In the next year, San Jose will bring online over 1,000 new quick-build housing units and shelter beds for the homeless.

The taxpayers of San Jose are meeting their responsibility to our unhoused neighbors. It’s time to require through enforcement that our homeless neighbors meet their responsibility to the wider community.

Increasingly, we see people refusing shelter when it is available. That’s because the more people we bring indoors who want shelter, the more likely we are to encounter the subset of people who are “service resistant” — unwilling to come indoors due to an addiction, mental health issue or personal preference. Recently, over 30% of the inhabitants of an encampment along Great Oaks Boulevard refused new individual interim housing units with private bathrooms and kitchenettes — a trend we’re seeing across several new sites.

It isn’t just refusing shelter that is at issue. While most homeless people strive to be good neighbors, not all are showing basic respect for their communities. San Jose spends tens of millions of dollars each year responding to fires in encampments, moving people from one street to another, removing illegally dumped garbage from our waterways, picking up human waste and used needles in public spaces, and much more.

If a housed resident dumped garbage in the street in plain view, they would be fined. If a housed resident parked a vehicle for too long on their neighborhood street, they would receive a ticket. If a housed resident of San Jose set a dangerous fire, they would be fined or even jailed.

We should hold everyone in San Jose accountable to the same basic code of conduct. And that starts with requiring homeless neighbors to come indoors.

That’s why I am proposing that our city embrace enforcement as a necessary tool for achieving our goal of moving everyone indoors. To do so, we need to update city policy to enforce trespassing laws against those who repeatedly refuse shelter. Enforcement should progressively escalate from warnings to citations to ultimate arrest for repeat violations of our municipal code, including refusing shelter, tapping city electrical lines and camping in no-camping zones.

Even brief incarceration is an action we should not take lightly. However, if an individual is repeatedly unable or unwilling to accept a safe space with supportive services, the city has used all the tools we have available. At this stage, we have a responsibility to get people into the care of the county. There the magistrates who oversee our behavioral health courts can determine a better path forward and interrupt the cycles that are keeping people on the streets.

Related Articles

Should San Jose homeless be charged with trespassing for refusing shelter?

Fremont walks back controversial ‘aiding and abetting’ clause in recent camping ban

He died alone on a Bay Area street. Could these new treatment reforms have saved him?

She was arrested for sleeping outside while homeless. Now, this Bay Area resident is headed to trial

‘A volunteer jail:’ Inside the scandals and abuse pushing California’s homeless out of shelters

Leaving people to live and — over 200 times each year in our county — die on our streets, often when they are too deep in the throes of addiction or mental health crisis to make a rational decision about their own self-care, is neither humane, progressive nor practical.

And while we want to use incarceration sparingly, since the passage of Proposition 36, we now can use an interaction with the criminal justice system as an impetus for requiring drug and alcohol treatment for the addictions that drive so many people into homelessness and keep them there.

Ending street homelessness requires holding the city, nonprofit partners, the county and the state accountable for results. But accountability is a two-way street. It’s time we also hold our homeless neighbors accountable for refusing shelter or not being good neighbors. Because in San Jose, homelessness should never be a choice.

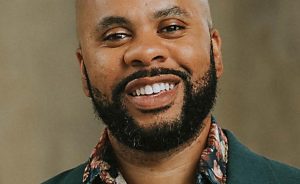

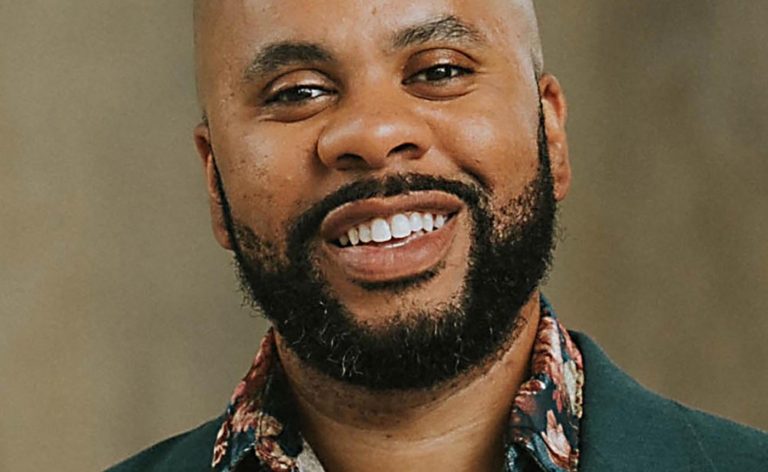

Matt Mahan is the mayor of San Jose.