention and has said it plans to consolidate up to 10 schools.

But Kampala Taiz-Rancifer, president of the Oakland Education Association, the teachers union, said the district does have the necessary resources to keep schools open and that it’s a matter of priorities.

“For many years, a systematic disinvestment in Oakland schools has really adversely impacted the quality and therefore enrollment in Oakland schools,” Taiz-Rancifer said. “Oakland educators joined this fight because we can’t wait any longer to create the stability that we need to improve outcomes for students.”

Oakland Unified School District did not immediately respond to this news organization’s request for comment.