CONCORD — For the past decade, Schneider Electric has wooed educators across the country with promises of green, cost-cutting energy solutions to help improve learning conditions inside school halls and classrooms.

Whether modernizing heating and cooling equipment, lighting fixtures or building control systems, the Texas-based multinational company has boasted that its services not only reduce energy consumption, but also save school districts money in the long run.

But several watchdogs responsible for ensuring effective spending of taxpayers’ dollars are now ringing alarm bells over one multi-million-dollar Schneider Electric project in Contra Costa County. Complaints have snowballed into questions about whether the Mt. Diablo Unified School District illegally allowed Schneider to scope, design and construct energy-efficient improvements to buildings district-wide, ultimately doubling their cost to $50 million.

What’s more, an oversight committee is claiming that the district is stonewalling its attempts to investigate this contract, perhaps in violation of California law.

The school district’s Citizen’s Bond Oversight Committee (CBOC) on Thursday discussed sending a formal letter in June to the county’s civil grand jury about its concerns, shortly after sharing the same grievances with District Attorney Diana Becton’s office.

Committee members — who are appointed by MDUSD’s governing board — are looking into allegations related to Schneider Electric’s “energy savings performance” contract with the district. Similar contracts at the crux of Schneider’s pitch to educators have been clouded by allegations of malfeasance, including criminal forfeiture of $1.7 million and a $9.3 million settlement in Dec. 2020 involving at least eight projects with the federal government.

Under current regulations, contracts classified as “energy savings performance” can be approved without being put out to competitive bidding, as long as the amount of money saved from efficiency upgrades exceeds project costs. The district took Schneider at its word that the projected savings will surpass $37.7 million within 20 years; in fact, the contract stipulated that the company’s data on projected savings would be approved without any additional measurement or verification.

Concerns that the school board has not properly handled these allegations have gotten so serious that the oversight committee has tentatively suggested starting a campaign to recall MDUSD’s board trustees, who approved the contract and subsequent revisions with Schneider.

Jack Weir, a member of the oversight committee, has spent two decades doing similar work on over $1 billion in school bonds for six different oversight committees. He said at a March 7 committee meeting that, “we would prefer the district to clean this up if there is a problem. But from my perspective, we aren’t getting any cooperation back from the (school) board, and this has gone on for months, and months, and months.”

Gina Haynes, the oversight committee’s chair, said reaching out to the county’s district attorney — and potentially a civil grand jury down the line — was a last resort, after school district Superintendent Adam Clark and the board denied the committee’s request for $14,250 to hire independent legal counsel to review allegations of possible wrongdoing.

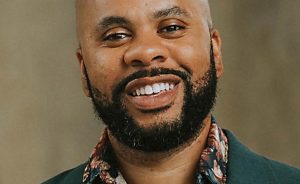

At-Large Community Member chairperson Gina Haynes, left, and Taxpayer’s Association member Jack Weir attend the Citizen’s Bond Oversight Committee meeting held at the Mt. Diablo Unified School District office in Concord, Calif., on Thursday, May 16, 2024. (Jose Carlos Fajardo/Bay Area News Group)

“I just want to know, did we do it wrong? And learn from it,” Haynes said Thursday, adding that the oversight board has asked for independent legal help on this issue for more than a year. “I applied for this committee — I’m not here just to rubber stamp. My job is to report out to the public, and I feel like I can’t do that.”

MDUSD Superintendent Adam Clark defended the project’s legality and completion, arguing that the CBOC’s repeated requests and complaints about the bidding process and energy savings of Schneider’s project are “clearly outside of their scope of responsibility.” After the committee was not satisfied with Schneider’s answers over several meetings, he said that the CBOC also refused to use the list of attorneys — and narrower scope of investigation — that the district offered.

“The role of the CBOC is — after a project is complete — to basically verify that we did what we said we would do,” Clark said Friday. “Of course, if something’s amiss, I want to get to the bottom of it. My concern is if we start hiring attorneys on their behalf and keep going down different rabbit holes, that’s not very responsible and not even how we do business.”

Potential trouble began brewing in March 2023, when the total project cost swelled to $49.4 million after the school board unanimously approved an amendment to Schneider’s May 2022 contract to replace lighting fixtures and ceiling tiles district-wide. The expanded scope included nearly $25.1 million of additional work on heating and cooling systems, which was not separately put out to bid.

Schneider has signed similar contracts with several other school districts nationwide, including Northern California projects in Berkeley, Dublin, Dixon and Stockton.

But state officials have advised other government officials for years that this no-bid-extension process may violate state laws regarding conflicts of interest.

In addition to a letter sent in 2019 to the city of Pleasanton, California’s Fair Political Practices Commission also advised the city of Concord’s legal team in 2020 about this same concern.

Marc Starkey, an account executive for Schneider Electric who has managed over $150 million in school district projects for the company, including the Mt. Diablo district, refused to comment on the accusations or respond directly to the oversight group’s push to investigate the contracting issues. However, he said he believes the a new state law, which went into effect in January, ensures that their two-step contracting process is “completely legal.”

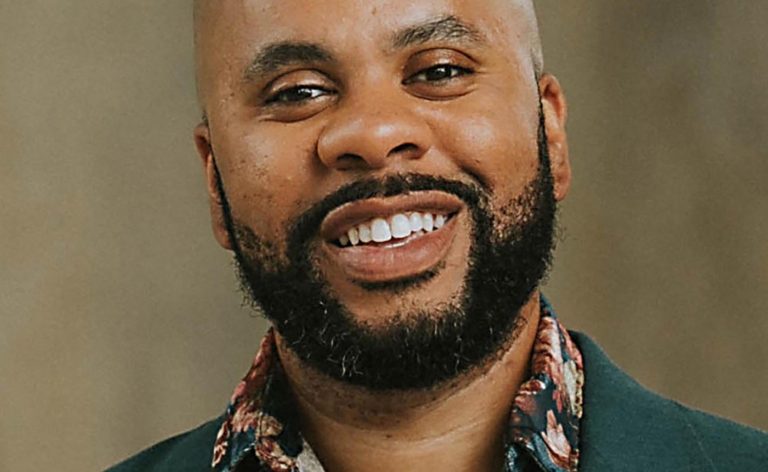

Schneider Electric account executive team leader Marc Starkey attends the Citizen’s Bond Oversight Committee meeting held at the Mt. Diablo Unified School District office in Concord, Calif., on Thursday, May 16, 2024. (Jose Carlos Fajardo/Bay Area News Group)

“This hasn’t been brought up in like 200 of our contracts that we’ve done over the last 15 years, so it hasn’t been an issue,” Starkey said Thursday. “The committee’s here to make sure that district’s performing right, so they have every right to do that. But we’re going to respond to how the district wants us to — we’re going to be here every step of the way.”

In 2018, voters approved Measure J, a $150 million school bond bookmarked for campus infrastructure improvements and energy system efficiency upgrades. According to flyers ahead of the election, more than 85% of polled voters shared four top priorities for that money, which is paid back by increased property taxes: improvements to technology and science in classrooms, building repairs to aging roofs, plumbing and electrical, campus security measures and upgraded computers and engineering classrooms.

However, Schneider’s heating and cooling work, and lighting work has already accounted for more than 60% of the total $46 million spent on Measure J projects by the end of March, according to a quarterly report the oversight committee released this month. Those records also show that the district still owes another $20.3 million for the company’s contract.

Haynes, the committee chair, said this discrepancy between funded projects and the district’s $1 billion “wish list” of priorities provides “a little snapshot of what we really need to upgrade at all these school sites. If we could have gotten all this work done for half the price, we wouldn’t want to make this mistake again.”

Schneider’s federal settlement from 2020 echoes the Mt. Diablo Unified School Board’s bond oversight committee’s current concerns about doing the right thing, and learning from past mistakes.

“Ever since we brought this up and wanted to investigate, there’s been all this pushback, especially from the superintendent,” Haynes said, adding that she’s uncomfortable with how contentious meetings have become. “We’re volunteers who are just trying to do oversight. It shouldn’t be this hard.”